Early years

When William Moss was born on 17 May 1843 at China Row in Stratford, his parents,

George and Eleanor Moss (née Evans), had been living on the Essex side of the River

Lea for about four years. China Row was a row of wooden-fronted buildings so named because of their proximity to the famous Bow China Works which, although closed for

some 60 years by 1843, had been sited on the Essex side of the River Lea by the Bow

Bridge. This was just one of the early industries that had grown up around the River

Lea. However, it was in the nineteenth century that industrialisation really took

over, and not entirely to Stratford’s advantage. The 1844 Metropolitan Building Act

severely limited many toxic and noxious industries from operating in London and Middlesex.

As a result, many of these processes were moved across the Essex border to Stratford

and West Ham. Industries included rendering animal carcasses for tallow, soap and

glue, chemical plants for acids, pharmaceuticals or printing inks. The blend of ‘aromas’

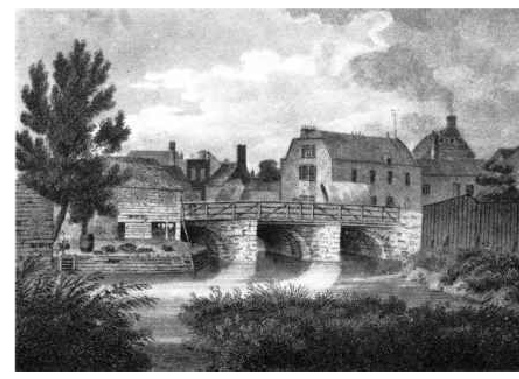

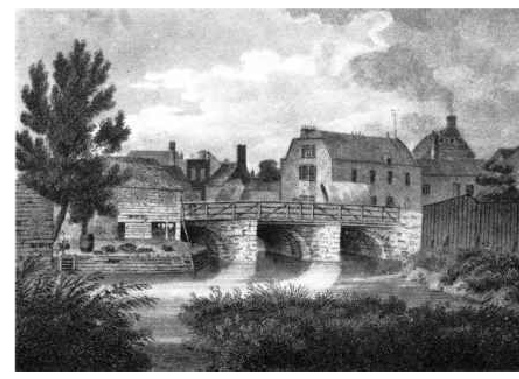

would have delivered a constant affront to the nostrils. (The illustration above

shows the old Bow Bridge in 1837).

because of their proximity to the famous Bow China Works which, although closed for

some 60 years by 1843, had been sited on the Essex side of the River Lea by the Bow

Bridge. This was just one of the early industries that had grown up around the River

Lea. However, it was in the nineteenth century that industrialisation really took

over, and not entirely to Stratford’s advantage. The 1844 Metropolitan Building Act

severely limited many toxic and noxious industries from operating in London and Middlesex.

As a result, many of these processes were moved across the Essex border to Stratford

and West Ham. Industries included rendering animal carcasses for tallow, soap and

glue, chemical plants for acids, pharmaceuticals or printing inks. The blend of ‘aromas’

would have delivered a constant affront to the nostrils. (The illustration above

shows the old Bow Bridge in 1837).

Twice bound

Life was a struggle financially for William’s parents, although it is likely that

William attended school for a few years, probably until about the age of ten, certainly

in 1851 he was described as a ‘scholar’. By the mid 1850s, William’s thoughts were

turning to work. Both his parents were skilled tailors, but from the mid-1840s tailoring

no longer offered a good living or steady employment; those who mastered the technique

required to operate the new mechanised sewing machine could earn 16s a week, but

this work was generally carried out by women; the industry was also changing with

the introduction of ‘slop’ labour undertaken by women and girls in their homes.  William’s

father also died in the 1850s, putting more financial strain on the family’s meagre

resources, but freeing William from any obligation to follow in his father’s footsteps.

William’s

father also died in the 1850s, putting more financial strain on the family’s meagre

resources, but freeing William from any obligation to follow in his father’s footsteps.

What profession then, for a young man about to make his way in the world? Living

so close to the River Lea, the answer was on William’s doorstep. He decided to become

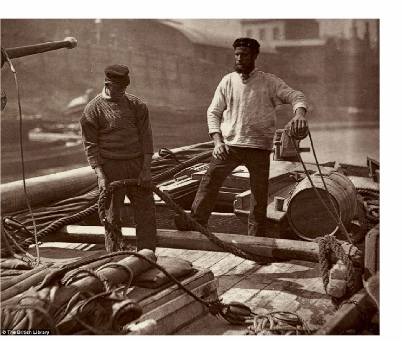

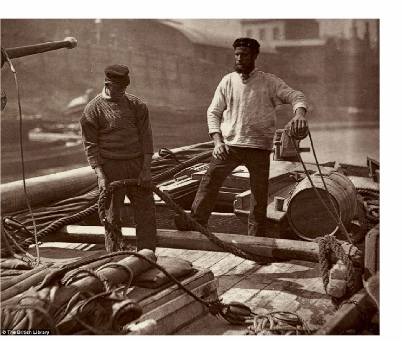

a lighterman. Before the days of mechanisation in the Port of London, lightermen

were essential to trade, transferring goods between ships and quays aboard flat-bottomed

barges called lighters. Even before the building of the Victoria Docks in 1855, there

were 90 acres of docks in London, including 35 acres of water, making the London

docks the largest in the world. Such was the spectacle that the docks was one of

the attractions that visitors to the capital flocked to see. The French critic and

historian, Hippolyte Taine came, came to London in 1859 and recorded in his journal:

“The number of canals by which the docks open into the body of the river ... are

streets of ships ... the innumerable riggings stretch a vast circle of spider-web

all round the rim of the sky... [they are] one of the mighty spectacles of our planet

… [the docks] are prodigious, overwhelming.”

It was usual for young men to be apprenticed at the age of 14, and in April 1861,

the 17-year old William declared his occupation as ‘lighterman’. There is no evidence

that he had been formally bound, but The Company of Watermen and Lightermen operated

a strict licensing system and there were heavy fines for watermen and lightermen

who operated without a licence or failed to produce their licence. He may have obtained

his two year licence which would have enabled him to work on the river.

A few years later, he was bound in another way. In the early 1860s he met Eliza Gregory.

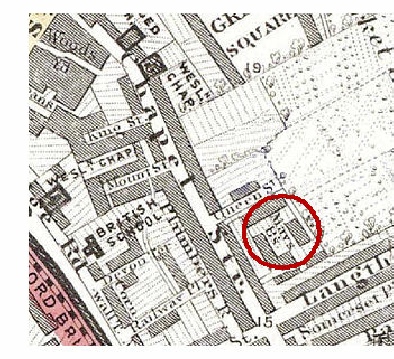

She was living with her family at Langthorne Street in Stratford, which was adjacent

to Chapel Street where William’s mother, Eleanor, was living. As well as being near

neighbours, Eliza’s brother, Thomas, was a bargeman. Thomas and William would certainly

have known each other so William most probably met Eliza through Thomas.  On 18 September

1864 William and Eliza were married at the Church of St Thomas in Stepney. The bride

and groom gave their residence as ‘Stepney’ and both made their mark in the register.

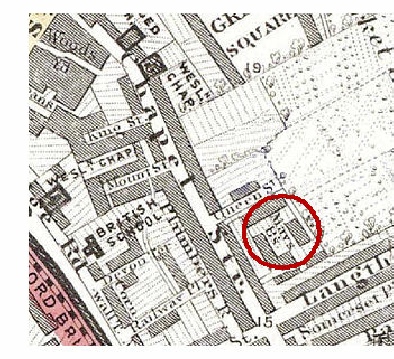

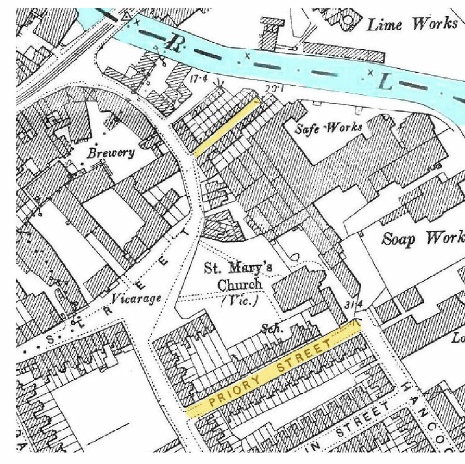

Their daughter, Maria, was born at about the time of their marriage. A second daughter,

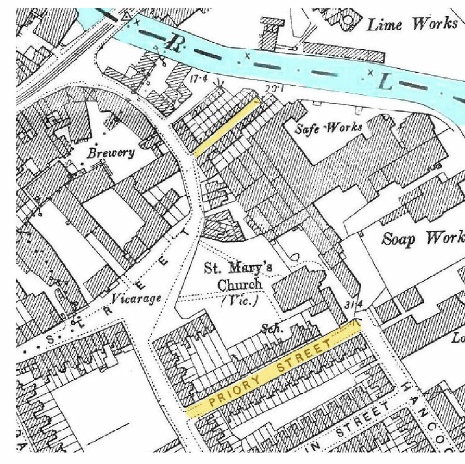

Eliza, followed in March 1867 while William and his family were living at 1 Mays

Buildings (see map).

On 18 September

1864 William and Eliza were married at the Church of St Thomas in Stepney. The bride

and groom gave their residence as ‘Stepney’ and both made their mark in the register.

Their daughter, Maria, was born at about the time of their marriage. A second daughter,

Eliza, followed in March 1867 while William and his family were living at 1 Mays

Buildings (see map).

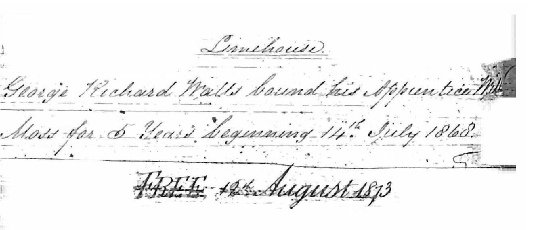

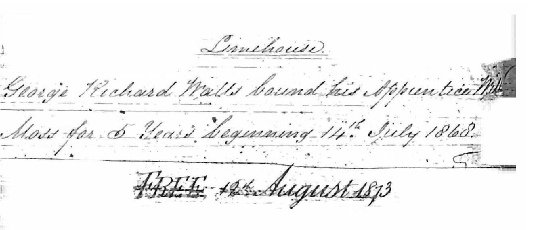

During this time, William continued to work on the river, saving what he could so

he could serve a formal apprenticeship. Such an arrangement meant several years on

low pay while the apprentice learnt his craft, and with a wife and two children to

support, it would have been difficult for William. However, in the Summer of 1868

he was apprenticed to George Richard Watts. Only a few years older than William,

George and his wife Louisa had no children, so George probably needed another hand

lightering; apprentices were also cheap labour, although perhaps with his experience,

William came to a more favourable arrangement with his master. Under the Company’s

rules, apprentices had to be  between the ages of 14 and 20 and were not allowed to

marry during their apprenticeship; in 1868 William was 25 and already married. The

fact that William completed his apprenticeship in five, rather than the usual seven,

years indicates that he had already obtained his two-year licence. On 12 August 1873

William became a ‘Freeman of the River’, the first of four generations of lightermen

in the Moss family. He had made it. By the skin of his teeth.

between the ages of 14 and 20 and were not allowed to

marry during their apprenticeship; in 1868 William was 25 and already married. The

fact that William completed his apprenticeship in five, rather than the usual seven,

years indicates that he had already obtained his two-year licence. On 12 August 1873

William became a ‘Freeman of the River’, the first of four generations of lightermen

in the Moss family. He had made it. By the skin of his teeth.

Crossing the river

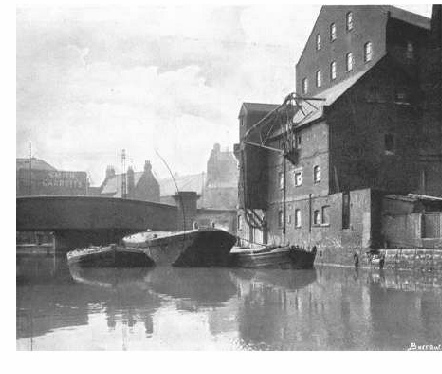

About the time he was bound as an apprentice, William moved his family to Bromley-by-Bow

on the Middlesex side of the River Lea. Most lightermen lived on this side of the

river and the location of Ammiel Terrace was a prime spot as it backed onto the tow

path of Bow Creek. The houses themselves were far from ideal; they were badly built

and, according to Charles Booth’s survey of London, had simply fallen down by 1899;

furthermore, Ammiel Terrace was located between a brewery, a soap works and a lime

works, just some of the noxious industries that had moved out of London after the

1844 Metropolitan Building Act. But at least William could afford to rent the whole

house; it was a far cry from Turnpike Row where, only seven years earlier, he had

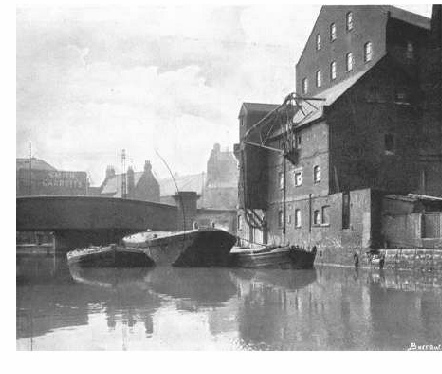

shared the house with his mother, sister and two other families. The photograph on

the right shows Bow Creek near the Bow Bridge; William may have been able to see

the view from Ammiel Terrace.

About the time he was bound as an apprentice, William moved his family to Bromley-by-Bow

on the Middlesex side of the River Lea. Most lightermen lived on this side of the

river and the location of Ammiel Terrace was a prime spot as it backed onto the tow

path of Bow Creek. The houses themselves were far from ideal; they were badly built

and, according to Charles Booth’s survey of London, had simply fallen down by 1899;

furthermore, Ammiel Terrace was located between a brewery, a soap works and a lime

works, just some of the noxious industries that had moved out of London after the

1844 Metropolitan Building Act. But at least William could afford to rent the whole

house; it was a far cry from Turnpike Row where, only seven years earlier, he had

shared the house with his mother, sister and two other families. The photograph on

the right shows Bow Creek near the Bow Bridge; William may have been able to see

the view from Ammiel Terrace.

During the years that followed, six more children were born. In addition to his rapidly

growing family, in 1871 William’s father-in-law, Thomas Gregory, and 16-year old

sister-in-law, Ann, were living at Ammiel Terrace, and probably being supported partially,

if not wholly, by William. Lightering generally paid good money and provided regular

work.

Over the years and as they reached their fourteenth birthdays, William apprenticed

six of his sons as lightermen; the first was William Thomas in 1884, and the last

was Walter in 1895; because of their closeness in age, there were four Moss apprentices

on the river in 1894; all of them, apart from Arthur, gained their freedom, so that

by 1909, at the end of William’s working life, there were five Moss lighterman working

the river from this one branch of the family.

Priory street

Mayhew, in his London Labour and the London Poor, observed that lighterman “as far

as their better circumstances have permitted them… have more comfortable homes [than

watermen]”. If Ammiel Terrace could be described as a ‘comfortable home’, then it

says little for the conditions that others lived in and sometime between 1881 and

1891, William and his family moved out. The move was prompted by necessity more than

desire: in the 1890s, Charles Booth observed that the hou ses in Ammiel Terrace were

“all jerry built, are now all down, were not pulled down but simply fell down of

themselves”, so by the time that William and his family moved out in the 1880s, the

house was not only becoming uninhabitable but dangerous.

ses in Ammiel Terrace were

“all jerry built, are now all down, were not pulled down but simply fell down of

themselves”, so by the time that William and his family moved out in the 1880s, the

house was not only becoming uninhabitable but dangerous.

They did not go far. Priory Street was a few streets south on the other side of the

Church of St Mary and a short walk from the river. Charles Booth may have held the

street in low esteem, commenting that it was the ‘resort of thieves’, but the house

had at least five rooms. William’s decision to undergo a formal apprenticeship and

gain his freedom had clearly paid off. Many working class families could not afford

such luxury.

It was while they were living at Priory Street that Eliza died age 52 on 9 November

1896 of cirrhosis of the liver and cardiac failure. Whilst, according to Charles

Booth, lightermen might be a sober class of men — for who would trust an intoxicated

lighterman — drink was a perennial problem for women as well as men. Booth noted

of nearby Devas Street that there were ‘public houses … with women sitting drinking,

with children of 3 or 4 years either on their laps or playing on the floor’.

Keeping it in the family

On 22 June 1897, six months after Eliza’s death, William returned to the Church of

St Thomas in Stepney, this time to marry Susan Dodson (née Brown). William managed

to sign his own name, although on later census returns he still ‘made his mark’.

Susan was a 53-year old widow originally from Paddington in London and was probably

related to William by marriage; in 1889, Eliza Moss had been a witness at the wedding

of her daughter, Eleanor (Ellen), to a lighterman by the name of Frederick Richard

Brown. The photograph on the right dates from about 1895 and is of Susan’s daughter

(also called Susan) from her first marriage to William Dodson. If the daughter resembled

her mother, the photograph would give some indication of what William’s second wife

may have looked like in her youth.

On 22 June 1897, six months after Eliza’s death, William returned to the Church of

St Thomas in Stepney, this time to marry Susan Dodson (née Brown). William managed

to sign his own name, although on later census returns he still ‘made his mark’.

Susan was a 53-year old widow originally from Paddington in London and was probably

related to William by marriage; in 1889, Eliza Moss had been a witness at the wedding

of her daughter, Eleanor (Ellen), to a lighterman by the name of Frederick Richard

Brown. The photograph on the right dates from about 1895 and is of Susan’s daughter

(also called Susan) from her first marriage to William Dodson. If the daughter resembled

her mother, the photograph would give some indication of what William’s second wife

may have looked like in her youth.

In 1901 William and Susan were living at 12 Donald Street. It backed on to Bromley

Sick Asylum, but as William was still bringing in a wage as a lighterman, he and

Susan could afford to rent the whole house. Ten years later, William, by now 68 years

old, was bringing home less money and he and Susan had moved to 5 Shenfield Place

where they rented two rooms. Despite earning a good wage during his lifetime, it

shows how difficult it was for working class people to make provision for their old

age and how tenuous life was for many.

Susan died on 28 November 1911 and was buried in Bow Cemetery, a memorial ‘in loving

memory’ card printed for her burial. William continued to live in the area. Early

in 1916 he contracted bronchitis and was admitted to the Poplar and Stepney Sick

Asylum where he died on 3 March. He was buried on 11 March in Tower Hamlets Cemetery.

because of their proximity to the famous Bow China Works which, although closed for

some 60 years by 1843, had been sited on the Essex side of the River Lea by the Bow

Bridge. This was just one of the early industries that had grown up around the River

Lea. However, it was in the nineteenth century that industrialisation really took

over, and not entirely to Stratford’s advantage. The 1844 Metropolitan Building Act

severely limited many toxic and noxious industries from operating in London and Middlesex.

As a result, many of these processes were moved across the Essex border to Stratford

and West Ham. Industries included rendering animal carcasses for tallow, soap and

glue, chemical plants for acids, pharmaceuticals or printing inks. The blend of ‘aromas’

would have delivered a constant affront to the nostrils. (The illustration above

shows the old Bow Bridge in 1837).

because of their proximity to the famous Bow China Works which, although closed for

some 60 years by 1843, had been sited on the Essex side of the River Lea by the Bow

Bridge. This was just one of the early industries that had grown up around the River

Lea. However, it was in the nineteenth century that industrialisation really took

over, and not entirely to Stratford’s advantage. The 1844 Metropolitan Building Act

severely limited many toxic and noxious industries from operating in London and Middlesex.

As a result, many of these processes were moved across the Essex border to Stratford

and West Ham. Industries included rendering animal carcasses for tallow, soap and

glue, chemical plants for acids, pharmaceuticals or printing inks. The blend of ‘aromas’

would have delivered a constant affront to the nostrils. (The illustration above

shows the old Bow Bridge in 1837). William’s

father also died in the 1850s, putting more financial strain on the family’s meagre

resources, but freeing William from any obligation to follow in his father’s footsteps.

William’s

father also died in the 1850s, putting more financial strain on the family’s meagre

resources, but freeing William from any obligation to follow in his father’s footsteps.

On 18 September

1864 William and Eliza were married at the Church of St Thomas in Stepney. The bride

and groom gave their residence as ‘Stepney’ and both made their mark in the register.

Their daughter, Maria, was born at about the time of their marriage. A second daughter,

Eliza, followed in March 1867 while William and his family were living at 1 Mays

Buildings (see map).

On 18 September

1864 William and Eliza were married at the Church of St Thomas in Stepney. The bride

and groom gave their residence as ‘Stepney’ and both made their mark in the register.

Their daughter, Maria, was born at about the time of their marriage. A second daughter,

Eliza, followed in March 1867 while William and his family were living at 1 Mays

Buildings (see map).  between the ages of 14 and 20 and were not allowed to

marry during their apprenticeship; in 1868 William was 25 and already married. The

fact that William completed his apprenticeship in five, rather than the usual seven,

years indicates that he had already obtained his two-

between the ages of 14 and 20 and were not allowed to

marry during their apprenticeship; in 1868 William was 25 and already married. The

fact that William completed his apprenticeship in five, rather than the usual seven,

years indicates that he had already obtained his two- About the time he was bound as an apprentice, William moved his family to Bromley-

About the time he was bound as an apprentice, William moved his family to Bromley- ses in Ammiel Terrace were

“all jerry built, are now all down, were not pulled down but simply fell down of

themselves”, so by the time that William and his family moved out in the 1880s, the

house was not only becoming uninhabitable but dangerous.

ses in Ammiel Terrace were

“all jerry built, are now all down, were not pulled down but simply fell down of

themselves”, so by the time that William and his family moved out in the 1880s, the

house was not only becoming uninhabitable but dangerous.  On 22 June 1897, six months after Eliza’s death, William returned to the Church of

St Thomas in Stepney, this time to marry Susan Dodson (née Brown). William managed

to sign his own name, although on later census returns he still ‘made his mark’.

Susan was a 53-

On 22 June 1897, six months after Eliza’s death, William returned to the Church of

St Thomas in Stepney, this time to marry Susan Dodson (née Brown). William managed

to sign his own name, although on later census returns he still ‘made his mark’.

Susan was a 53-