Lucy Briscoe (1841-1918)

Lucy was born in 1841 in Bromley-by-Bow. She became an inmate in Poplar Union Workhouse

in 1849 at the age of eight, along with her younger siblings. After the family left

the workhouse in 1851, she worked at whatever jobs she could get to supplement her

family’s meagre income and in 1861 was working as a match factory girl, a dangerous

occupation which, for many girls, resulted in illness and disease. In October 1866

Lucy returned to Poplar Union Workhouse. Heavily pregnant, she gave birth to a daughter

two weeks later on 29 October, one of ten young women who gave birth at the Workhouse

that quarter; six of the births, like hers, were illegitimate. There is no record

of what became of her daughter or what she was named, although it is possible that

the child survived and was known as Elizabeth Wake.

A little detective work was needed to piece together Lucy’s life from then on. The

1871 census shows a Lucy Wake living with a William Wake and his family at 20 Arthur

Street in Bromley-by-Bow with t wo children: Elizabeth Wake (born around 1866/7) and

William Wake (born around 1868); another child, Sarah Ann, followed in about 1873.

There is no record of a marriage between William and Lucy before William died in

the Summer of 1878, leaving Lucy with three young children.

wo children: Elizabeth Wake (born around 1866/7) and

William Wake (born around 1868); another child, Sarah Ann, followed in about 1873.

There is no record of a marriage between William and Lucy before William died in

the Summer of 1878, leaving Lucy with three young children.

Fortunately, her family had a solution and on 11 November 1878, Lucy married her

recently widowed brother-in-law, George Parkes, at Christ Church in Greenwich. The

marriage register shows George as a 50-year old widower and a salesman, and Lucy

as a 37-year old widow, living at Pleasant Place, Woodlands Grove near Maze Hill,

just a few minutes walk from Greenwich Park. As always, Alfred Biscoe and Elizabeth

Nash were on hand to act as witnesses.

A few years later, George, Lucy and Lucy’s three children by William Wake were living

at Borough Market (shown above). Shortly after the night of the census in April 1881,

Lucy and George’s daughter, Beatrix, was born, followed by George in June 1885. Both

children were baptised at the Church of St Saviour in Southwark within sight of Borough

Market.

George prospered and sometime in the late 1880s he and his family moved to the suburbs,

settling on 12 Relf Road, a pleasant six-roomed house in a tree lined street in Peckham

Rye. George did not enjoy the suburban life for long, dying in the Summer of 1890

aged 61.  Lucy continued to live at Relf Road with her family, who left home one by

one to marry and start their own families: her daughters, Sarah Ann Wake and Beatrix

Parkes marryied two brothers, George and Arthur Chart.

Lucy continued to live at Relf Road with her family, who left home one by

one to marry and start their own families: her daughters, Sarah Ann Wake and Beatrix

Parkes marryied two brothers, George and Arthur Chart.

Lucy died on 8 February 1918. Her estate, which she left to her daughters, Sarah

Ann Chart and Beatrix Chart, was valued at £1,016 - about seven years’ wages for

a craftsman. She had come a long way from Poplar Workhouse and the slum alleys of

Bromley-by-Bow.

Rebecca Biscoe (1847-1919)

Rebecca was born in May 1847 and baptised the following month at the Church of St

Mary. After leaving Poplar Workhouse in 1851 she lived with her eldest sister, Harriet,

in Lambeth. In 1861, although only 13 years old, she was nursing a three-year old

child. Little more is known about Rebecca after this date, although there are two

instances which deserve mention. On 1 December 1865, a 17-year old Rebecca Bristow

entered Poplar Workhouse and was discharged on 5 February 1866 after giving birth

to a baby boy. And on 15 September 1867, a Rebecca Biscoe married William Penn, a

smith, at the Church of St James the Great in Bethnal Green. Although her father’s

name was given as James Biscoe (deceased), one of the two witnesses was Elizabeth

Nash, so it is likely that the father’s name was recorded incorrectly on the marriage

register and this Rebecca was the daughter of William and Harriet Biscoe.

Alfred Biscoe (1849-1919)

The youngest of the eleven Biscoe children, Alfred was born in August 1849 in Bromley-by-Bow,

shortly before his mother and siblings entered Poplar Union Workhouse. Against the

odds (infant mortality rates in workhouses were notoriously bad), Alfred survived,

leaving the workhouse with his family in 1851. Indeed, perhaps without the, albeit

meagre diet that the workhouse provided, Alfred would not have survived infancy.

Once outside the walls of the Workhouse, Alfred worked as soon as he was able, helping

to support his widowed mother. He worked firstly as a match factory boy, a job which

could pay up to 7s a week. Even before that, he may have helped make match boxes

at home. It was one of the most tedious and least lucrative of home working jobs,

but could be carried out by women and children at home. A woman would collect the

wood, labels and sandpaper from the match company’s depot,  but was expected to supply

her own glue. The going rate for making boxes was 2¼d for every gross (144); an experienced

box maker and her family could make eight gross a day, bringing in 1s 6d, about half

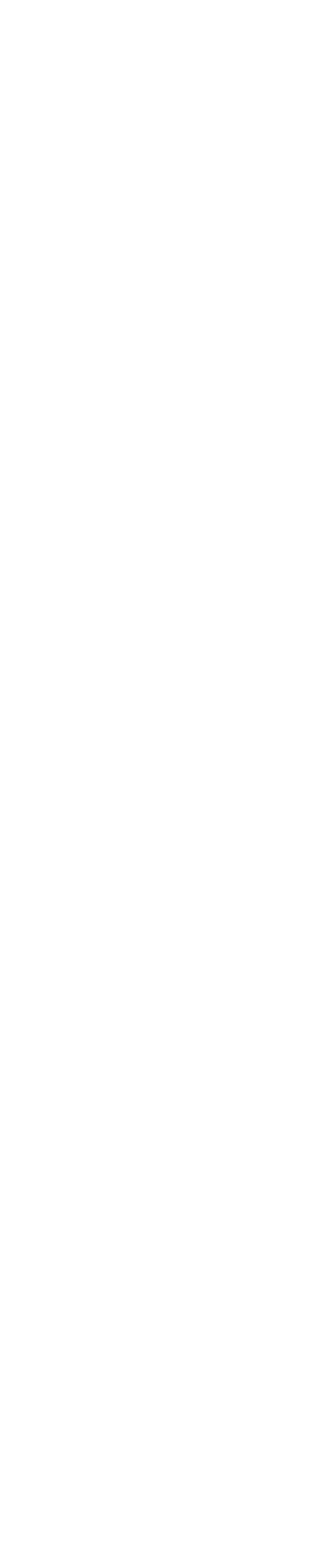

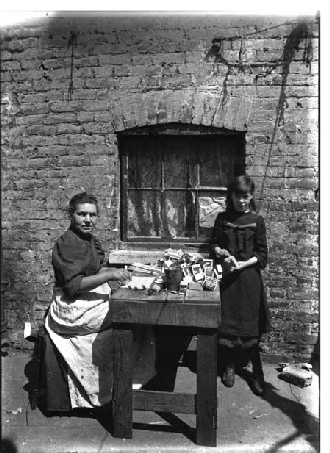

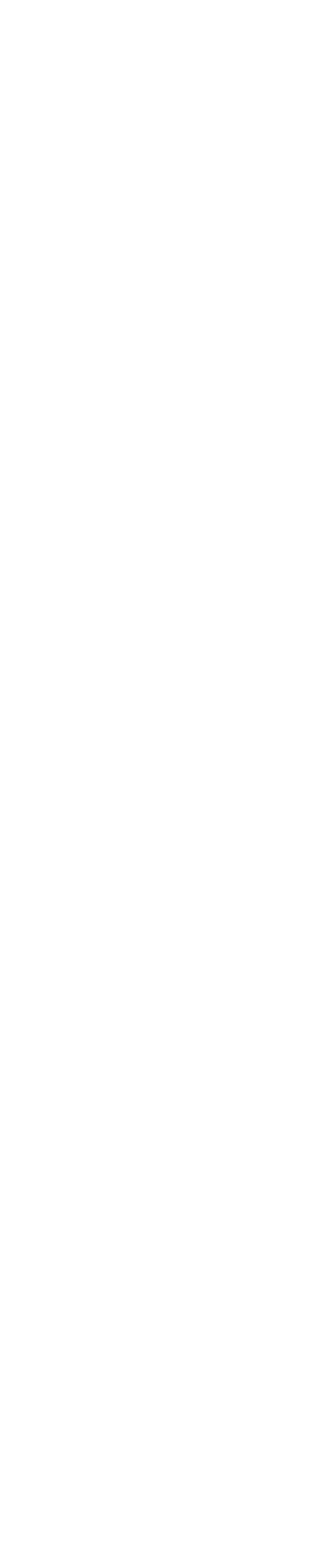

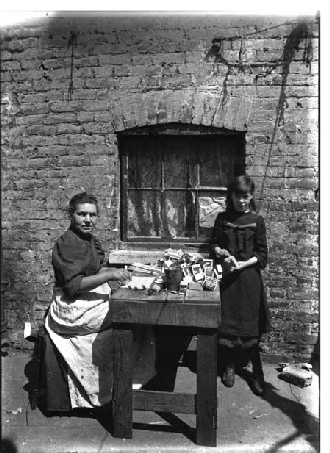

the weekly rent for a one-room accommodation. The photograph on the left dates from

about 1900 and shows a mother and her daughter making match boxes at home.

but was expected to supply

her own glue. The going rate for making boxes was 2¼d for every gross (144); an experienced

box maker and her family could make eight gross a day, bringing in 1s 6d, about half

the weekly rent for a one-room accommodation. The photograph on the left dates from

about 1900 and shows a mother and her daughter making match boxes at home.

Albert’s older brother, Charles, was working as a labourer in an iron foundry, and

perhaps he was able to get Alfred a job, as by 1870 Alfred was working as an iron

moulder. With a steady income and learning a trade, he could think about settling

down and on Christmas Day 1870, he married Sarah Church at the Church of St Paul

on Bow Common. Sarah had been born in Leighton Buzzard but had lived in a number

of locations with her family before they settled in Bromley-by-Bow in about 1860.

Her mother and brother, Mary and Robert Church, acted as witnesses to the marriage,

although both made their mark (‘x’) unlike the bride and groom who signed their own

names. After their marriage, they moved to 12 Egleton Road,  with Sarah’s widowed

mother, Mary. Over the next several years, Sarah gave birth to three children, but

the marriage was short-lived and Sarah died in early 1878.

with Sarah’s widowed

mother, Mary. Over the next several years, Sarah gave birth to three children, but

the marriage was short-lived and Sarah died in early 1878.

The following year, on 5 March 1879, Alfred took his three children to the Church

of St Mary in Bromley-by-Bow to have them baptised; perhaps he had made a promise

to Sarah before she died. Three months later, on 2 June, he returned to the Church

of St Paul where he married Fanny Eagle. She was a 33-year old widow with three children

from her previous marriage. The 1881 census shows Alfred and his family living at

13 Eagling Road. As well as the six children from Alfred’s and Fanny’s first marriages,

there was an eight-month old baby named Alfred. Sharing the house was a pantomime

artist called Tully Louis and his family. In an era before radio and television,

pantomimes were even more popular at Christmas than they are today and Tully appeared

regularly at the Theatre Royal in Drury Lane where his signature role was Pantaloon,

the greedy, elderly father of Columbine who assists Clown in his tricks, and one

of the five main characters of the Harlequinade. He must have made an interesting

and flamboyant neighbour.

Over the years, Alfred and his family lived at various addresses in Bromley-by-Bow,

including 13 Bruce Road, before moving to Forest Gate in the 1900s. At the time,

Alfred was working as an engine fitter for the Great Eastern Railway Company. Conveniently

for Alfred, the company’s works were at Stratford, which still holds the record,

set in 1891, for the fastest time to build a locomotive (9 hours 47 minutes) — perhaps

Alfred was part of the record-breaking team of fitters. Alfred and Fanny continued

to live in the area until they died: Fanny in 1914 and Alfred in 1919.

Harriet Briscoe (1830-1877)

The eldest of the Briscoe children, Harriet was born in Stepney, the only one of

the Briscoe children not to have been born in Bromley-by-Bow. She was baptised at

the Church of St Dunstan on 8 August 1830 . She was working as a servant when, in

1847, she met George Parkes. He had been born in Limehouse, but at the time he met

Harriet was living in Kennington Lane which ran along the side of the famous Vauxhall

Gardens (shown on this map of about 1850). Although both minors, they married on

19 April 1847 at the Church of St Mark in Kennington with parental consent; there

is evidence that George’s father, William, was present at their wedding. The marriage

certificate gives George’s occupation as ‘mariner’ although he probably stated his

occupation as ‘farrier’ and was mis-heard, since he is later recorded as a blacksmith.

The print below shows Kennington Common with the church of St Mark visible in the

distance.

. She was working as a servant when, in

1847, she met George Parkes. He had been born in Limehouse, but at the time he met

Harriet was living in Kennington Lane which ran along the side of the famous Vauxhall

Gardens (shown on this map of about 1850). Although both minors, they married on

19 April 1847 at the Church of St Mark in Kennington with parental consent; there

is evidence that George’s father, William, was present at their wedding. The marriage

certificate gives George’s occupation as ‘mariner’ although he probably stated his

occupation as ‘farrier’ and was mis-heard, since he is later recorded as a blacksmith.

The print below shows Kennington Common with the church of St Mark visible in the

distance.

After their marriage, George and Harriet returned to Bromley-by-Bow, and in 1851

were living in Vicarage House which, contrary to its genteel sounding name, housed

four families. George, like his father, was working as a blacksmith. By 1861 Harriet

and George had returned to Lambeth where they were living at Rutland Street. George

was still working as a blacksmith and Harriet was sewing shirts. It was low paid

work: she could earn 6s for a dozen shirts, although she could only make one shirt

in a long day, and had to pay for thread and buttons, and candles to see by in the

winter, and so rarely cleared more than 2s a week. There was good reason why this

work was known as the ‘slop’ trade.

four families. George, like his father, was working as a blacksmith. By 1861 Harriet

and George had returned to Lambeth where they were living at Rutland Street. George

was still working as a blacksmith and Harriet was sewing shirts. It was low paid

work: she could earn 6s for a dozen shirts, although she could only make one shirt

in a long day, and had to pay for thread and buttons, and candles to see by in the

winter, and so rarely cleared more than 2s a week. There was good reason why this

work was known as the ‘slop’ trade.

But Harriet and George had plans. They worked hard and saved diligently and by 1871

were living at 10 Borough Market where George was working as a green grocer buying

and selling fruit. Unfortunately, the improvement in their lives came too late for

Harriet who died on 30 May 1877 of chronic bronchitis. As for George, he choose another

Briscoe as a wife (see Lucy Briscoe below).

Elizabeth Briscoe (1831-1877)

Elizabeth was born on 19 July 1831 and baptised a month later at the Church of St

Mary in Bromley-by-Bow. On 27 May 1849, just months before her family entered Poplar

Union Workhouse, she married Thomas Nash at the Church of St Dunstan in Stepney.

By 1861, Elizabeth and Thomas were living at 1 Kings Head Yard in Bromley-by-Bow

with their four children.

Sometime between 1861 and 1871, the family moved to Oliver Court, one of a network

of courtyards and alleys off the High Street. Elizabeth and her family remained here

for 20 or more years, unusual for a working class family in the nineteenth century,

when it was not uncommon for families to move almost every year. If Oliver Court

was the seat of the Nash and Biscoe families, then Elizabeth, the eldest of the Briscoe

siblings living there, was its matriarch. She appears to be the thread that bound

the families together and, although she could neither read nor write, she acted as

a witness at the marriages of a number of her younger siblings. Even from the few

official documents that bear Elizabeth’s name, her strength of character shines through,

so perhaps it was Elizabeth who was instrumental in helping her mother and siblings

leave the workhouse in April 1851, rather than her father.

Click on the names below to find out about the children of William and Harriet Briscoe

wo children: Elizabeth Wake (born around 1866/7) and

William Wake (born around 1868); another child, Sarah Ann, followed in about 1873.

There is no record of a marriage between William and Lucy before William died in

the Summer of 1878, leaving Lucy with three young children.

wo children: Elizabeth Wake (born around 1866/7) and

William Wake (born around 1868); another child, Sarah Ann, followed in about 1873.

There is no record of a marriage between William and Lucy before William died in

the Summer of 1878, leaving Lucy with three young children.  Lucy continued to live at Relf Road with her family, who left home one by

one to marry and start their own families: her daughters, Sarah Ann Wake and Beatrix

Parkes marryied two brothers, George and Arthur Chart.

Lucy continued to live at Relf Road with her family, who left home one by

one to marry and start their own families: her daughters, Sarah Ann Wake and Beatrix

Parkes marryied two brothers, George and Arthur Chart.  but was expected to supply

her own glue. The going rate for making boxes was 2¼d for every gross (144); an experienced

box maker and her family could make eight gross a day, bringing in 1s 6d, about half

the weekly rent for a one-

but was expected to supply

her own glue. The going rate for making boxes was 2¼d for every gross (144); an experienced

box maker and her family could make eight gross a day, bringing in 1s 6d, about half

the weekly rent for a one- with Sarah’s widowed

mother, Mary. Over the next several years, Sarah gave birth to three children, but

the marriage was short-

with Sarah’s widowed

mother, Mary. Over the next several years, Sarah gave birth to three children, but

the marriage was short- . She was working as a servant when, in

1847, she met George Parkes. He had been born in Limehouse, but at the time he met

Harriet was living in Kennington Lane which ran along the side of the famous Vauxhall

Gardens (shown on this map of about 1850). Although both minors, they married on

19 April 1847 at the Church of St Mark in Kennington with parental consent; there

is evidence that George’s father, William, was present at their wedding. The marriage

certificate gives George’s occupation as ‘mariner’ although he probably stated his

occupation as ‘farrier’ and was mis-

. She was working as a servant when, in

1847, she met George Parkes. He had been born in Limehouse, but at the time he met

Harriet was living in Kennington Lane which ran along the side of the famous Vauxhall

Gardens (shown on this map of about 1850). Although both minors, they married on

19 April 1847 at the Church of St Mark in Kennington with parental consent; there

is evidence that George’s father, William, was present at their wedding. The marriage

certificate gives George’s occupation as ‘mariner’ although he probably stated his

occupation as ‘farrier’ and was mis- four families. George, like his father, was working as a blacksmith. By 1861 Harriet

and George had returned to Lambeth where they were living at Rutland Street. George

was still working as a blacksmith and Harriet was sewing shirts. It was low paid

work: she could earn 6

four families. George, like his father, was working as a blacksmith. By 1861 Harriet

and George had returned to Lambeth where they were living at Rutland Street. George

was still working as a blacksmith and Harriet was sewing shirts. It was low paid

work: she could earn 6