Early years

Esther was baptised on 22 March 1821 at Christ Church in the heart of Spitalfields,

the daughter of Charles Steward and Mary Ducro. Her father died in February 1824

when she was less than three years old, and although her grandmother, Ann Ducro,

had a small income, the loss of her father undoubtedly put a strain on the families

finances. As a result, from a young age, she learnt how to split and plait straw,

which was then used in the making of straw bonnets.

Esther was baptised on 22 March 1821 at Christ Church in the heart of Spitalfields,

the daughter of Charles Steward and Mary Ducro. Her father died in February 1824

when she was less than three years old, and although her grandmother, Ann Ducro,

had a small income, the loss of her father undoubtedly put a strain on the families

finances. As a result, from a young age, she learnt how to split and plait straw,

which was then used in the making of straw bonnets.

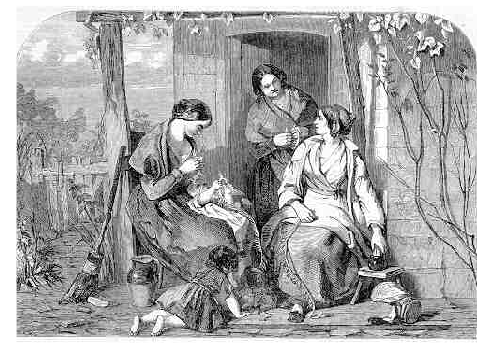

Straw plaiting was a thriving cottage industry and children as young as three were

employed, their pliant fingers well suited to the dexterous work. The heyday came

with the Napoleonic wars, when blockade and high import duties excluded foreign and

especially Italian plait. At a time when the average Hertfordshire agricultural wage

was between 10s and 12s a week, straw plaiting wives could earn appreciably more

than their husbands, and children’s contributions to the family income were considerable.

Esther’s straw plaiting, and the industry of her siblings, would have bee n an important

part of her family’s income. Unlike many children who often did not get an education

because they could “…learn the craft, and their parents are hard to convince that

paying for their schooling is necessary when they can earn a living instead" (Government

report, 1842), Esther learnt to read and write.

n an important

part of her family’s income. Unlike many children who often did not get an education

because they could “…learn the craft, and their parents are hard to convince that

paying for their schooling is necessary when they can earn a living instead" (Government

report, 1842), Esther learnt to read and write.

‘Marry in haste, repent at leisure’

Although the youngest of her siblings, Esther found a husband at a young age. Perhaps

without a father, she was eager not to end up like her three older sisters all of

whom remained spinsters. Only three months after her sister, Eliza, had married,

Esther married George Bostock. The wedding took place on 29 September 1839 at the

Church of St John the Baptist in Hackney; Esther was 18 years old.

George Bostock was a stenciller whose father, James, was on the way to becoming not

only a successful business man, but a gentleman (that is, he had an income to live

off of without having to work). No doubt Esther began married life with high expectations,

but it is likely that it did not promise all she had hoped. Her mother-in-law, with

whom George and Esther lived had a sharp tongue, and George’s father had left his

wife to live with a younger relative. There is evidence to suggest that George drunk

himself into an early grave and where there is alcoholism, domestic violence is often

not far behind. If it had not been for her five young children, Esther might have

been relieved when George died on 11 December 1853 leaving her a young widow. For

the whole of her married life, Esther had lived with her mother-in-law, and one might

have expected this arrangement to continue after George’s death; but this was not

the case. Sometime after 1854 Esther met Thomas Hockerday. He was a carpenter so

it is possible that he was an acquaintance of her husband. Although Esther was widowed

and free to marry, Thomas was still married, having married for the third time in

1854. Despite this, Esther lived with Thomas, giving birth to a daughter on 6 January

1858, who was named Emily Adelaide. Still in her thirties, perhaps Esther wanted

to make a new life for herself; or perhaps she was just desperate to get away from

her husband’s family.

Twice widowed

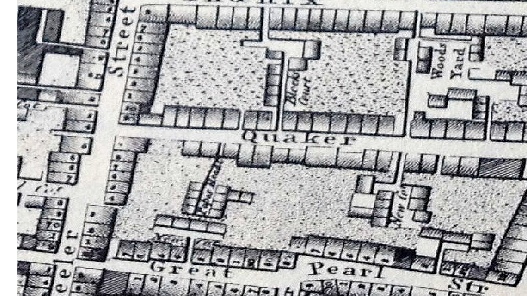

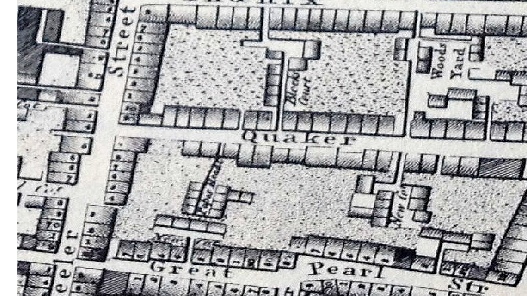

At  the time of Emily’s birth, Thomas and Esther were living at 5 York Street in Shoreditch,

on the edge of the notorious slum known as the Old Nichol (it is shown in the map

just above the Great Eastern Railway Station). Two years later, the family moved

to 139 Holywell Street (Shoreditch High Street), and it was here that Esther gave

birth to a son, Thomas Henry, on 28 February 1860. He was baptised at the nearby

church of St Leonard. Five years later, in 1865, the family were living at New Inn

Yard, which runs east-west from Curtain Road to Shoreditch High Street (and is shown

at the top of the map). Like York Street, it was slum housing. An article written

by John Hollingshead entitled, ‘Ragged London in 1861’ paints a vivid and depressing

picture of these locations. It is worth quoting at length here:

the time of Emily’s birth, Thomas and Esther were living at 5 York Street in Shoreditch,

on the edge of the notorious slum known as the Old Nichol (it is shown in the map

just above the Great Eastern Railway Station). Two years later, the family moved

to 139 Holywell Street (Shoreditch High Street), and it was here that Esther gave

birth to a son, Thomas Henry, on 28 February 1860. He was baptised at the nearby

church of St Leonard. Five years later, in 1865, the family were living at New Inn

Yard, which runs east-west from Curtain Road to Shoreditch High Street (and is shown

at the top of the map). Like York Street, it was slum housing. An article written

by John Hollingshead entitled, ‘Ragged London in 1861’ paints a vivid and depressing

picture of these locations. It is worth quoting at length here:

“Walk along the main thoroughfare from the parish church towards the city, peep on

one side of the hay-bundle standing at the corn-chandler's door; look through the

group of rough, idle loungers, leaning against the corner of the gin-shop, or dive

under the fluttering garments that hang across outside the cheap clothier's window,

and you will see a dark, damp opening in the wall, like the channel of a sewer passing

under and between the houses, and leading to one of the wretched courts and alleys.

You enter the passage, picking your way to the bottom, and find a little square of

low, black houses, that look as they were built as a penal settlement for dwarfs.

The roofs are depressed, the doors are narrow, the windows are pinched up, and the

whole square can almost be touched on each side by a full-grown man. At the further

end you will observe a tap, enclosed in a wooden frame, that supplies the water for

the whole court, with a dust-bin and privy, which are openly used by all…Glancing

over the tattered green curtain at one of the black windows, you will see a room

like a gloomy well…In some cases these courts are choked up with every variety of

filth; their approaches wind round by the worst kind of slaughter-houses; they lie

in the midst of rank stables and offensive trades; they are crowded with pigs, with

fowls, and with dogs; they are strewn with oyster-shells and fish refuse; they look

upon foul yards and soaking heaps of stale vegetable refuse; their drainage lies

in pools wherever it may be thrown; the rooms of their wretched dwellings have not

been repaired or whitewashed for years; … and they are often smothered with smoke,

which beats down upon them from some neighbouring factory, whose chimney is beyond

the control of the Act of Parliament… New Inn Yard, Shoreditch, is another of the

worst; and the whole line of Holywell Lane, on either side, is full of these holes

and corners.”

One of the results of these damp, polluted, unsanitary living conditions was respiratory

diseases. On 26 February 1865, Esther became a widow for the second time, when Thomas

died suddenly of chronic bronchitis. This time, Esther has two children under seven

years of age.

Making ends meet

Presumably by this stage, Esther’s life was so far removed from that of her mother

and sisters in Spitalfields that she could not turn to them for help. After her husband’s

death, Esther continued to earn her living by making straw bonnets, although doing

so became increasingly difficult; in 1865, cheap foreign plait started to be imported

from the Far East and the British industry went into rapid decline. Even so, the

1871 census shows that Esther was still working as a ‘fancy bonnet maker’. At this

time, she was living at 26 Hoxton Street, Shoreditch, with her two children by Thomas

Hockerday: Emily, who was employed as a domestic servant, and Thomas, who was working

as an errand boy; also living with them was Edwin Francis Bostock, Esther’s son from

her first marriage, by now 18 years old and a cabinet maker. This is a little surprising

given that Edwin had lived with his grandmother, Maria Antoinette Bostock, since

his father’s death, and in 1871 his grandmother was living on her own in a house

in Bethnal Green. It appears that Esther’s children had not forgotten her after all.

In 1877, Esther’s daughter, Emily, married a 20-year old boot finisher by the name

of Benjamin Fowle. The following year Edwin Francis Bostock married Mary Ann Jeffrey,

the daughter of a French polisher. Not long after, Esther, and her son, Thomas, moved

in with the Emily and her family, and Thomas learnt the trade of boot finisher, working

alongside Benjamin; Esther continued to make fancy bonnets. At the time, the family

were living at 24 Waterlow Street in Shoreditch.

This domestic arrangement clearly suited all concerned, and it endured until at least

1891 when Esther and the family were living at 6 Goring Street in Hackney, described

by Charles Booth as a “thieves nest”, although he found that the area had an “independent

and easy going” air. Esther, by now 70-years old, was still contributing to the family’s

income through her millinery skills. She also leant a hand helping her daughter care

for her seven children.

A reversal of fortunes

In the Summer of 1895, Emily died; she was only 37 years old. After burying her daughter,

Esther may have continued living with her son-in-law, Benjamin, and her grandchildren,

but within a few years, Benjamin was either married to or living with a lady called

Marion. She was a french polisher with seven children of her own and was most likely

an acquaintance of Benjamin’s eldest daughter, Emily, who was also a french polisher.

French polishing was one of the many skilled furniture-finishing trades at which

women tended to excel, working from home and often earning good wages, with no need

for a long, formal training or an apprenticeship. In the 1880s there were 250 female

french polishers in Bethnal Green and Shoreditch, and some went on to run their own

workshops. As such, many young man hoped to attract and marry a french polisher.

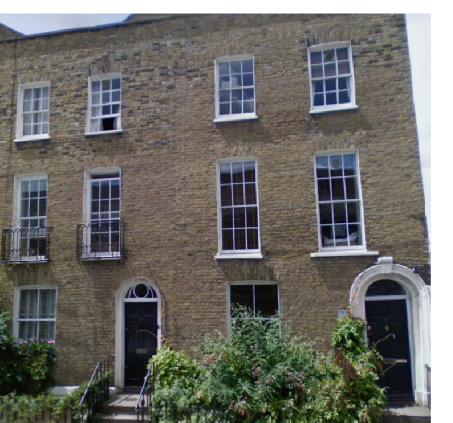

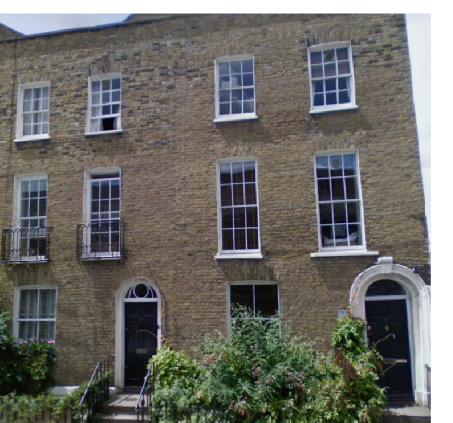

A few years later, Benjamin and Marion were living at 125 Great Cambridge Street,

Haggerston (now called Queensbridge Road). The only old houses remaining on the street

today are attractive three-storey (plus basement) Regency town house (pictured  on

the left). Today they are desirable properties but in 1901 there were 18 people living

in number 125: Benjamin, Marion and 12 of their children, ranging in ages from two

to twenty-one; plus a family of four that occupied two rooms. As a result, there

was no room for the 80-year old Esther either that, or Benjamin did not want his

former mother-in-law living with him.

on

the left). Today they are desirable properties but in 1901 there were 18 people living

in number 125: Benjamin, Marion and 12 of their children, ranging in ages from two

to twenty-one; plus a family of four that occupied two rooms. As a result, there

was no room for the 80-year old Esther either that, or Benjamin did not want his

former mother-in-law living with him.

Homeless and unable to earn her own living, Esther had no option but to apply to

the parish for assistance, and in 1901 she was an inmate in the Hackney Union Workhouse.

Her son, Thomas Hockerday, was living not far away at 87 Morning Lane with his wife,

Sarah, and their five children.

Esther remained in the Workhouse for the next five years, dying on 12 March 1906

of senile decay. She had lived for 85 years, many of which had been a battle for

survival. Sarah Hockerday, her daughter-in-law, registered her death.

Esther was baptised on 22 March 1821 at Christ Church in the heart of Spitalfields,

the daughter of Charles Steward and Mary Ducro. Her father died in February 1824

when she was less than three years old, and although her grandmother, Ann Ducro,

had a small income, the loss of her father undoubtedly put a strain on the families

finances. As a result, from a young age, she learnt how to split and plait straw,

which was then used in the making of straw bonnets.

Esther was baptised on 22 March 1821 at Christ Church in the heart of Spitalfields,

the daughter of Charles Steward and Mary Ducro. Her father died in February 1824

when she was less than three years old, and although her grandmother, Ann Ducro,

had a small income, the loss of her father undoubtedly put a strain on the families

finances. As a result, from a young age, she learnt how to split and plait straw,

which was then used in the making of straw bonnets.  n an important

part of her family’s income. Unlike many children who often did not get an education

because they could “…learn the craft, and their parents are hard to convince that

paying for their schooling is necessary when they can earn a living instead" (Government

report, 1842), Esther learnt to read and write.

n an important

part of her family’s income. Unlike many children who often did not get an education

because they could “…learn the craft, and their parents are hard to convince that

paying for their schooling is necessary when they can earn a living instead" (Government

report, 1842), Esther learnt to read and write.  the time of Emily’s birth, Thomas and Esther were living at 5 York Street in Shoreditch,

on the edge of the notorious slum known as the Old Nichol (it is shown in the map

just above the Great Eastern Railway Station). Two years later, the family moved

to 139 Holywell Street (Shoreditch High Street), and it was here that Esther gave

birth to a son, Thomas Henry, on 28 February 1860. He was baptised at the nearby

church of St Leonard. Five years later, in 1865, the family were living at New Inn

Yard, which runs east-

the time of Emily’s birth, Thomas and Esther were living at 5 York Street in Shoreditch,

on the edge of the notorious slum known as the Old Nichol (it is shown in the map

just above the Great Eastern Railway Station). Two years later, the family moved

to 139 Holywell Street (Shoreditch High Street), and it was here that Esther gave

birth to a son, Thomas Henry, on 28 February 1860. He was baptised at the nearby

church of St Leonard. Five years later, in 1865, the family were living at New Inn

Yard, which runs east- on

the left). Today they are desirable properties but in 1901 there were 18 people living

in number 125: Benjamin, Marion and 12 of their children, ranging in ages from two

to twenty-

on

the left). Today they are desirable properties but in 1901 there were 18 people living

in number 125: Benjamin, Marion and 12 of their children, ranging in ages from two

to twenty-