Early years

When Mary was born in about 1782 to Stephen and Ann Ducro, George III was on the

throne; Britain was at war, not with her old adversary, France, but with her most

troublesome colony, America; the Prime Minister, Lord North, had just stepped down

after a vote of no confidence; and the first convict ships would not leave Portsmouth

for Botany Bay for another five years.

When Mary was born in about 1782 to Stephen and Ann Ducro, George III was on the

throne; Britain was at war, not with her old adversary, France, but with her most

troublesome colony, America; the Prime Minister, Lord North, had just stepped down

after a vote of no confidence; and the first convict ships would not leave Portsmouth

for Botany Bay for another five years.

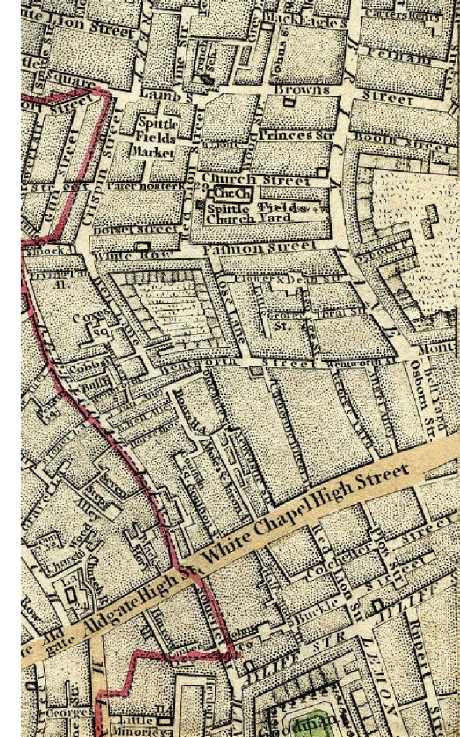

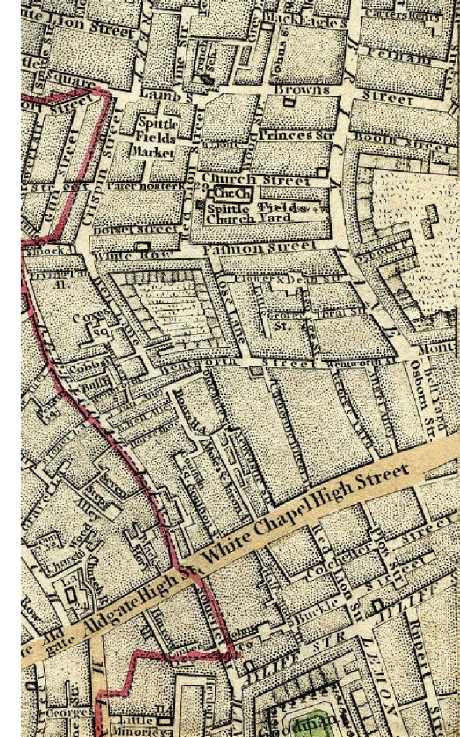

Mary was born in Whitechapel, just south of Spitalfields, the Whitechapel Road separating

the two parishes. Although the population of London had increased, it was still under

a million, and Spitalfields, although densely populated, marked the north eastern

limits of the City.

It is difficult to know her family’s situation, but they were certainly able to provide

Mary with a basic education. As her mother, Ann, could not write, Mary may have been

taught by another relative, or she may have attended the Charity School in Red Lion

Street: established earlier that century, a new school building was erected in 1782

and admitted all children between the ages of eight and ten whose parents resided

within half a mile of the school; no fees were charged.

As well as gaining a basic education, Mary learnt to weave from a young age. Although

her father was a bricklayer, some of her family and many of her neighbours were

weavers. It was not unusual for children to start learning to weave from as young

as six or seven. Mary first learnt to wind or quill the silk, then pick the silk

and pull the warp on the loom beam. In later life, Mary described herself as a ‘silk

warper’ - that is the person who set the up and down threads on the loom ready for

the shuttle to be passed through them and the cloth to be woven - so may not have

worked the loom itself, although no doubt she would have been able to weave a plain

piece of cloth. In the Summer of 1804, Mary and her parents were living in Phoenix

Street when her father died. Fortunately, her mother had income from an independent

source and was able to sustain the family. A few years after her father’s death,

Mary met Charles Steward, a local carpenter; perhaps he had been an acquaintance

of her father’s in the building trade. They were married on a Monday, 3 September

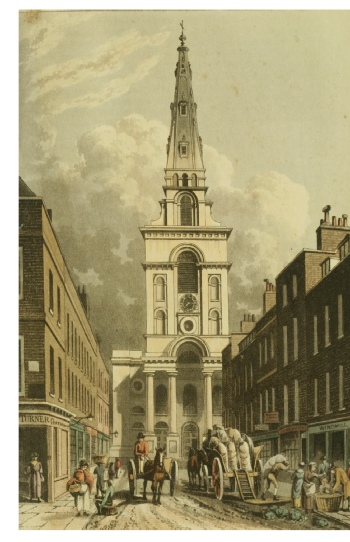

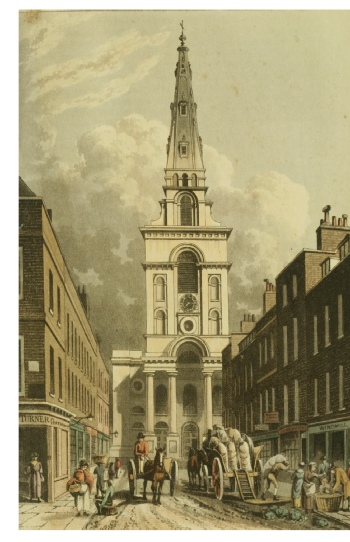

1810 at Christ Church. Both bride and groom signed their names. The engraving below

shows Christ Church in about 1815.

Married life

Over the next thirteen years, Mary gave birth to eight children, about one every

two years, followed by twin boys in February 1823; they died before they could be

baptised and were buried on 10 February 1823 at Christ  Church. During this time,

Mary and her family were living at Crown Court, situated in the area behind Quaker,

Wheeler and Phoenix Streets.

Church. During this time,

Mary and her family were living at Crown Court, situated in the area behind Quaker,

Wheeler and Phoenix Streets.

Until 1815, Britain had been at war with France and French imports, such as silk,

were banned. Once the war ended in the Summer of 1815, conditions declined rapidly

for the weavers of Spitalfields. Indeed, so great was their suffering that on 26

November 1816, a public meeting was held at the Mansion House for their relief. It

was stated that two-thirds of weavers were without employment and without the means

of support, that “some had deserted their houses in despair unable to endure the

sight of their starving families, and many pined under languishing diseases brought

on by the want of food and clothing”, and that the distress among the silk weavers

was so intense that “it partook of the nature of a pestilence which spreads its contagion

around and devastates an entire district.” It was during these difficult conditions,

in February 1824, that Mary’s husband, Charles died leaving her with six children.

Widowhood

Mary’s mother, Ann Ducro, who had been widowed since 1804, came to Mary’s aid and

mother, daughter, and the six children (five girls and one boy) lived together. By

the 1841 census, Mary, her mother and her two unmarried daughters, Mary Ann and Ann

Martha were living at 2 Wilkes Street (previously Wood Street) in Spitalfields (Eliza

and Esther had married in 1839, and Sarah Ann had left home to work as a cook). To

supplement Ann’s income, the three Steward ladies carried out work at home: Mary

Ann was a dress maker, and Ann a straw bonnet maker. Mary continued to work as a

silk warper, although between 1824 and 1835, the number of looms in operation fell

by two-thirds and wages dropped by a third, from about eight or nine shillings to

no more than seven shillings and six pence a week; the photograph below shows the

garret of a house in Fournier Street (formerly Church Street), the notches in the

beams indicating from where the looms would have been hung.

In 1845, Mary’s mother died and presumably her ‘independent means’ with her. In 1851,

Mary and her daughters, now 39 and 34-years old, were living on the north side of

Browns Lane (renamed Hanbury Street in 1876). The houses in Browns Lane had been

built the previous century and were single-fronted three-storey buildings with a

roof garret, each storey consisting of two rooms. Also living at number 25 were two

dressmakers, slipper makers, shoe makers, stay makers and a baker — in all 14 people

making up six families: one family to a room — so Mary’s financial situation, like

the area, had deteriorated. Neighbouring 29 Hanbury Street became infamous 30 years

later when the mutilated body of Annie Chapman was found by the doorway of the backyard;

she was the second victim of the serial killer who became known as ‘Jack the Ripper’.

built the previous century and were single-fronted three-storey buildings with a

roof garret, each storey consisting of two rooms. Also living at number 25 were two

dressmakers, slipper makers, shoe makers, stay makers and a baker — in all 14 people

making up six families: one family to a room — so Mary’s financial situation, like

the area, had deteriorated. Neighbouring 29 Hanbury Street became infamous 30 years

later when the mutilated body of Annie Chapman was found by the doorway of the backyard;

she was the second victim of the serial killer who became known as ‘Jack the Ripper’.

A decade later in 1861, life had not altered greatly for mother and daughters, and

the three ladies were still living at Browns Lane, which was as crowded as before.

Mary and her daughters continued to support themselves, but by 1871, Mary, now in

her eighties, was unable to work and was suffering from the effects of old age to

the extent that her daughters could no longer care for her. As milliners, Mary Ann

and Ann Martha did piece work and were paid by the number of bonnets and hats they

produced or trimmings they sewed. It meant long days hunched over a needle or plating

straw. There was no alternative but for Mary to apply for admission to the workhouse.

She went to St George’s Workhouse in Princes Street, St George in the East, and was

an inmate there when the census was taken on 2 April 1871. On 17 June of that year,

Mary was admitted to the Infirmary suffering from ‘senility’. She remained in the

Workhouse for a further two years, dying on 4 July 1873 from ‘senile decay’. She

was 90 years old.

When Mary was born in about 1782 to Stephen and Ann Ducro, George III was on the

throne; Britain was at war, not with her old adversary, France, but with her most

troublesome colony, America; the Prime Minister, Lord North, had just stepped down

after a vote of no confidence; and the first convict ships would not leave Portsmouth

for Botany Bay for another five years.

When Mary was born in about 1782 to Stephen and Ann Ducro, George III was on the

throne; Britain was at war, not with her old adversary, France, but with her most

troublesome colony, America; the Prime Minister, Lord North, had just stepped down

after a vote of no confidence; and the first convict ships would not leave Portsmouth

for Botany Bay for another five years. Church. During this time,

Mary and her family were living at Crown Court, situated in the area behind Quaker,

Wheeler and Phoenix Streets.

Church. During this time,

Mary and her family were living at Crown Court, situated in the area behind Quaker,

Wheeler and Phoenix Streets. built the previous century and were single-

built the previous century and were single-