Early years

Little is known about Robert Cawt’s early life. He was probably born around 1765

in south London - there were Cawte’s living in the capital as early as the 1600s.

By 1789 he was living in the Parish of Newington St Mary, also known as Newington

Butts supposedly from the ancient butts for archery which once stood there, although

no evidence exists of this. Only a mile south of London Bridge, it had remained a

farming village with a low level of population until the second half of the eighteenth

century when the landowner, Henry Penton, began to sell of parcels of land for development.

New roads sprung up bringing development opportunities, although in 1802 Newington

consisted of only about 600 houses, many of which were small tenements in bad condition.

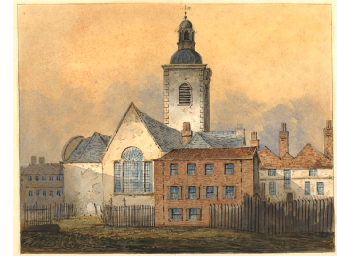

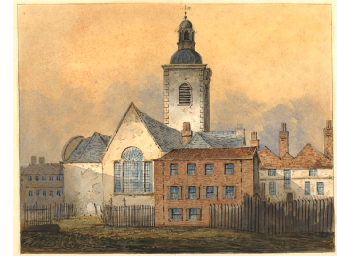

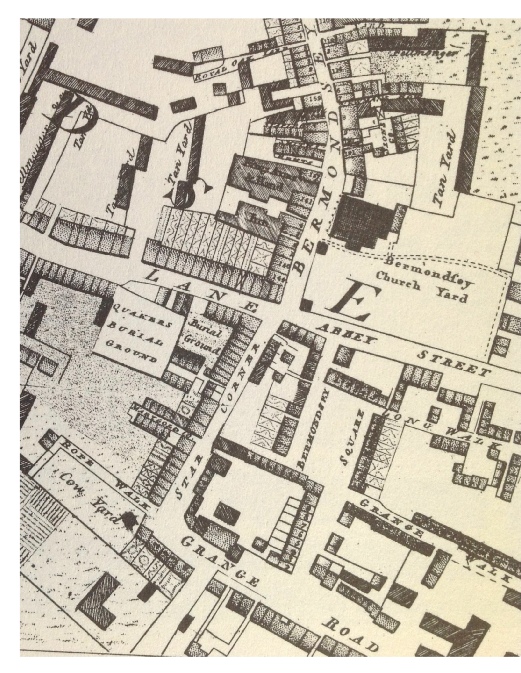

The map below shows the rural character of the area, and the illustration above shows

the main thoroughfare around 1800, with the spire of the Church of St Mary Newington

in the distance.

Little is known about Robert Cawt’s early life. He was probably born around 1765

in south London - there were Cawte’s living in the capital as early as the 1600s.

By 1789 he was living in the Parish of Newington St Mary, also known as Newington

Butts supposedly from the ancient butts for archery which once stood there, although

no evidence exists of this. Only a mile south of London Bridge, it had remained a

farming village with a low level of population until the second half of the eighteenth

century when the landowner, Henry Penton, began to sell of parcels of land for development.

New roads sprung up bringing development opportunities, although in 1802 Newington

consisted of only about 600 houses, many of which were small tenements in bad condition.

The map below shows the rural character of the area, and the illustration above shows

the main thoroughfare around 1800, with the spire of the Church of St Mary Newington

in the distance.

Family life

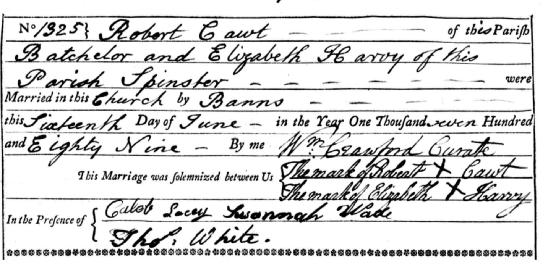

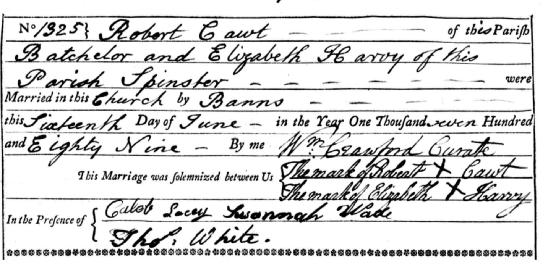

I t was at the Church of St Mary that Robert married Elizabeth Harvy on Tuesday 16

June 1789. It was a particular wet summer, with twice as much rain than usual from

May to July and the bride stepped warily through the London streets and the churchyard

in an attempt to keep her shoes and skirts clean. Once inside the church, bride and

groom made their mark, although the witnesses, of which there appear to be three

(Caleb Lacey, Susannah Wade and Thomas White, signed their names). At the time of

their marriage, Britain’s eyes were turned on events in France, and a month later,

news came from across the Channel that the citizens of Paris had stormed the Bastille.

t was at the Church of St Mary that Robert married Elizabeth Harvy on Tuesday 16

June 1789. It was a particular wet summer, with twice as much rain than usual from

May to July and the bride stepped warily through the London streets and the churchyard

in an attempt to keep her shoes and skirts clean. Once inside the church, bride and

groom made their mark, although the witnesses, of which there appear to be three

(Caleb Lacey, Susannah Wade and Thomas White, signed their names). At the time of

their marriage, Britain’s eyes were turned on events in France, and a month later,

news came from across the Channel that the citizens of Paris had stormed the Bastille.

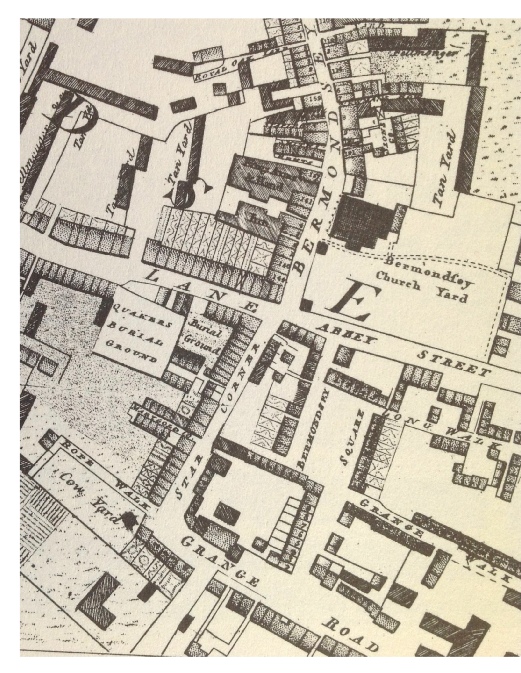

After their marriage, Robert and Elizabeth moved a mile or so east to Bermonsey which

was more densely populated with artisans and light industry, particularly tanning.

It was here that their first child, Richard, was born on 2 September 1792 and baptised

on 30 September�at the Church of St Mary in Bermondsey (shown above).  The baptism

entry records that Robert was a pin maker. Although this sometimes refers to the

pins that used in the pottery trade to support clay ware during firing, later evidence

shows that Robert was making sewing pins. Until the 1820s when steam powered, automatic

pin machines were designed, pins were hand-crafted. The most expensive part of the

manufacturing process was that of the brass wire, and the cost of wire drawing. The

many different sizes of pins produced r

The baptism

entry records that Robert was a pin maker. Although this sometimes refers to the

pins that used in the pottery trade to support clay ware during firing, later evidence

shows that Robert was making sewing pins. Until the 1820s when steam powered, automatic

pin machines were designed, pins were hand-crafted. The most expensive part of the

manufacturing process was that of the brass wire, and the cost of wire drawing. The

many different sizes of pins produced r equired the wire to be drawn down to many

different gauges. For the smallest pins this might need to be done through several

stages. Hand wire drawing required strength, skill and space. Even when part of the

process began to be automated, pin machines required large supply of wire. This wire

needed to be of a consistent quality throughout its length; something was difficult

to achieve by even the most skilled drawer using only a pair of pliers and his own

muscle power. At the time, Gloucester was the centre of pin making in Britain and

in 1802 there were nine factories in Gloucester employing 1,500 people (a fifth of

Gloucester’s population).

equired the wire to be drawn down to many

different gauges. For the smallest pins this might need to be done through several

stages. Hand wire drawing required strength, skill and space. Even when part of the

process began to be automated, pin machines required large supply of wire. This wire

needed to be of a consistent quality throughout its length; something was difficult

to achieve by even the most skilled drawer using only a pair of pliers and his own

muscle power. At the time, Gloucester was the centre of pin making in Britain and

in 1802 there were nine factories in Gloucester employing 1,500 people (a fifth of

Gloucester’s population).

At the time his first child was baptised, R obert and his family were living at Grange

Walk, a respectable street with houses dating from the late seventeenth and early

eighteenth century, as well as rows of newly built terraced houses for artisans.

The illustration on the left shows some of the more well-to-do houses; the map (left)

shows the area in about 1800. To the north of the Church are several tanneries and

at the end of Grange Road is a yard for cows which would have supplied fresh milk

to local residents. To the east and not shown on the map was a spa and gardens which

had opened in the 1770s.

obert and his family were living at Grange

Walk, a respectable street with houses dating from the late seventeenth and early

eighteenth century, as well as rows of newly built terraced houses for artisans.

The illustration on the left shows some of the more well-to-do houses; the map (left)

shows the area in about 1800. To the north of the Church are several tanneries and

at the end of Grange Road is a yard for cows which would have supplied fresh milk

to local residents. To the east and not shown on the map was a spa and gardens which

had opened in the 1770s.

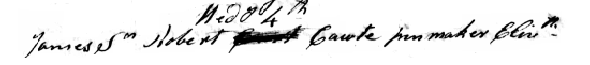

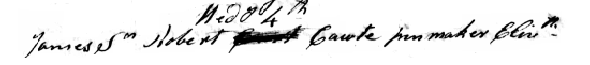

By 1798, Robert and his family had moved a little to the north-west, towards the

river and Southwark, where another son, James, was born. He was baptised at the Church

of St Saviour and the register (pictured below) shows that James continued to work

as a pin maker. The register also shows that the spelling of the Cawte name was corrected,

which would suggest that James could perhaps read and spell his name even if he could

not write; it was not uncommon for people to be able to read but not write, since

for the working classes, writing was considered necessary only for those who needed

the skill for their work.

Three years later on 30 September 1798, Elizabeth gave birth to a son, William Robert.

Another child, Elizabeth Ann, was born in 1801 and baptised at the Church of St Saviour

in Southwark. Robert’s occupation was shown as ‘wire drawer’, i ndicating that he

had advanced from making pins from drawn wire to the more skilled process of drawing

the wire itself.

ndicating that he

had advanced from making pins from drawn wire to the more skilled process of drawing

the wire itself.

Nothing more is know of Robert after 1801 and details of his death have not been

found. Elizabeth survived until 1838, so the fact that no more children are recorded

after 1801 may indicate that Robert died in the early 1800s.

Little is known about Robert Cawt’s early life. He was probably born around 1765

in south London -

Little is known about Robert Cawt’s early life. He was probably born around 1765

in south London -

t was at the Church of St Mary that Robert married Elizabeth Harvy on Tuesday 16

June 1789. It was a particular wet summer, with twice as much rain than usual from

May to July and the bride stepped warily through the London streets and the churchyard

in an attempt to keep her shoes and skirts clean. Once inside the church, bride and

groom made their mark, although the witnesses, of which there appear to be three

(Caleb Lacey, Susannah Wade and Thomas White, signed their names). At the time of

their marriage, Britain’s eyes were turned on events in France, and a month later,

news came from across the Channel that the citizens of Paris had stormed the Bastille.

t was at the Church of St Mary that Robert married Elizabeth Harvy on Tuesday 16

June 1789. It was a particular wet summer, with twice as much rain than usual from

May to July and the bride stepped warily through the London streets and the churchyard

in an attempt to keep her shoes and skirts clean. Once inside the church, bride and

groom made their mark, although the witnesses, of which there appear to be three

(Caleb Lacey, Susannah Wade and Thomas White, signed their names). At the time of

their marriage, Britain’s eyes were turned on events in France, and a month later,

news came from across the Channel that the citizens of Paris had stormed the Bastille. The baptism

entry records that Robert was a pin maker. Although this sometimes refers to the

pins that used in the pottery trade to support clay ware during firing, later evidence

shows that Robert was making sewing pins. Until the 1820s when steam powered, automatic

pin machines were designed, pins were hand-

The baptism

entry records that Robert was a pin maker. Although this sometimes refers to the

pins that used in the pottery trade to support clay ware during firing, later evidence

shows that Robert was making sewing pins. Until the 1820s when steam powered, automatic

pin machines were designed, pins were hand- equired the wire to be drawn down to many

different gauges. For the smallest pins this might need to be done through several

stages. Hand wire drawing required strength, skill and space. Even when part of the

process began to be automated, pin machines required large supply of wire. This wire

needed to be of a consistent quality throughout its length; something was difficult

to achieve by even the most skilled drawer using only a pair of pliers and his own

muscle power. At the time, Gloucester was the centre of pin making in Britain and

in 1802 there were nine factories in Gloucester employing 1,500 people (a fifth of

Gloucester’s population).

equired the wire to be drawn down to many

different gauges. For the smallest pins this might need to be done through several

stages. Hand wire drawing required strength, skill and space. Even when part of the

process began to be automated, pin machines required large supply of wire. This wire

needed to be of a consistent quality throughout its length; something was difficult

to achieve by even the most skilled drawer using only a pair of pliers and his own

muscle power. At the time, Gloucester was the centre of pin making in Britain and

in 1802 there were nine factories in Gloucester employing 1,500 people (a fifth of

Gloucester’s population). obert and his family were living at Grange

Walk, a respectable street with houses dating from the late seventeenth and early

eighteenth century, as well as rows of newly built terraced houses for artisans.

The illustration on the left shows some of the more well-

obert and his family were living at Grange

Walk, a respectable street with houses dating from the late seventeenth and early

eighteenth century, as well as rows of newly built terraced houses for artisans.

The illustration on the left shows some of the more well- ndicating that he

had advanced from making pins from drawn wire to the more skilled process of drawing

the wire itself.

ndicating that he

had advanced from making pins from drawn wire to the more skilled process of drawing

the wire itself.