james bostock (1798-

Early years

James was born on Wednesday 6 June 1798 in Putney during a time of great unrest:

England had been at war with France for five years, mutinies in the Royal Navy over

pay and conditions had triggered fears of a French-

James was born on Wednesday 6 June 1798 in Putney during a time of great unrest:

England had been at war with France for five years, mutinies in the Royal Navy over

pay and conditions had triggered fears of a French-

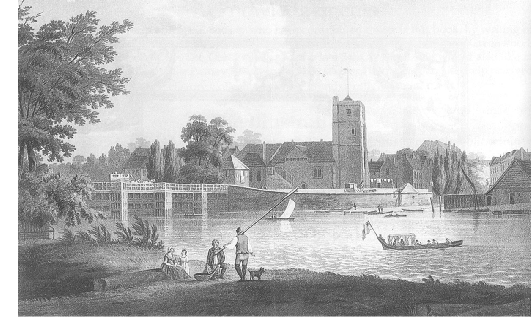

The Spring of 1798 was warm and fine and seven weeks James’ birth, on Wednesday 25 July, James’s parents, James and Elizabeth, walked to the medieval Church of St Mary beside the river where they baptised him, just as they had done with his sister, Sarah, three years earlier. It was a brief affair, the text of the christening sermon mingling with the rumble of carts and carriages proceeding to the Fulham Bridge and the cries of the watermen plying their trade on the river. About a year later, in October 1799, James and Elizabeth returned to the church to bury their daughter, Sarah.

New horizons

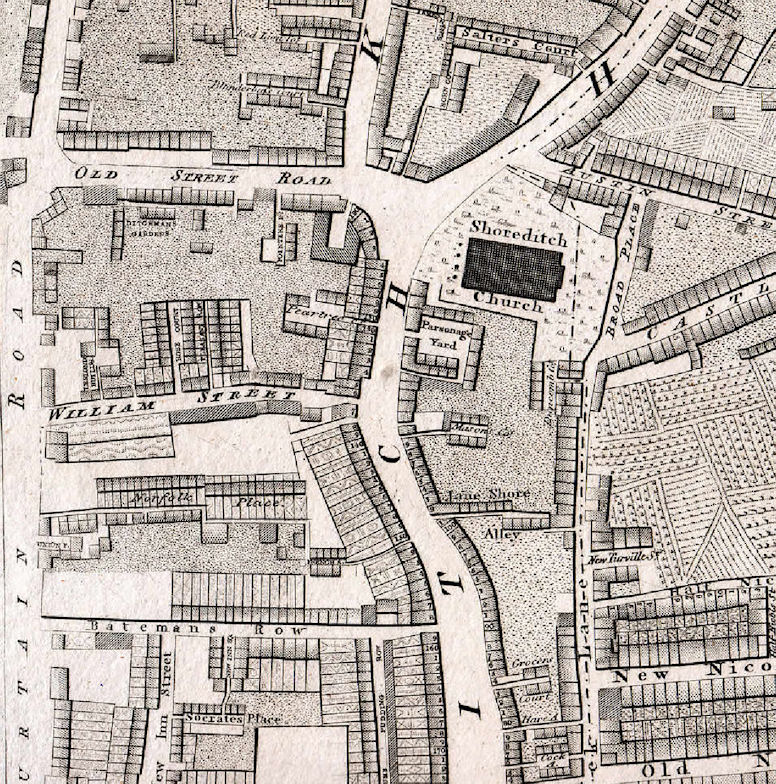

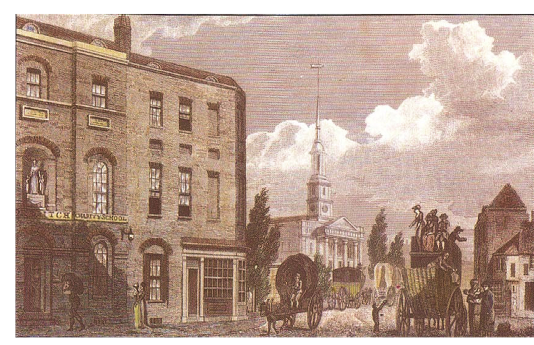

Putney was a pleasant, healthy place to grow up, but its building boom was over and James’ father, as a carpenter, was looking for new opportunities. Some time between 1800 and 1808, James and his family relocated to the east of the City and the north side of the river to Shoreditch.

At the turn of the nineteenth century, Shoreditch marked the eastern limits of the

urban sprawl; the Hackney Road stretched eastwards from the Church of St Leonard,

the rows of houses giving way to gardens, orchards and fields. But Shoreditch was

changing rapidly and in the years from 1801 to 1830 the population doubled from 35,000

to around 70,000, a growth unsurpassed by any other parish in London, making it an

ideal spot for a carpenter. Living in Shoreditch at this time were William and Susannah

Bostock. William was born around 1795 and was a plasterer by trade; he was most likely

related to James, and may have been James’ brother. Certainly, when it was time for

James to learn a trade, rather than following in his father’s footsteps, James was

apprenticed as a stenciller and a plasterer. It is also interesting to note that

in 1805-

Learning a trade

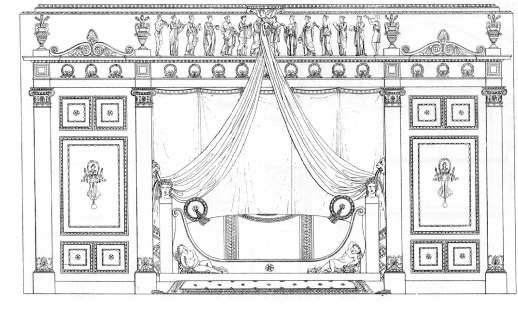

During the Regency period, plastering and stencilling enjoyed a huge revival and

achieved a level of skill unsurpassed either before or since. Rooms were decorated

with elaborate schemes based on classical antiquity and plaster mouldings were produced

in all shapes and sizes: acanthus leaves, Grecian pillars and capitals, urns, cornucopias

and griffons. These intricate mouldings were combined with stencilled designs, with

walls being either stencilled directly or covered with lengths of decorated wallpaper.

Many studios kept catalogues of designs so prospective buyers could combine various

motifs to suit their taste and thus eliminate “the monotony presented by most rooms,

which offer the eye nothing but empty panels”. The neo-

During the Regency period, plastering and stencilling enjoyed a huge revival and

achieved a level of skill unsurpassed either before or since. Rooms were decorated

with elaborate schemes based on classical antiquity and plaster mouldings were produced

in all shapes and sizes: acanthus leaves, Grecian pillars and capitals, urns, cornucopias

and griffons. These intricate mouldings were combined with stencilled designs, with

walls being either stencilled directly or covered with lengths of decorated wallpaper.

Many studios kept catalogues of designs so prospective buyers could combine various

motifs to suit their taste and thus eliminate “the monotony presented by most rooms,

which offer the eye nothing but empty panels”. The neo-

Decorative plaster mouldings were usually cast in a workshop and then assembled and

installed in the building. James learnt how to mix the plaster and cast the mouldings

before installing them. The process required the skills of a mason, a carpenter and

a plasterer, making the Bostock family well- .

.

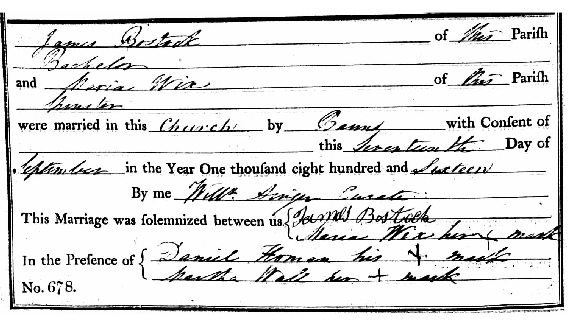

Not long after he had learnt his trade, and still only 18, James married. Marie Antoinette

Wicks had been born and bred in Shoreditch and she and James were probably neighbours.

On Tuesday 17 September 1816, they walked down the avenue of elm and horse chestnut

trees to stand before the stained glass window recently installed in the east window

behind the altar of the Church of St John in Hackney (pictured below). The marriage

was witnessed by Daniel Homan (Marie Antoinette’s brother-

Many children in the eighteenth and nineteenth century could read by the age of seven

or eight, but writing was seen as a vocational and primarily male skill usually taught

by male tutors who also taught arithmetic and other basic business or trade skills:

throughout the eighteenth and much of the nineteenth centuries, very few children

had  learned to write by the age of seven or eight. That James could read and write

indicates that James’ parents were educated themselves, had an income sufficient

to give him a basic education, and did not require him to go out to work from a young

age -

learned to write by the age of seven or eight. That James could read and write

indicates that James’ parents were educated themselves, had an income sufficient

to give him a basic education, and did not require him to go out to work from a young

age -

The marriage register also shows that before his own marriage, James acted as a witness for William Donaldson and Elizabeth Marshall. They may have been friends, but it is just as likely that James stepped in to act as a witness while waiting to be married himself. It is the act of a confident young man.

Married life

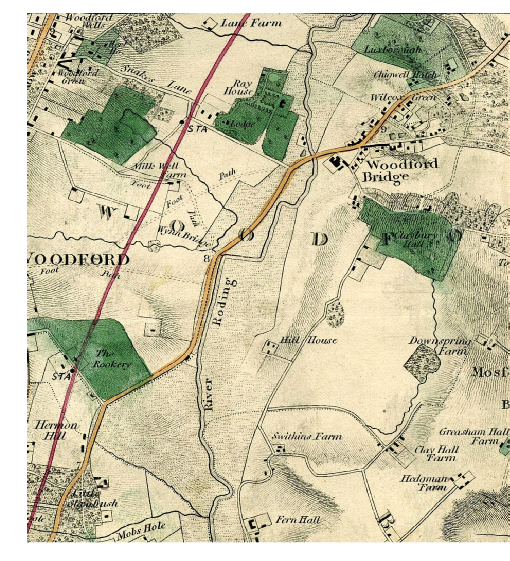

A year after their marriage, James and Maria were living at Cock Lane (the road is shown on the bottom right of the map running up towards the St Leonard’s church). This ran parallel to the main Shoreditch Road up to the Church of St Leonard. In later years, it was one of the roads that bordered an area that became known as the ‘Old Nichol’, but in 1816 it was still a respectable neighbourhood of artisans. It was here that James’s son was born. As was the custom, he was named after his father (and grandfather). Another son, George, was born the following year.

The years that followed present something of a vacuum. No other children are known to have been born until about May 1830 when another son was born. He was baptised at the Church of St Leonard and called James, indicating that James and Marie Antoinette’s eldest son had died in the intervening years. James and his family were living in Hackney Road, a step up from Cock Lane.

‘When I grow rich’

James was a confident, intelligent young man with an entrepreneurial spirit, and he took full advantage of the building boom. By his late twenties, he had done well enough to be managing his own plastering workshop and stencilling studio; the term ‘decorator’ which he often used to describe himself on official documents was a true if somewhat humble description of his occupation.

An astute business man, he invested in property. The area north and east of the Hackney

Road was developing rapidly, the green spaces between the villages of Hackney, Bethnal

Green a nd Stepney filling in with rows of houses and light industry. By the time

James was in this thirties, he owned or had an interest in numbers 5 and 11 Hackney

Road, and three other properties north of the Hackney Road: Tuillerie Street, 2 Pritchard’s

Place, and 3 Maidstone Street. When he heard the bells of St Leonard’s Church ring

out, one wonders if he ever thought of the children’s rhyme ‘Oranges and Lemons’

which proclaimed, ‘When I grow rich say the bells of Shoreditch, When will that be

say the bells of Stepney. I’m sure I don’t know says the great bell of Bow’.

nd Stepney filling in with rows of houses and light industry. By the time

James was in this thirties, he owned or had an interest in numbers 5 and 11 Hackney

Road, and three other properties north of the Hackney Road: Tuillerie Street, 2 Pritchard’s

Place, and 3 Maidstone Street. When he heard the bells of St Leonard’s Church ring

out, one wonders if he ever thought of the children’s rhyme ‘Oranges and Lemons’

which proclaimed, ‘When I grow rich say the bells of Shoreditch, When will that be

say the bells of Stepney. I’m sure I don’t know says the great bell of Bow’.

But whilst James’ business prospered, all was not well at home. He may have remained

with Marie Antoinette long enough to see his son baptised, but by the Autumn of 1830

James was in a relationship with the ‘lovely’ Sarah Homan -

The lovely Sarah

Sarah was born in Shoreditch in 1803, the eldest child of Daniel Homan and Mary Wicks (Wix). Her father was a shoemaker or cordwainer who was born in Shoreditch in 1780, living there until he died in 1857. The Bostock and Wicks families had close ties and Daniel had been a witness at James and Maria Antoinette’s wedding.

In an era before divorce, relationships outside of marriage were not uncommon, particularly

amongst the working class, but to leave one’s wife for perhaps a niece or a s econd

cousin, when the families lived in such close proximity, was a bold step. James and

Marie Antoinette’s marriage must have been very unhappy, and the mutual attraction

-

econd

cousin, when the families lived in such close proximity, was a bold step. James and

Marie Antoinette’s marriage must have been very unhappy, and the mutual attraction

-

James and Sarah’s first child, William Homan, was born on 11 June 1831. To avoid gossip, disapproving looks from their neighbours and perhaps an awkward scene in church with Marie Antoinette, one Sunday a month after his birth, James and Sarah travelled the few miles across London to the Church of St Mary in Islington where they had William baptised. They presented themselves as ‘James and Sarah Bostock’ and gave their place of abode as ‘High Street’.

James continued to live with Sarah in Shoreditch, finding with her the domestic happiness

that had eluded him with  Marie Antoinette. Over the next 10 years, Sarah bore four

more children: Edward (1834), Sarah (1836), Maria (1840), and Thomas (1841). Whatever

their families thought of their domestic arrangements, they remained close, and in

1841 James and Sarah were living at 3 Maidstone Street next door to Sarah’s brother

and sister-

Marie Antoinette. Over the next 10 years, Sarah bore four

more children: Edward (1834), Sarah (1836), Maria (1840), and Thomas (1841). Whatever

their families thought of their domestic arrangements, they remained close, and in

1841 James and Sarah were living at 3 Maidstone Street next door to Sarah’s brother

and sister-

By 1851, James, Sarah and their six children (John had been born in 1849) had moved to 2 Pritchard’s Place in Hackney. James gave his occupation as a ‘plasterer and decorator’ and Sarah Homan as ‘housekeeper’ with ‘no relationship’ to James. His business continued to flourish with at least one plaster workshop and a number of properties.

With the profits from his business and rents from his properties, James was able to rent a cottage outside of the City in Woodford in Essex. A Post Office Directory of 1862 describes Woodford as, ‘...most salubrious and the facility with which it may be reached has caused it to be the suburban residence of many merchants… the village is picturesquely seated with many fine views’. The facility to which the quote refers was the railway, which reached Woodford in 1856 and made it ideally situated: close enough to James’ business interests in Shoreditch and Hackney, but far enough removed to provide a pleasant countryside environment for James and his family.

Dividing the spoils

Dividing the spoils

If James’ idea was to enjoy his retirement and his hard-

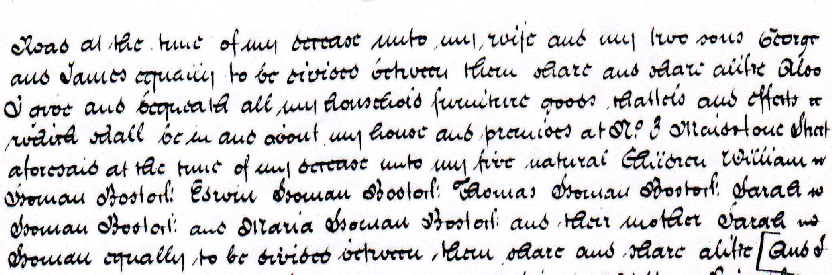

James’ Will, made in 1844, reveals an astute business-

Under the terms of his Will, Marie Antoinette and his two legitimate sons, George and James, were to receive the content of 5 Hackney Road. The content of 3 Maidstone Street was left to Sarah Homan and James’ natural children by her. His remaining property was left in trust to his friends, William Reid and William Dudderidge, for them to share the profits and rents amongst James’ beneficiaries (that is, Marie Antoinette, George, James, Sarah, and James’ children by Sarah). The remainder of his estate, James left to the younger of his two legitimate sons, James. By a Codicil of 1853, James added John Homan Bostock (who had been born in 1853) to his list of beneficiaries. By a twist of fate, 11 days after this Codicil, James’ legitimate son, George, was dead, leaving his brother James the only legitimate heir.

William Dudderidge and William Reid were well-

William Dudderidge and William Reid were well-

After James’s death, his eldest son, James, lived at 2 Pritchard’s Place with his family. However, he did not enjoy his inheritance for long, dying on 14 October 1866 of apoplexy (probably a stroke). His own estate was valued at under £200 (about £8,000 in today’s terms). On 27 November, probate was granted on his estate which went to his widow, Mary Ann.

The two widows

After James’ death, Sarah, James’ widow in all but law, lived with her son, Thomas, in South Hackney at 4 Elizabeth Terrace, and in the 1861 census described herself as a ‘house proprietor’ and as ‘Sarah Bostock’. She died suddenly on 31 January 1867, resulting in a post mortem and a Coroner’s inquest. The cause of death is given on the death certificate as ‘sudden disease of heart’ so presumably the inquest returned a verdict of death by natural causes.

Marie Antoinette continued to live at 11 Hackney Road and was listed in the 1861 as ‘proprietress of house’; living with her were three of her grandchildren: James George, Edwin Francis and Ann Martha. A decade later, her grandchildren grown up, Marie Antoinette was living at 12 Carlew Road in Bethnal Green. Presumably she rented the house which she lived in on her own and was described as an ‘annuitant’. Two years later she was either visiting or had moved in with her daughter, Marie Antoinette Villiers, who lived at She died two years later on 23 August 1873 at 7 Camden Cottages, Lower Sydenham. On 21 August Marie Antoinette suffered a stroke. She died two days later.

james bostock

(1798-

may alexandra bostock

(1911-

marie antoinette wicks

m

who’s related to whom

living moss

(born 1947)

living moss

(born 1968)

james bostock

(circa 1770)

| paternal tree |

| maternal tree |

| index of names |

| monger photos |

| moss photos |

| collins photos |

| bostock photos |

| george moss |

| william moss |

| george c moss |

| eleanor evans |

| gregory family |

| thomas gregory |

| thomas gregory |

| sissey family |

| christopher sissey |

| sissey children |

| brisco family |

| william briscoe |

| john biscoe |

| susan webb |

| briscoe children |

| betsy biscoe |

| james bostock |

| george bostock |

| james g bostock |

| edwin f bostock |

| may bostock |

| marie wicks & sarah homan |

| homan bostock family |

| steward family |

| charles steward |

| ducro family |

| esther steward |

| mary & ann steward |

| stephen ducro |

| mary ducro |

| Ann_Briggs |

| hockerday family |

| thomas hockaday |

| mary ann hockerday |

| peters family |

| william peters |

| joseph peters |

| emily a peters |

| joseph collins |

| samuel collins |

| joseph collins |

| henry j collins |

| florence a collins |

| william shepherd |

| ann e shepherd |

| rogers family |

| john rogers |

| sarah a rogers |

| harvey family |

| thomas harvey |

| ann harvey |

| grigg family |

| william monger |

| charles monger |

| george monger |

| albert j monger |

| benham family |

| thomas benham |

| mary a benham |

| stephen dunford |

| fanny dunford |

| cawte family |

| robert cawte |

| william cawte |

| john r cawte |

| reynolds family |

| william reynolds |

| emma reynolds |