Early years

Ann Harvey was born in about 1823 near Tipton in the West Midlands, the daughter

of Thomas Harvey and Sarah Grigg. It was here that she was baptised on 2 November

1823, although her elder and younger siblings were all baptised in Oldbury, less

than three miles away.

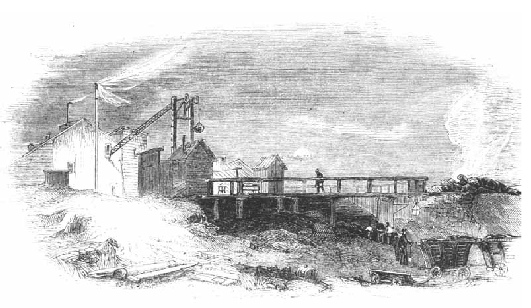

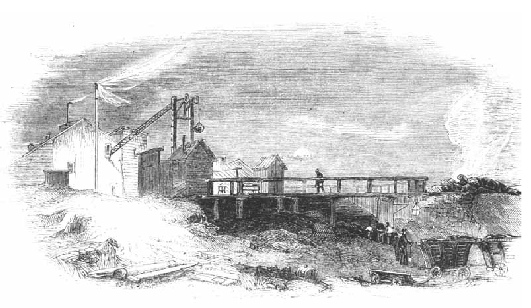

Her father and uncles were miners and it is probable  that Ann worked at the coal

face from a young age, if not down the mines. Before the Mines Act of 1842 which

prohibited females and boys under ten from working underground, it was not uncommon

for children of either sex to work down the mine. Whether or not Ann was employed

at the mine, life was one of hard physical labour from a young age. With one in every

two children dying before the age of three, only the strongest infants survived,

and eye-witness accounts comment on the health and robustness of the women of mining

families (the photograph below shows five ‘pit brow lasses’, the name given to women

who worked in the Lancashire collieries). One amusing account (Osborne's Guide to

the Grand Junction Railway, 1838) noted:

that Ann worked at the coal

face from a young age, if not down the mines. Before the Mines Act of 1842 which

prohibited females and boys under ten from working underground, it was not uncommon

for children of either sex to work down the mine. Whether or not Ann was employed

at the mine, life was one of hard physical labour from a young age. With one in every

two children dying before the age of three, only the strongest infants survived,

and eye-witness accounts comment on the health and robustness of the women of mining

families (the photograph below shows five ‘pit brow lasses’, the name given to women

who worked in the Lancashire collieries). One amusing account (Osborne's Guide to

the Grand Junction Railway, 1838) noted:

“The women in this neighbourhood seldom wear caps. They mostly use a handkerchief

tied round their head, and neither in person or manner show much of grace, or attraction.

They are early used to carry heavy burdens, and help to load and unload at the mouth

of the pit; hence they become coarse and unwieldy, and lose that natural pleasantness,

if not gracefulness of appearance, which is common to their sex. This is particularly

observable in the extreme width of their mouths, shortness of the necks, and breadth

of their shoulders, caused by the habit of carrying heavy baskets of coal on their

heads from the shafts of the pits to their respective dwellings, there being a regular

allowance to each workman for his individual home consumption.”

Married life

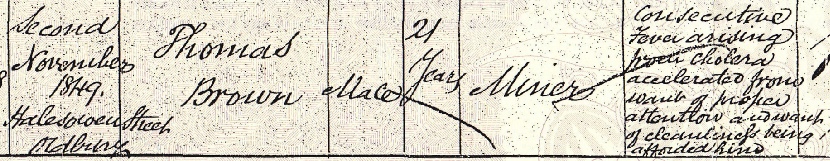

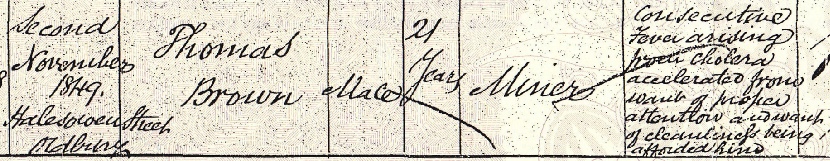

Whatever her appearance, Ann had found a husband by 1846.  Unsurprisingly, Thomas

Brown was a miner. They were married on 24 August 1846 at Christ Church in Stourbridge.

Their daughter Betsy was born on 12 July 1849 at Halesowen Road. Four months later,

Thomas died, leaving Ann a young widow with an infant child. Thomas’s early death

would suggest a mining accident, but his death certificate revels another story,

with the cause of death as cholera.

Unsurprisingly, Thomas

Brown was a miner. They were married on 24 August 1846 at Christ Church in Stourbridge.

Their daughter Betsy was born on 12 July 1849 at Halesowen Road. Four months later,

Thomas died, leaving Ann a young widow with an infant child. Thomas’s early death

would suggest a mining accident, but his death certificate revels another story,

with the cause of death as cholera.

Cholera first appeared in Europe in the early 1830s, believed to have been brought

from India. It causes severe cramps and rapid dehydration through vomiting and diarrhoea

and death can occur within hours and was thought to be local miasmatic disease, brought

about by exposure to filth and decay. But Thomas’ death certificate states that his

demise was due not only to cholera but also to a lack of care: ‘consecutive fever

arising from cholera accelerated from want of proper attention and cleanliness being

afforded him’. Whilst it may reflect the facts, it is a harsh statement given the

unsanitary conditions and lack of washing facilities in many working-class homes.

Ironically, achieving ‘greater cleanliness’ would have involved using water which

may have been infected with cholera, not only doing nothing to relieve the symptoms

but putting Ann and her four-month old daughter at risk. It was not until 1855,

six years after Thomas’ death, that scientists discovered that cholera was water-borne.

On the move

After her husband’s death, Ann returned to live with her parents. The following year

on 21 June 1852, still only 29 years old, she married for the second time. John Rogers

was a labourer from the area, so it may have been something of a step down for Ann,

since miners were far better paid than those who laboured above ground. But being

seven months pregnant, Ann could no longer afford to be choosy. Their son was was

born on 16 August and baptised Thomas; conveniently, it was the name of both Ann’s

father and her dead husband.

Over the next twenty or so years, Ann travelled the length and breadth of the country

with John as he moved from brickfield to brickfield in search of work: Kirkby Lonsdale

in Westmoreland, Burton-on-Trent, London, and Barrow-in-Furness were just some of

the locations where they settled, and were Ann bore seven more children. The family

stayed generally no more than a year or two in each location. Unable to draw on the

support of family, and barely in one place long enough to make friends that she could

call on in times of trouble, Ann’s was not an easy life, although the family returned

to Oldbury between jobs.

After Ann’s husband, John, died sometime between 1871 and 1881, Ann continued to

travel with her youngest daughter, Sarah Ann, and her son Thomas and daughter-in-law,

Ann. After Sarah Ann married in 1889, Ann spent the rest of her life with her daughter

and son-in-law, and their ever-expanding family. She died some time between 1901

and 1911.

that Ann worked at the coal

face from a young age, if not down the mines. Before the Mines Act of 1842 which

prohibited females and boys under ten from working underground, it was not uncommon

for children of either sex to work down the mine. Whether or not Ann was employed

at the mine, life was one of hard physical labour from a young age. With one in every

two children dying before the age of three, only the strongest infants survived,

and eye-

that Ann worked at the coal

face from a young age, if not down the mines. Before the Mines Act of 1842 which

prohibited females and boys under ten from working underground, it was not uncommon

for children of either sex to work down the mine. Whether or not Ann was employed

at the mine, life was one of hard physical labour from a young age. With one in every

two children dying before the age of three, only the strongest infants survived,

and eye- Unsurprisingly, Thomas

Brown was a miner. They were married on 24 August 1846 at Christ Church in Stourbridge.

Their daughter Betsy was born on 12 July 1849 at Halesowen Road. Four months later,

Thomas died, leaving Ann a young widow with an infant child. Thomas’s early death

would suggest a mining accident, but his death certificate revels another story,

with the cause of death as cholera.

Unsurprisingly, Thomas

Brown was a miner. They were married on 24 August 1846 at Christ Church in Stourbridge.

Their daughter Betsy was born on 12 July 1849 at Halesowen Road. Four months later,

Thomas died, leaving Ann a young widow with an infant child. Thomas’s early death

would suggest a mining accident, but his death certificate revels another story,

with the cause of death as cholera.