Early years

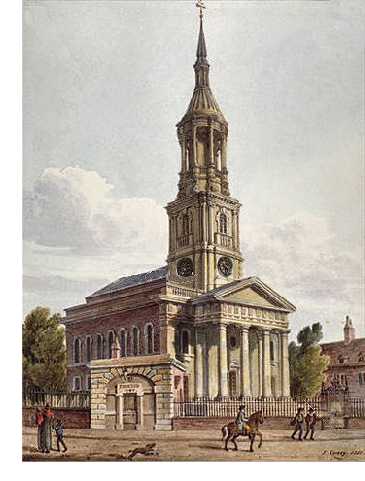

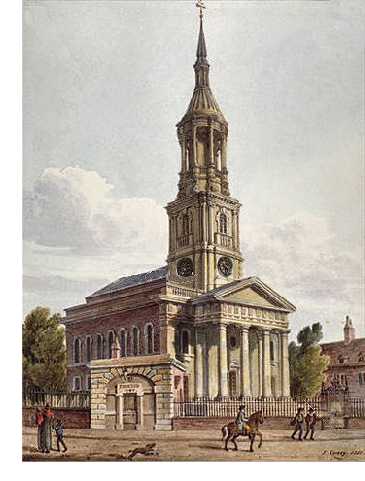

George was born on 21 November 1818 in Holywell Lane, Shoreditch, the second child

of James Bostock and Marie Antoinette Wicks (Wix). A few weeks later, like so many

of the Bostock infants, he was baptised at the Church of St Leonard, although his

surname was entered into the baptism register incorrectly as ‘Boaster’. The church

is shown in the illustration on the right at about the same time of George’s baptism.

George was born on 21 November 1818 in Holywell Lane, Shoreditch, the second child

of James Bostock and Marie Antoinette Wicks (Wix). A few weeks later, like so many

of the Bostock infants, he was baptised at the Church of St Leonard, although his

surname was entered into the baptism register incorrectly as ‘Boaster’. The church

is shown in the illustration on the right at about the same time of George’s baptism.

At the time of his birth, Shoreditch and the Hackney Road, like much of England,

were in a state of transformation: there were still watercress beds by Hackney brook

and London was connected by a stagecoach link which ran from Bishopsgate. But many

of the seventeenth century mansions were being converted for use as almshouses, private

schools and charitable institutions, such as the villa acquired by the British Penitent

Female Refuge to reclaim and resettle prostitutes. The completion of the Regents

Canal in 1820 signalled the real beginnings of change, confirmed by the inauguration

of the omnibus service in 1838 and the construction of the North London Railway in

the 1850s.

George’s father was bright and ambitious, and he seized the opportunities such growth

presented. Financially, he was doing well and the young George did not lack the necessities

of life, including a basic education which meant he was able to read and write. What

he did lack was a peaceful and loving home. His parent’s marriage was not a happy

one, and his father’s business occupied much of his time. When George’s elder brother,

James, died some time between 1818 and 1830, George was left an only child with a

near-absent father and a sharp-tongued mother.

In May 1830, twelve years after George’s birth, his mother gave birth to another

child, who was baptised, James. ‘Recycling’ names of dead children to ensure a family

named lived on - in this case George’s father’s name - was common and would not have

been seen as at all morbid. By the arrival of his sibling, his parents’ marriage

had broken down and George’s father left his family to live with his wife’s relative

(probably a niece or cousin), Sarah Homan.

James senior continued to take care of his family financially, and as soon as he

was old enough, George began working in his father’s business; over the years, George

described his occupation variously as stenciller, paper hanger and plasterer.

A new chapter

It was a difficult time for young George, living with his mother, yet working with

his father and seeing him set up home and raise a family with one of his Homan relatives.

The two families also lived in close proximity which only added to the tension.

But life goes on, and by the time George had learnt his trade, he had met Esther

Steward. She was from a respectable family of artisans who had lived in Spitalfields

for almost a hundred years. Her father, Charles, was a carpenter and may have been

a business acquaintance of the Bostock family. George and Esther were married on

29 September 1839 at the Church of St John in Hackney, the same church where George’s

parents had married in 1816. They were both living in nearby Mare Street at the time.

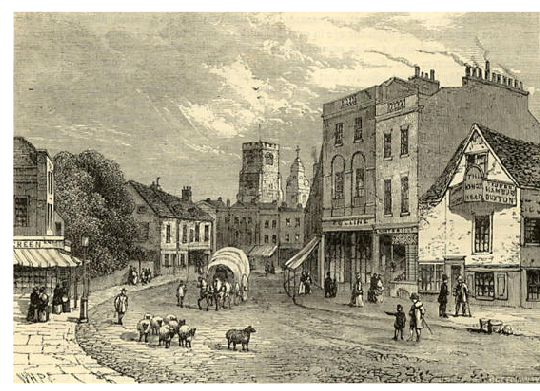

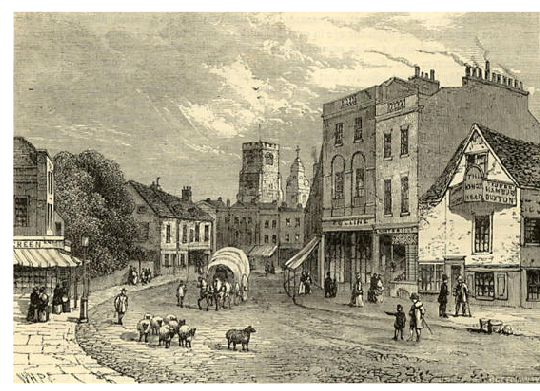

The engraving below shows Mare Street in about 1840 looking towards the Church of

St John (both locations are shown on the the map of 1837 above: Mare Street running

up from the bottom of the map, and ‘Hackney Church’ at the top of the map).

After their marriage, George and Esther moved to his mother’s home at 5 Hackney Road.

The ground floor was most likely a shop or workshop; another floor was rented out,

leaving the Bostock family another floor of two rooms to live in. The photograph

below was taken in May 2012 and, whilst numbering has changed since the 1800s, the

building shown with the yellow-framed windows was probably numbers 4 and 5 or 5 and

6.  It was here that George and Esther’s first child, George Rowland, was born on

29 November 1840. A month later, on Christmas day, George and Esther walked the short

distance to Church of St Leonard to baptise him. The Church, which stands at the

junction of the Hackney and Kingsland Roads, was a visible and integral part of their

lives; its chimes meant that they needed no clock.

It was here that George and Esther’s first child, George Rowland, was born on

29 November 1840. A month later, on Christmas day, George and Esther walked the short

distance to Church of St Leonard to baptise him. The Church, which stands at the

junction of the Hackney and Kingsland Roads, was a visible and integral part of their

lives; its chimes meant that they needed no clock.

In January 1842, George Rowland contracted whooping cough, a highly contagious disease

which, together with measles, was one of the main causes of infant death in the mid-nineteenth

century: between 1838 and 1840, 50,000 children died of these illnesses in Britain.

George Rowland died on Friday 4 February, although it was not until Sunday 13 February

1842, that George and Esther walked the short distance to the churchyard of St Leonard’s

to bury him. In the days before mortuaries and refrigeration, nine days between death

and burial appears a long time, but it was not uncommon and, since the family were

by no means poor, it is likely that burial waited until the next available Sunday.

A report by Dr John Simon, from the City of London, in 1852 expresses anxiety over

this practice:

“... the prolonged keeping of dead bodies in the rooms of their living kindred ...

in the poor man’s dwelling. The sides of a wooden coffin, often imperfectly joined,

are at best all that divides the decomposition of the dead from the respiration of

the living. A room, tenanted night and day by the family of mourners, likewise contains

the remains of the dead. For some days the coffin is unclosed. The bare corpse lies

there amid the living; beside them in their sleep; before them at their meals. Death

perhaps has occurred on a Wednesday or Thursday; the next Sunday is thought too early

for the funeral; the body remains unburied till the Sunday week. Summer or winter

makes little difference to this detention”.

Later that year, Esther became pregnant, giving birth to a daughter in May 1842.

She was named Marie Antoinette after George’s mother, and was baptised on Sunday,

21 May 1843 at the Church of St Leonard. Probably unbeknownst to George, in 1844

his father, James, made his Will. The Will was at great pains to divide everything

equally between James’ wife, legitimate children, common-law-wife, and his natural

children; they were to receive an equal share of the rents and profits from his properties,

and each family the contents on one of his properties. However, James bequeathed

the residue of his estate to his younger son, James. Perhaps James felt that his

younger son would be in greater need of his father’s assistance; it may also indicate

an unsteadiness of character on George’s part, or a rift between father and son.

Given the circumstances of George’s upbringing, it would not be surprising.

Later that year, Esther became pregnant, giving birth to a daughter in May 1842.

She was named Marie Antoinette after George’s mother, and was baptised on Sunday,

21 May 1843 at the Church of St Leonard. Probably unbeknownst to George, in 1844

his father, James, made his Will. The Will was at great pains to divide everything

equally between James’ wife, legitimate children, common-law-wife, and his natural

children; they were to receive an equal share of the rents and profits from his properties,

and each family the contents on one of his properties. However, James bequeathed

the residue of his estate to his younger son, James. Perhaps James felt that his

younger son would be in greater need of his father’s assistance; it may also indicate

an unsteadiness of character on George’s part, or a rift between father and son.

Given the circumstances of George’s upbringing, it would not be surprising.

Married life

For George, life carried on in much the same way, the everyday routine punctuated

by more significant events, more often than not the birth of a child: Ann Martha

(January 1845), James George (January 1847), Frederick William (January 1849), and

Charles Edward (December 1850), all of whom were baptised at the Church of St Leonard.

As well as births, there were also the inevitable deaths. On the morning of Tuesday,

18 February 1851, George and Esther awoke to find their 13-week old son, Charles

Edward, dead. Although such events were not uncommon, an inquest was held. In an

era before the term ‘cot death’ had been coined, the death certificate recorded the

cause as simply ‘found dead in bed without marks of violence’. Charles was buried

on Sunday 23 February.

Later that year, Esther found herself expecting what would be her last child. On

31 May 1852, she gave birth to a boy who was baptised Edwin Francis; it was a name

that would reoccur in the Bostock history for the next four generations.

The last journey to the Church of St John

A year and a half later on 11 December 1853, George died at 5 Hackney Road; he was

just 35 years old. The doctor recorded the cause of death as ‘syrosis — two weeks’

(sic). The two most common causes of cirrhosis are alcohol and hepatitis. Given the

difficulties between George’s parents and the evidence of his father’s Will, the

natural conclusion is that George drunk himself into an early grave. Unusually, he

was not buried in the churchyard of St Leonard’s, where two of his children already

lay, but in the churchyard of St John the Baptist, Hoxton, where he had been married

14 years earlier. He left his wife, Esther, a young widow with five children under

he age of 10. But her part in the Bostock story is not yet done - click on the link

below for details.

A year and a half later on 11 December 1853, George died at 5 Hackney Road; he was

just 35 years old. The doctor recorded the cause of death as ‘syrosis — two weeks’

(sic). The two most common causes of cirrhosis are alcohol and hepatitis. Given the

difficulties between George’s parents and the evidence of his father’s Will, the

natural conclusion is that George drunk himself into an early grave. Unusually, he

was not buried in the churchyard of St Leonard’s, where two of his children already

lay, but in the churchyard of St John the Baptist, Hoxton, where he had been married

14 years earlier. He left his wife, Esther, a young widow with five children under

he age of 10. But her part in the Bostock story is not yet done - click on the link

below for details.

George was born on 21 November 1818 in Holywell Lane, Shoreditch, the second child

of James Bostock and Marie Antoinette Wicks (Wix). A few weeks later, like so many

of the Bostock infants, he was baptised at the Church of St Leonard, although his

surname was entered into the baptism register incorrectly as ‘Boaster’. The church

is shown in the illustration on the right at about the same time of George’s baptism.

George was born on 21 November 1818 in Holywell Lane, Shoreditch, the second child

of James Bostock and Marie Antoinette Wicks (Wix). A few weeks later, like so many

of the Bostock infants, he was baptised at the Church of St Leonard, although his

surname was entered into the baptism register incorrectly as ‘Boaster’. The church

is shown in the illustration on the right at about the same time of George’s baptism.

It was here that George and Esther’s first child, George Rowland, was born on

29 November 1840. A month later, on Christmas day, George and Esther walked the short

distance to Church of St Leonard to baptise him. The Church, which stands at the

junction of the Hackney and Kingsland Roads, was a visible and integral part of their

lives; its chimes meant that they needed no clock.

It was here that George and Esther’s first child, George Rowland, was born on

29 November 1840. A month later, on Christmas day, George and Esther walked the short

distance to Church of St Leonard to baptise him. The Church, which stands at the

junction of the Hackney and Kingsland Roads, was a visible and integral part of their

lives; its chimes meant that they needed no clock.  Later that year, Esther became pregnant, giving birth to a daughter in May 1842.

She was named Marie Antoinette after George’s mother, and was baptised on Sunday,

21 May 1843 at the Church of St Leonard. Probably unbeknownst to George, in 1844

his father, James, made his Will. The Will was at great pains to divide everything

equally between James’ wife, legitimate children, common-

Later that year, Esther became pregnant, giving birth to a daughter in May 1842.

She was named Marie Antoinette after George’s mother, and was baptised on Sunday,

21 May 1843 at the Church of St Leonard. Probably unbeknownst to George, in 1844

his father, James, made his Will. The Will was at great pains to divide everything

equally between James’ wife, legitimate children, common- A year and a half later on 11 December 1853, George died at 5 Hackney Road; he was

just 35 years old. The doctor recorded the cause of death as ‘syrosis — two weeks’

(sic). The two most common causes of cirrhosis are alcohol and hepatitis. Given the

difficulties between George’s parents and the evidence of his father’s Will, the

natural conclusion is that George drunk himself into an early grave. Unusually, he

was not buried in the churchyard of St Leonard’s, where two of his children already

lay, but in the churchyard of St John the Baptist, Hoxton, where he had been married

14 years earlier. He left his wife, Esther, a young widow with five children under

he age of 10. But her part in the Bostock story is not yet done -

A year and a half later on 11 December 1853, George died at 5 Hackney Road; he was

just 35 years old. The doctor recorded the cause of death as ‘syrosis — two weeks’

(sic). The two most common causes of cirrhosis are alcohol and hepatitis. Given the

difficulties between George’s parents and the evidence of his father’s Will, the

natural conclusion is that George drunk himself into an early grave. Unusually, he

was not buried in the churchyard of St Leonard’s, where two of his children already

lay, but in the churchyard of St John the Baptist, Hoxton, where he had been married

14 years earlier. He left his wife, Esther, a young widow with five children under

he age of 10. But her part in the Bostock story is not yet done -