albert james monger (1904-

Early years

Early years

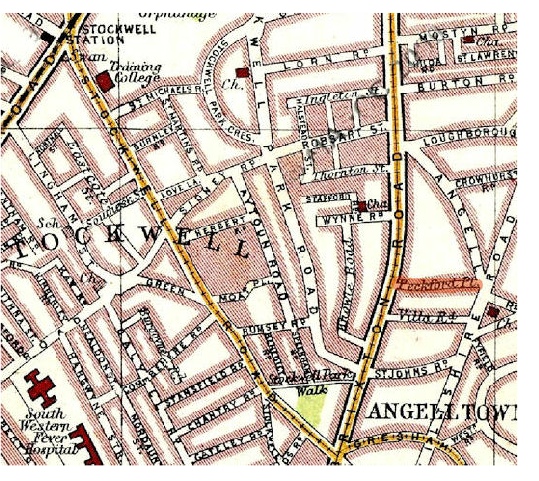

The fifth of twelve children born to George and Florence Beatrice Monger, Albert James was born on Monday 11 July 1904 whilst his family was living at 15 Peckford Place, just off the Brixton Road. Like many working class families of his generation, the Mongers moved regularly, although generally only a short distance. Home life was noisy and crowded but full of good humour, and days were spent at school, helping around the house and playing in the streets.

1920 was a momentous year in Albert’s life; it was the year he left school and went

out to full-

Albert and Ada, as she was always known, married on 20 March 1926 at Wandsworth Registrar’s

Office. Ada was only just 20 years old, b ut gave her age as 21 on the marriage certificate:

she was five months pregnant and wanted to make sure there were no objections to

the marriage. Among the guests were Ada’s elder sister, Kit and her husband, and

Albert’s sister, Edith Wyatt, and her husband. Albert and Ada gave their address

as 75 Livingstone Road, and they probably remained here until their first child,

Albert, was born five months later in August 1926.

ut gave her age as 21 on the marriage certificate:

she was five months pregnant and wanted to make sure there were no objections to

the marriage. Among the guests were Ada’s elder sister, Kit and her husband, and

Albert’s sister, Edith Wyatt, and her husband. Albert and Ada gave their address

as 75 Livingstone Road, and they probably remained here until their first child,

Albert, was born five months later in August 1926.

Married life

Albert and Ada settled down to married life and raising their growing family: Ruth (1927), Lillian Jeanee (October 1928), John ’Jack’ (1930), Edith Margaret ’Peg’ (1931) and Ivy Christine (1936). Money was tight and work not always easy to come by. Albert would cycle for miles to find work. On a Friday evening when work had finished for the week and he cycled home, Ada would ask the children “has he got his sack?”; if Albert had his tools in his sack, it was a bad sign and meant that the job had come to an end. But Albert could be relied upon to raise his family’s spirits and make them laugh, and there was nearly always a ha’penny pocket money for the children: unlike many fathers of his generation, Albert was a kind and loving father.

Through the years of the Depression, money was short. The family lived from week to week and it was common for items to be pawned to make ends meet throughout the week; Albert’s Sunday best would go in on Monday but would always be ready for him for the weekend when there were walks on the common, a few pints down the local pub, or Sunday tea at his sister Edith’s house, which last two hours and included cockles and shrimps, bread and butter, and cream cakes. In the summer, the family might go down to the hop farms in Kent, and Albert would join them for a week. At other times of the year, especially Christmas, there were gatherings when the family and friends would crowd around the piano for a song, usually culminating in old favourites such as ‘Knees up Mother Brown’ and the ‘Okey Cokey‘. Even if no one could read music someone could always manage a tune they had learnt to play by ear.

Britain at war

Life went on in this way until 1939. But at 11.15am on 3 September, the Prime Minister,

Neville Chamberlain who, only a year earlier, had declared that he had secured “peace

for our time” announced that Britain was at war with Germany. Initially, Albert was

too old to be called up and, as well as his age, he had a damaged firing finger —

perhaps the result of an accident at work — which would have given him exemptions

for certain types of duty. However, like most able bodied men in Britain, he volunteered

for home duty. Because of his building experience, he was in the Heavy Rescue Squad.

This squad was responsible for rescuing people from buildings and making safe buildings

which had been destroyed by bombing. With 71 major bombing raids during the months

from September 1940 to March 1941, during which time over 18,000 tons of high explosive

bombs were dropped on London, it was dangerous and demanding work. Albert’s son,

Bert, whilst home on leave commented that he was safer fighting overseas than he

was in London.

Life went on in this way until 1939. But at 11.15am on 3 September, the Prime Minister,

Neville Chamberlain who, only a year earlier, had declared that he had secured “peace

for our time” announced that Britain was at war with Germany. Initially, Albert was

too old to be called up and, as well as his age, he had a damaged firing finger —

perhaps the result of an accident at work — which would have given him exemptions

for certain types of duty. However, like most able bodied men in Britain, he volunteered

for home duty. Because of his building experience, he was in the Heavy Rescue Squad.

This squad was responsible for rescuing people from buildings and making safe buildings

which had been destroyed by bombing. With 71 major bombing raids during the months

from September 1940 to March 1941, during which time over 18,000 tons of high explosive

bombs were dropped on London, it was dangerous and demanding work. Albert’s son,

Bert, whilst home on leave commented that he was safer fighting overseas than he

was in London.

As a member of the Heavy Rescue Squad, Albert was issued with his kit and given first

aid training. On the days when he was on duty, he would come home at the usual time

from a days' work, have his tea and a brief rest before changing into his overalls

and cycling to the Air Raid Patrol (ARP) depot. If an air raid was sounded, the Squad

would wait until the all clear was given and then set to work. Their job was to make

sure houses and buildings were as safe as possible before the search for survivors

began. Sometimes the rescuers were too late and it became a matter of digging out

bodies. It was not unusual after a busy night at the height of the blitz in 1940-

blitz in 1940-

The end in sight

By 1944 the allies sensed that it was the ‘beginning of the end’ and a large-

The invasion began on 6 June 1944, a few weeks before Albert’s 40th birthday. Albert’s son, Bert, recalled that Albert was in one of the battalions that was responsible for taking Sword beach; certainly two battalions of the Green Howards were amongst the first to land in the assault. Albert was in a landing craft ferrying from a merchant ship which lay offshore, bringing vehicles and equipment to Sword beach. Although not part of the force securing and advancing from the beaches, the vessels at sea were under constant bombardment. Albert’s craft suffered a direct hit and it was only because he was situated at the rear of the vessel with the officers that he survived; many of the enlisted men on board were killed.

A return to normality

To the jubilation of the country, the war ended on 2 September 1945. Miraculously, Albert’s immediate family had survived unscathed but it had been a difficult time for everyone. Albert must have spent many hours worrying about his family, not only about their physical safety through the Blitz but how they were managing on his army pay of £2 5s 6d, although he must have taken comfort from the fact that Ada was a strong, capable woman.

After the war, life begun to resume something of a normality. However, Albert, like his neighbours, was surrounded by constant reminders of the war: burnt out shells of buildings, bomb craters, unexploded bombs, and rationing. As a result, housing was in short supply, so it may have come as welcome news when, in early 1952, Albert was given the opportunity to move his family to Merstham in Surrey. His eldest son, Bert, had already moved there in December 1951 with his family. Albert had visited one Sunday and his verdict was that Bert would miss London, find the country too quiet and be back within six months. Nevertheless, two months later on a snowy day in February 1952, Albert and Ada and their three youngest children (Jim, Chris and Brenda) packed up what few belongings they had and headed to Merstham.

Surrey life

Merstham is a village about 20 miles south of London. It dates to the seventh century

and is mentioned in the Domesday Book. Its chief industry, apart from farming, was

quarrying, and its quarries yielded both lime and a very fine limestone which was

used in the building of the King’s palace in 1259 and later for parts of Windsor

Castle, old St Paul’s Cathedral, and London Bridge.

Merstham is a village about 20 miles south of London. It dates to the seventh century

and is mentioned in the Domesday Book. Its chief industry, apart from farming, was

quarrying, and its quarries yielded both lime and a very fine limestone which was

used in the building of the King’s palace in 1259 and later for parts of Windsor

Castle, old St Paul’s Cathedral, and London Bridge.

In 1872 the village had 173 houses and a population of 846. Until the early 1950s,

when Albert and his family moved to Merstham, Merstham was made up of two parts:

old or ‘top’ Merstham which consisted of a few rows of picturesque cottages, a high

street, an ancient church, a railway station, a public houses or two, and The Feathers

Hotel; South Merstham consisted largely of residential houses dating from the late

nineteenth and early twentieth century. Beyond the village stretched open countryside,

some of which was marshy. After the war, the London County Council bought up large

parts of this land and building started i n earnest giving Merstham a third identity:

the Estate.

n earnest giving Merstham a third identity:

the Estate.

Merstham Estate consisted mainly of three-

Albert’s daughter Lilian and her family moved to Merstham in 1955 and Albert was once again surrounded by family, including an increasing number of grandchildren. But by 1961, all of the children, except Brenda, had left home and Albert, Ada and Brenda were living in a flat at 82 Portland Drive. Albert continued to work as a builders’ labourer, often travelling to London each day; he also worked on the building of Heathrow Airport.

The final chapter

By the early 1950s, Ada had been suffering from diabetes and poor health for some time. In December 1963 Albert’s world came crashing down when Ada had a heart attack and died: he never fully recovered from her loss. During the 37 years of their marriage she had been the driving force behind the family, she had kept them together during the lean years of the Depression, through the terrifying months of the Blitz, and had been the person that everyone turned to. On 23 March 1964, three days after his 38th wedding anniversary and just 16 weeks after Ada’s death, Albert had a heart attack. Although Dr Redd recorded the cause of death in medical terminology as a ‘cardiac infarction’, in layman’s terms, Albert died of a broken heart.

who’s related to whom

albert james monger

(1904-

lilian jeanee monger

(1928-

mary ann benham

living fenley

(born 1946)

living moss

(born 1968)

m

Albert James’ mother: Florence Beatrice Cawte

| paternal tree |

| maternal tree |

| index of names |

| monger photos |

| moss photos |

| collins photos |

| bostock photos |

| george moss |

| william moss |

| george c moss |

| eleanor evans |

| gregory family |

| thomas gregory |

| thomas gregory |

| sissey family |

| christopher sissey |

| sissey children |

| brisco family |

| william briscoe |

| john biscoe |

| susan webb |

| briscoe children |

| betsy biscoe |

| james bostock |

| george bostock |

| james g bostock |

| edwin f bostock |

| may bostock |

| marie wicks & sarah homan |

| homan bostock family |

| steward family |

| charles steward |

| ducro family |

| esther steward |

| mary & ann steward |

| stephen ducro |

| mary ducro |

| Ann_Briggs |

| hockerday family |

| thomas hockaday |

| mary ann hockerday |

| peters family |

| william peters |

| joseph peters |

| emily a peters |

| joseph collins |

| samuel collins |

| joseph collins |

| henry j collins |

| florence a collins |

| william shepherd |

| ann e shepherd |

| rogers family |

| john rogers |

| sarah a rogers |

| harvey family |

| thomas harvey |

| ann harvey |

| grigg family |

| william monger |

| charles monger |

| george monger |

| albert j monger |

| benham family |

| thomas benham |

| mary a benham |

| stephen dunford |

| fanny dunford |

| cawte family |

| robert cawte |

| william cawte |

| john r cawte |

| reynolds family |

| william reynolds |

| emma reynolds |