christopher sissey (1783-

Early years

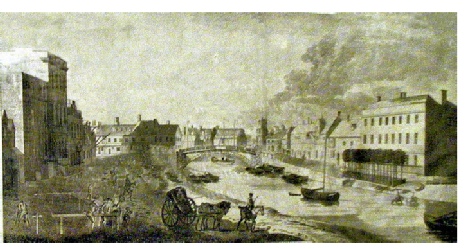

A Christopher Sissey was baptised on 5 December 1783 at the Church of St Peter in

Wisbech (pictured right) the son of Samuel and Elizabeth Sissey. Wisbech is a market

town in the Fens on the borders of Cambridgeshire and Norfolk, and is often called

‘The Capital of the Fens’. It is a busy port due to the navigable River Nene which

runs through the heart of the town. After the Fens were drained in the mid-

A Christopher Sissey was baptised on 5 December 1783 at the Church of St Peter in

Wisbech (pictured right) the son of Samuel and Elizabeth Sissey. Wisbech is a market

town in the Fens on the borders of Cambridgeshire and Norfolk, and is often called

‘The Capital of the Fens’. It is a busy port due to the navigable River Nene which

runs through the heart of the town. After the Fens were drained in the mid-

A strong, healthy lad, Christopher was apprenticed to a blacksmith, perhaps his father,

when he was about 11 or 12 years old, and by the time he was in his late teens, he

had learnt his craft. In rural communities, blacksmiths were the most important  craftsmen,

not only making horse shoes, but also making and repairing farm and household tools.

In the busy port of Wisbech, Christopher turned his hand to all kinds of smithing

and, as a skilled artisan, occupied a higher social and economic position than an

ordinary labourer. But for whatever reason, by 1815 Christopher had headed south.

Given the prosperity and growth of Wisbech, it seems unlikely he would have done

so to find employment; he may have had ambitions of a better life or perhaps the

boats that plied the River Nene made him yearn for new horizons, or maybe his reasons

for leaving the town were more pressing.

craftsmen,

not only making horse shoes, but also making and repairing farm and household tools.

In the busy port of Wisbech, Christopher turned his hand to all kinds of smithing

and, as a skilled artisan, occupied a higher social and economic position than an

ordinary labourer. But for whatever reason, by 1815 Christopher had headed south.

Given the prosperity and growth of Wisbech, it seems unlikely he would have done

so to find employment; he may have had ambitions of a better life or perhaps the

boats that plied the River Nene made him yearn for new horizons, or maybe his reasons

for leaving the town were more pressing.

Mail coaches made the journey to London every day with an outside seat costing 12s 6d; the price of the weekly stage coach was a hefty 18s and 6d, which represented about a week’s wages. But it is just as likely that he worked his way south, picking up odd jobs and labouring work along the way and hitching a ride with the wagon carts that were heading south.

Sarah Warren

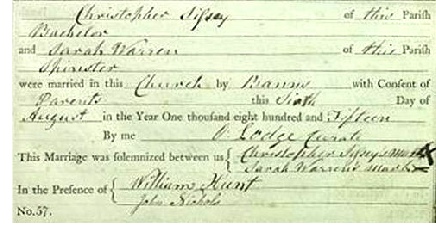

Less than two months after news reached reached Britain of Napoleon’s defeat at the

Battle of Waterloo, Christopher was living in Barking in Essex. It was probably here

that he met Sarah Warren. Perhaps as young as 15, she was considerably younger than

Christopher when they married on 6 August 1815 at the Church of St Margaret, ‘with

consent’ in view of the bride’s age. It was not uncommon for men to marry women much

younger than themselves but it was unusual that Christopher had not married earlier,

so perhaps Sarah was his second wife. Bride and groom both made their ‘mark’ in the

register (pictured right).

Less than two months after news reached reached Britain of Napoleon’s defeat at the

Battle of Waterloo, Christopher was living in Barking in Essex. It was probably here

that he met Sarah Warren. Perhaps as young as 15, she was considerably younger than

Christopher when they married on 6 August 1815 at the Church of St Margaret, ‘with

consent’ in view of the bride’s age. It was not uncommon for men to marry women much

younger than themselves but it was unusual that Christopher had not married earlier,

so perhaps Sarah was his second wife. Bride and groom both made their ‘mark’ in the

register (pictured right).

Their first child, Maria, was born in about 1817 in Stratford in Essex. Eliza Ann

was born the following year. From Stratford, the family moved a few miles north to

Walthamstow, where their son, Christopher, was baptised on 22 April 1821. Another

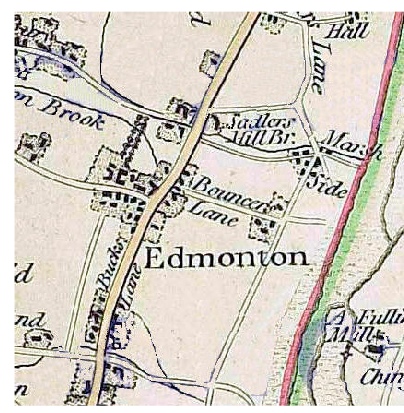

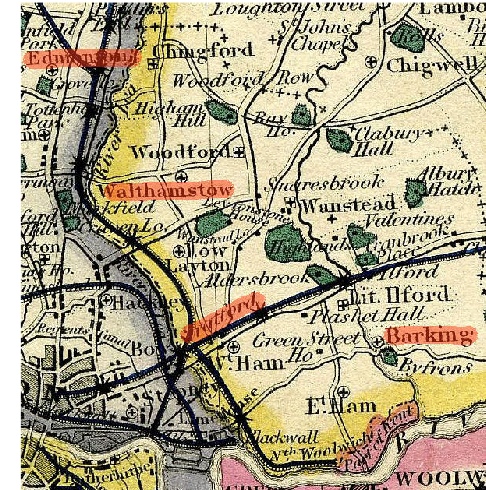

daughter, Caroline, was baptised in November 1823. The map at the bottom of the screen

shows the locations that the family moved between.

Their first child, Maria, was born in about 1817 in Stratford in Essex. Eliza Ann

was born the following year. From Stratford, the family moved a few miles north to

Walthamstow, where their son, Christopher, was baptised on 22 April 1821. Another

daughter, Caroline, was baptised in November 1823. The map at the bottom of the screen

shows the locations that the family moved between.

The family moved again between 1824 and 1827, this time to Edmonton. The view on the right shows Edmonton at about this time. It was a genteel town which had flourished in the eighteenth century, as fashionable residents increasingly settled there, many of them attracted by the regular coach services to London. However, by the nineteenth century, it had begun to lose its exclusiveness, and as prosperous traders moved in, the gentry moved out. According to the author, John T Smith, by 1800 it was inhabited by "retired embroidered weavers, their crummy wives and tightly laced daughters". Parts of the town also came to be covered with small, overcrowded tenements and lodging houses.

Edmonton’s  chief industries were market gardening and farming, on which almost half

of the population relied; another third of the population were employed in various

industries and manufacturing which included coach building, a glass mill, a soap

factory and a small silk mill. Nearly all of these industries owed their existence

to the London market and to Edmonton’s location on the River Lea, which helped in

the transporting of raw materials and finished goods.

chief industries were market gardening and farming, on which almost half

of the population relied; another third of the population were employed in various

industries and manufacturing which included coach building, a glass mill, a soap

factory and a small silk mill. Nearly all of these industries owed their existence

to the London market and to Edmonton’s location on the River Lea, which helped in

the transporting of raw materials and finished goods.

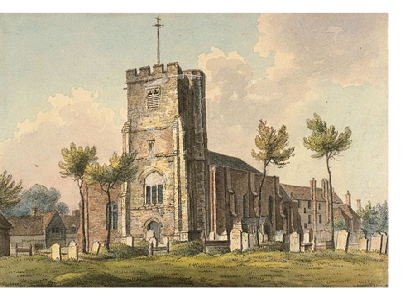

Christopher and his family settled in Church Street. The view on the left shows Church

Street in about 1900. As the name suggests, it was a short walk to the Church of

All Saints where another son was baptised in June 1827, although he had been born

eight months earlier on 8 October 1826. He was named Christopher, indicating that

Sarah and Christopher’s first son who was also named Christopher must have died.

The family continued to live in Church Street for a number of years, with Christopher

working as a blacksmith. In April 1829 Sarah gave birth to a boy, Henry, whom they

baptised a few weeks later; on 19 August, they returned to the Church to bury him.

gave birth to a boy, Henry, whom they

baptised a few weeks later; on 19 August, they returned to the Church to bury him.

Later that year, the family moved a short distance north to Sadler’s Mill Bridge.

This may have been to find work or a bid to reduce their living expenses. Life was

clearly very difficult for the Sissey family and in January 1830, Christopher and

Sarah returned to the Church of All Saints to bury their daughter, Eliza Ann. Shortly

after, Sarah found that she was pregnant. Mary Ann was born on 15 August 1830 and

was baptised on 5 September. Almost two years to the day on 9 September 1832, Sarah

and Christopher returned to the Church of All Saint to bury Caroline. Infant mortality

was a sad fact of life in the nineteenth century; 3 out of every 20 babies died before

their first birthday; amongst the working class the rate was 274 per 1,000 births,

rising to 509 per 1,000 births amongst the poor. By 1832, four of Christopher and

Maria’s seven children had died, indicating how difficult conditions were for the

Sisseys. For whatever reason, Christopher found it difficult to get employment and

Maria’s health suffered due to the family’s diet and living conditions.

The return to Barking

In search of work and perhaps hoping for support from Sarah’s family, Christopher and Sarah returned to Barking in about 1834. They settled in Ripple Side, a bleak spot bordering an area of dreary marshland. To make matters worse, Sarah gave birth to two more children over the next few years: William (baptised at the Church of St Margaret on 18 May 1834) and Eliza (baptised on 14 August 1839). Christopher’s occupation was given as ‘blacksmith’, but less than two years later, he was an inmate in Edmonton Workhouse.

The workhouse was on the south side of Church Street, west of the Church of All Saint’s,

and on the night of the 1841 census housed 109 inmates, although it could take almost

double that number. The Edmonton Poor Law Union had come into existence in February

1837. As part of its general review, the new Board of Guardians decided to replace

the Workhouse with purpose-

Unfortunately, no evidence has survives as to why Christopher entered the Workhouse, but as he was not too old to work, he must have been incapable of working either through illness or injury. Like so many people, he would never leave the workhouse. He remained an inmate for a further 19 years, dying in 1860. The burial entry gives his age as 70, but his death certificate records his age as 80. In reality, he was probably 77 years old. Considering the conditions in Victorian workhouses and the hard manual labour that many inmates carried out, he must have had a strong constitution, a result of his blacksmithing.

Widowhood

With her husband in the workhouse and her children to feed, Sarah and her three youngest

children were taken in by Sarah’s eldest daughter, Maria and her husband Thomas Gregory.

But the family struggled for survival and and not even their combined wages could

provide enough. Maria died on New Year’s Day 1847; she was about as old as the century

itself. The cause of death was given as ‘marasmus — 2 years’; marasmus is a medical

term for malnutrition and wasting of the body due to lack of intake of food and protein

— in effect, slow starvation.

With her husband in the workhouse and her children to feed, Sarah and her three youngest

children were taken in by Sarah’s eldest daughter, Maria and her husband Thomas Gregory.

But the family struggled for survival and and not even their combined wages could

provide enough. Maria died on New Year’s Day 1847; she was about as old as the century

itself. The cause of death was given as ‘marasmus — 2 years’; marasmus is a medical

term for malnutrition and wasting of the body due to lack of intake of food and protein

— in effect, slow starvation.

After her mother’s death, Maria and her husband were unable to care for Maria’s brothers and sisters. Read what became of Mary Ann, Eliza and William Sissey.

who’s related to whom

maria sissesy

(1817-

eliza gregory

(1844-

christopher sissey

(1783-

william moss

(1911-

sarah warren

m

samuel sissesy

living moss

(born 1947)

living moss

(born 1968)

william moss

m

| paternal tree |

| maternal tree |

| index of names |

| monger photos |

| moss photos |

| collins photos |

| bostock photos |

| george moss |

| william moss |

| george c moss |

| eleanor evans |

| gregory family |

| thomas gregory |

| thomas gregory |

| sissey family |

| christopher sissey |

| sissey children |

| brisco family |

| william briscoe |

| john biscoe |

| susan webb |

| briscoe children |

| betsy biscoe |

| james bostock |

| george bostock |

| james g bostock |

| edwin f bostock |

| may bostock |

| marie wicks & sarah homan |

| homan bostock family |

| steward family |

| charles steward |

| ducro family |

| esther steward |

| mary & ann steward |

| stephen ducro |

| mary ducro |

| Ann_Briggs |

| hockerday family |

| thomas hockaday |

| mary ann hockerday |

| peters family |

| william peters |

| joseph peters |

| emily a peters |

| joseph collins |

| samuel collins |

| joseph collins |

| henry j collins |

| florence a collins |

| william shepherd |

| ann e shepherd |

| rogers family |

| john rogers |

| sarah a rogers |

| harvey family |

| thomas harvey |

| ann harvey |

| grigg family |

| william monger |

| charles monger |

| george monger |

| albert j monger |

| benham family |

| thomas benham |

| mary a benham |

| stephen dunford |

| fanny dunford |

| cawte family |

| robert cawte |

| william cawte |

| john r cawte |

| reynolds family |

| william reynolds |

| emma reynolds |