george charles moss (1873-

Early years

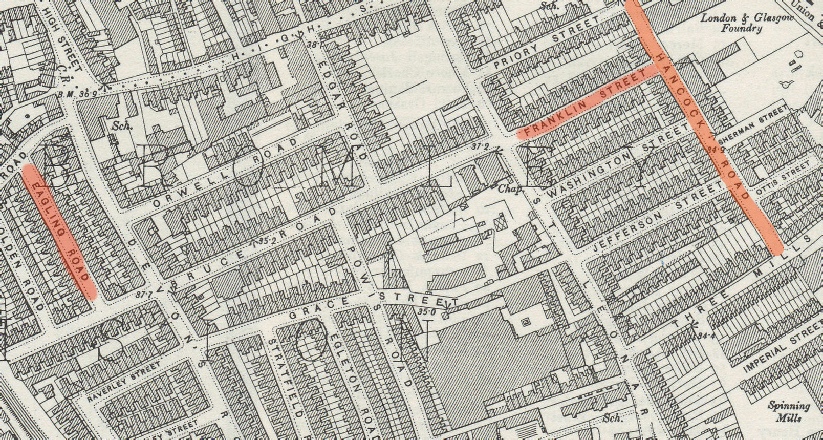

George Charles Moss was born on 20 February 1873 at 7 Ammiel Terrace, Bromley-

George Charles Moss was born on 20 February 1873 at 7 Ammiel Terrace, Bromley-

In his book, Men of the Tideway, Dick Fagan recalled:

“a handful of names seemed to account for an astonishing number of lightermen. Also many lightermen had married daughters or sisters of other lightermen, so you had a great number of uncles and nephews and cousins sculling around, as well as sons, fathers and grandfathers. Often the family resemblance between relatives was striking .... You'd keep thinking you were running into the identical man at different parts of the river twenty times on the same day”.

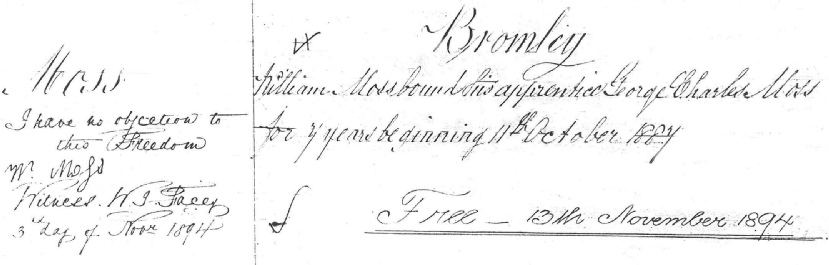

Freemen of the river

The Mosses were typical of the family that Dick Fagan describes; over the years,

George’s brothers William, Alfred, Arthur and Walter were bound as apprentices, and

all gained their freedom apart from Arthur. Only two years after he was bound, George

was a witness at the wedding of his sister, Ellen, to Frederick Richard Brown, a

barge lighterman just a few years older than George. No doubt, Frederick had been

introduced to Ellen by one of her brothers. The family ties were strengthened further

in 1897 when George’s widowed father, William, married Susan Dodson (née Brown),

who was almost certainly related to Frederick.

was a witness at the wedding of his sister, Ellen, to Frederick Richard Brown, a

barge lighterman just a few years older than George. No doubt, Frederick had been

introduced to Ellen by one of her brothers. The family ties were strengthened further

in 1897 when George’s widowed father, William, married Susan Dodson (née Brown),

who was almost certainly related to Frederick.

These connections show the deep-

Betsy Biscoe

Betsy Biscoe

It is uncertain when George first met Betsy. It may have been at Ellen and Frederick

Brown’s wedding in November 1889, although it could just have easily been at ‘The

Seven Stars’. The young couple were clearly taken with one another and during the

Summer of 1891 the 17-

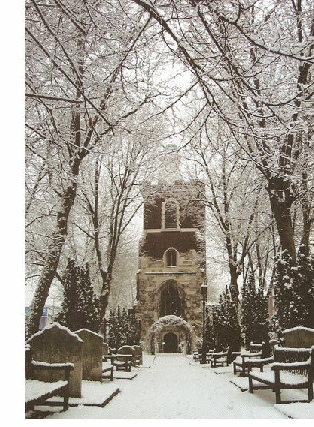

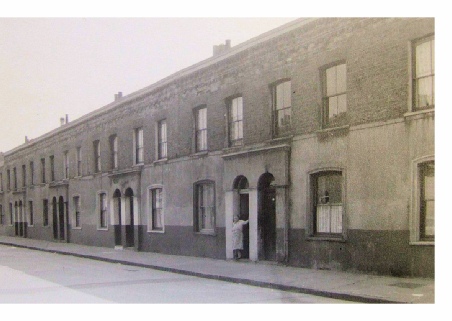

Still only 18 years old, George was classed as a minor and, as an apprentice lighterman, forbidden to marry under his articles of apprenticeship. Fortunately, for George, he was apprenticed to his father so it was easy to bend the rules. Even so, George and Betsy waited until Christmas day 1891, when a heavily pregnant Betsy made her way down the aisle of the Church of St Mary (shown on the right). If their families attended the wedding, they did not act as witnesses; perhaps they were at home enjoying their Christmas lunch, unlike the unfortunate vicars who had already married twelve couples that day. Six weeks later on 6 February 1892, whilst George and Betsy were living at 21 Eagling Road (pictured below in the 1930s), Betsy gave birth to a daughter who was named Susan Mary Ann after Betsy’s mother. She was baptised a few weeks later at the Church of St Mary.

By now, George had obtained his two- he gained his freedom on 3 November 1894, becoming a freeman of the River.

About the same time, Betsy gave birth to a second child, Elizabeth Eliza, this time

named after George’s mother. A third daughter, Maria Elizabeth, followed in March

1897. By 1898, George and his rapidly expanding family was living at 16 Hancock Road,

and it was here that George’s first son, Alfred, was born on 15 May 1898.

he gained his freedom on 3 November 1894, becoming a freeman of the River.

About the same time, Betsy gave birth to a second child, Elizabeth Eliza, this time

named after George’s mother. A third daughter, Maria Elizabeth, followed in March

1897. By 1898, George and his rapidly expanding family was living at 16 Hancock Road,

and it was here that George’s first son, Alfred, was born on 15 May 1898.

A growing family

During this time, George worked on the river and Betsy ran the house and raised the

children. As a lightermen, George worked long days and often nights, dictated by

the turn of the tide and the winds. At first, George and Betsy shared a house with

George’s brother and sister-

Early in 1902 Emma found herself pregnant again and David and Emma moved out of Marner

Street. George and Betsy were still living at Marner Street in April 1903 when their

son, Alfred, contracted measles. Measles is a disease of the respiratory system caused

by a virus and is accompanied by coughing, fever and a runny nose. It is highly contagious

and it is estimated that 90% of people living in the same space, and without immunity,

will catch it. Alfred was admitted to The Sick Asylum in Bromley-

In about 1904, George and his family moved to 24 Devas Street, a few streets south

of Ammiel Terrace. It must have been with relief and a sense of trepidation that

George Charles, named after his father, was born on 18 June 1904, followed by Albert

in 1907. Another daughter, Katie, was born in 1909. She was born with a cleft palate;

today the condition c an be treated successfully, but in 1909 it would have been a

cause of anxiety to George and Betsy. On the morning of 23 February 1910, Betsy found

Katie dead in her cot. An inquest was held on 25 February 1910 which concluded that

Katie had died of natural causes and had suffered a convulsion, caused by her difficulty

in breathing due to her cleft palate.

an be treated successfully, but in 1909 it would have been a

cause of anxiety to George and Betsy. On the morning of 23 February 1910, Betsy found

Katie dead in her cot. An inquest was held on 25 February 1910 which concluded that

Katie had died of natural causes and had suffered a convulsion, caused by her difficulty

in breathing due to her cleft palate.

By the time the night of the 1911 census, Betsy had borne eight children, only four of whom had survived. Coincidentally, George’s brother, David and his wife, Emma, had also lost four of their children: even for the time, the mortality rate was high. Just a month after the census, on 4 May 1911, Betsy gave birth to another son, William Ronald — their ninth child. Although still living in Devas Street, the family occupied only two rooms.

Towards the end of 1912, Betsy discovered she was pregnant. With her experience, one wonders how long it was until Betsy was able to break the news to George that she was carrying twins; Clara and Thomas Arthur were born in July 1913 brining the number of children she had borne to eleven, four of whom had died whilst children. By this time, the family was living in nearby Franklin Street. The photograph above shows 19 and 21 Franklin Street in about 1900, only a few doors down from the Moss household. A final child, John, was born in the Spring of 1917.

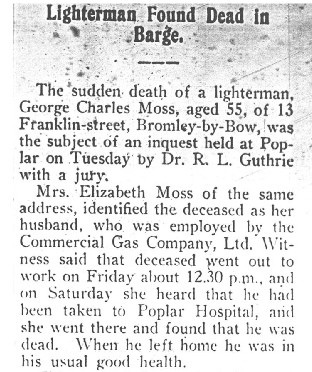

Another inquest

Despite the tragedies they had suffered, George and Betsy were better off than many

of their neighbours. As a lighterman, George’s prospects were good and he nearly

always had work, bringing home a good wage. In his later years, George worked as

a lighterman for the Commercial Gas Company which owned Poplar Gas Works. On 9 November

1928, George left home just after noon for St Bride’s Wharf in Wapping, where he

had arranged to meet Sidney Whitehorn, a friend of some 14 years, aboard the barge

Ammonia. They left for Bow Creek at 2.35pm and arrived there after two hours rowing.

Whilst waiting for the tide to subside they had a cup of tea and then rowed the barge

up the creek to near Leven Road which ran next to Poplar Gas Works where they moored

at around midnight. An hour later George put the barge into deep water. After resting

for a while, he got up to check the weather and to go to

Despite the tragedies they had suffered, George and Betsy were better off than many

of their neighbours. As a lighterman, George’s prospects were good and he nearly

always had work, bringing home a good wage. In his later years, George worked as

a lighterman for the Commercial Gas Company which owned Poplar Gas Works. On 9 November

1928, George left home just after noon for St Bride’s Wharf in Wapping, where he

had arranged to meet Sidney Whitehorn, a friend of some 14 years, aboard the barge

Ammonia. They left for Bow Creek at 2.35pm and arrived there after two hours rowing.

Whilst waiting for the tide to subside they had a cup of tea and then rowed the barge

up the creek to near Leven Road which ran next to Poplar Gas Works where they moored

at around midnight. An hour later George put the barge into deep water. After resting

for a while, he got up to check the weather and to go to the toilet. At about 1.40am

Sidney got up to check on him as he had been gone some time. He found him lying in

the cabin. A police officer was called and George was taken to Poplar Hospital where

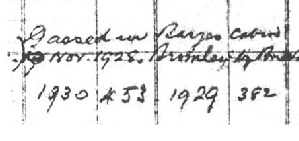

Betsy identified his body. The lightermans’s log book records that George was ‘gassed

in barge’s cabin’, although an inquest held on 13 November returned a verdict of

‘death due to natural causes’ brought about by a heart attack. The death certificate

also gives the cause of death as ‘coronary thrombosis’. George was buried on 19 November

at Tower Hamlets Cemetery; Betsy erected a headstone in his memory to which her details

were added a

the toilet. At about 1.40am

Sidney got up to check on him as he had been gone some time. He found him lying in

the cabin. A police officer was called and George was taken to Poplar Hospital where

Betsy identified his body. The lightermans’s log book records that George was ‘gassed

in barge’s cabin’, although an inquest held on 13 November returned a verdict of

‘death due to natural causes’ brought about by a heart attack. The death certificate

also gives the cause of death as ‘coronary thrombosis’. George was buried on 19 November

at Tower Hamlets Cemetery; Betsy erected a headstone in his memory to which her details

were added a fter her death in 1934:

fter her death in 1934:

“In Loving Memory of my dear husband George Charles Moss

Died Nov 10 1928 Aged 55 Years, ‘Gone but not Forgotten’

Also Betsy Elizabeth Moss wife of the above who passed away 23rd August 1934. ‘Gone but not forgotten’

Such a headstone would have been a luxury which few other working class families could have afforded. George may have saved during his life or it is possible that Betsy received a payout from the Commercial Gas Company. Although he did not leave a Will, the grant of probate shows that George’s estate was valued at £266 18s 6d — more than a year’s wages at a time when skilled labourers were earning about £4 a week, and an indication of how far George had come, at least financially if not in miles, from his own father who, only twelve years earlier had been buried with little fanfare and no lasting memorial to mark the spot.

With thanks to George Moss, the grandson of George Charles Moss and the last of the Moss lighterman, for sourcing the newspaper articles and locating George Charles Moss’s headstone.

william moss

george charles moss

(1873-

m

william moss

(1911-

living moss

(born 1947)

living moss

(born 1968)

who’s related to whom

George’s son: William Moss

click the tree for details

| paternal tree |

| maternal tree |

| index of names |

| moss tree |

| monger photos |

| moss photos |

| collins photos |

| bostock photos |

| george moss |

| william moss |

| george c moss |

| william evans |

| eleanor evans |

| gregory family |

| thomas gregory |

| thomas gregory |

| sissey family |

| christopher sissey |

| sissey children |

| brisco family |

| webb family |

| sykes family |

| william briscoe |

| john biscoe |

| briscoe children |

| betsy biscoe |

| charles webb |

| thomas webb |

| susan webb |

| nathaniel sykes |

| james bostock |

| george bostock |

| james g bostock |

| edwin f bostock |

| may bostock |

| marie wicks & sarah homan |

| homan bostock family |

| steward family |

| charles steward |

| ducro family |

| esther steward |

| mary & ann steward |

| stephen ducro |

| mary ducro |

| Ann_Briggs |

| hockerday family |

| thomas hockaday |

| mary ann hockerday |

| peters family |

| william peters |

| joseph peters |

| emily a peters |

| joseph collins |

| samuel collins |

| joseph collins |

| henry j collins |

| florence a collins |

| william shepherd |

| ann e shepherd |

| rogers family |

| john rogers |

| sarah a rogers |

| harvey family |

| thomas harvey |

| ann harvey |

| grigg family |

| william monger |

| charles monger |

| george monger |

| albert j monger |

| benham family |

| thomas benham |

| mary a benham |

| stephen dunford |

| fanny dunford |

| cawte family |

| robert cawte |

| william cawte |

| john r cawte |

| reynolds family |

| william reynolds |

| emma reynolds |