george monger (1877-

Early years

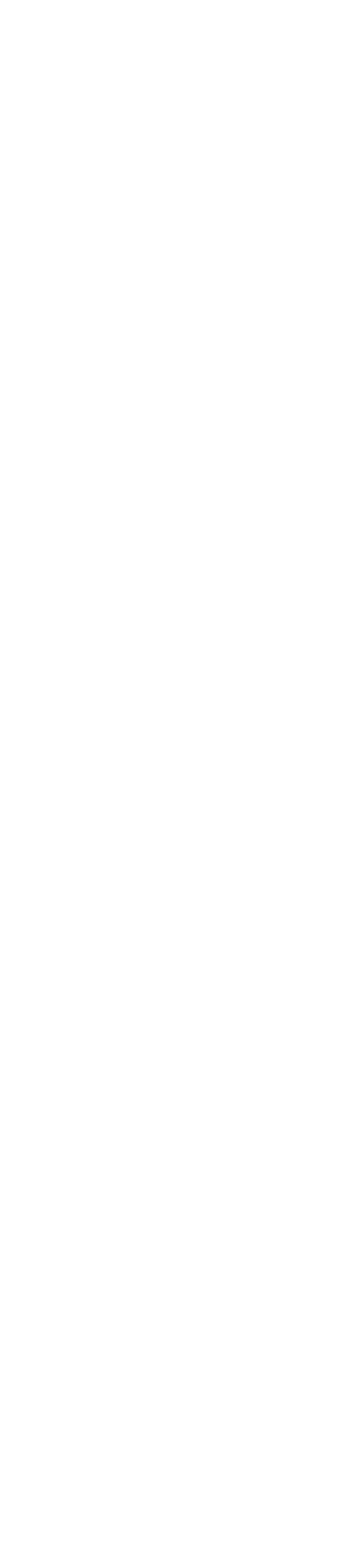

One of the youngest of the eleven children born to Charles and Mary Ann Monger, George

was born on 3 May 1877 at a cottage on the Old Road at Pot Bridge near Odiham. The

map of 1810 below shows that Pot Bridge was a hamlet containing a sufficient number

of dwellings to warrant  a place name; today it is marked only by a road name: Pot

Bridge Old Road which contains several houses and comes to a dead end at a busy ‘A’

road.

a place name; today it is marked only by a road name: Pot

Bridge Old Road which contains several houses and comes to a dead end at a busy ‘A’

road.

The Hampshire of the 1870s was a far cry from the place that George’s father had

been born into only forty years earlier; machinery had taken over many of the labour-

George’s childhood also differed from that of his father, since he was one of the

first generation of children to be required legally to attend school. The Education

Acts of 1876 and 1880 made full-

The changing face of the countryside

The advancements made in education were due largely to the philanthropic fervor of the new middle class, grown prosperous through the opportunities of science and technology. But this advancement also caused great hardship for rural Britain. In 1879, the wettest season in living memory produced low crop yields, but to compete with the produce of the American prairies, which could now ship large quantities of grain by steam ship to Britain, farmers were unable to increase prices of English wheat. The result was that agricultural wages were forced down; this was more pronounced in the south of England than in the north where farmers had to compete with the wages being paid by the industrial towns. Unsurprisingly, there was an exodus from the countryside and between 1871 and 1881 the urban population increased by 25%, leaving many rural villages with fewer inhabitants than in the Middle Ages.

One morning in the early 1890s, George packed up his worldly possessions, hopped

aboard a London-

The big smoke

As a young man arriving from a small rural hamlet into the heart of the British Empire,

London must have been overwhelming, noisy, dirty, and crowded. Did the unfamiliar

sights and sounds, different accents and faces, and new experiences around every

corner fill George with a sense of excitement and promise, or with trepidation and

dread? Who knows. What is clear is that George never returned to live in Hampshire.

He had made his bed and he would lie on it. And it wasn’t long before he was doing

more than that! The streets of London may have been crowded, but for a young man,

more people meant more girls.

As a young man arriving from a small rural hamlet into the heart of the British Empire,

London must have been overwhelming, noisy, dirty, and crowded. Did the unfamiliar

sights and sounds, different accents and faces, and new experiences around every

corner fill George with a sense of excitement and promise, or with trepidation and

dread? Who knows. What is clear is that George never returned to live in Hampshire.

He had made his bed and he would lie on it. And it wasn’t long before he was doing

more than that! The streets of London may have been crowded, but for a young man,

more people meant more girls.

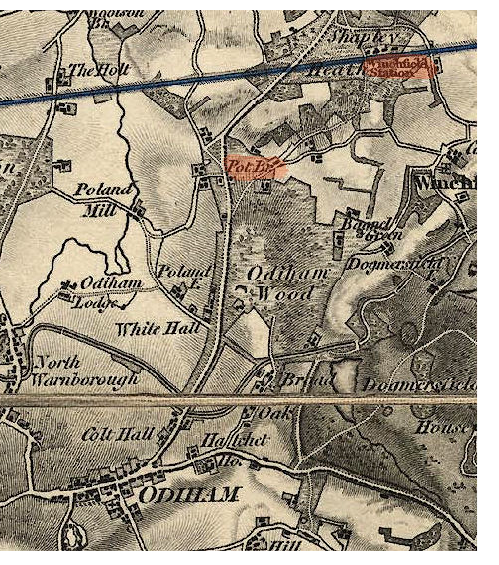

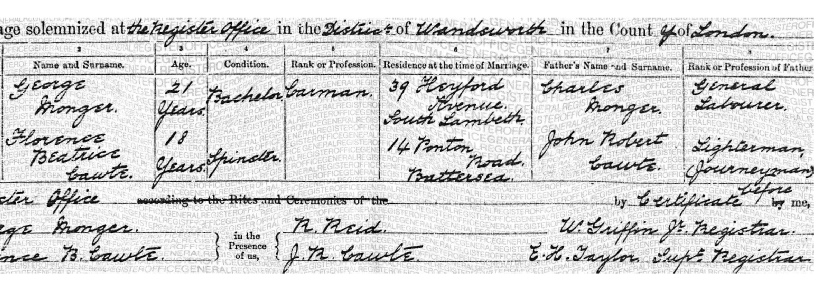

In 1898, George was lodging at 39 Heyford Avenue in South Lambeth (see picture on

the right and the map below). Florence Beatrice Cawte lived a few streets away in

Ponton Road by Nine Elms Station with her father and younger siblings. Their backgrounds

were very different: George was fresh from the country, whereas Florence was a city

girl whose family had lived south of the River Thames for over a hundred years. But

opposites often attract and on 2 June 1898 George married Florence at the Register

Office in Wandsworth, witnessed by R Reid and Florence’s father, John. Florence was

four months pregnant. For George, for whom life’s main events — hatching, matching

and dispatching — had taken place in ancient country parish churches, a civil wedding

ceremony must have been a potent symbol of his liberation from his old way of life

and the rigid hierarchy into which he had been born.

A growing family

After their marriage, George and Florence moved to 59 Ascalon Street (behind what is now Battersea Dogs Home) (see map above) where their daughter, Edith, was born less than five months later on 22 October 1898. George was working as a carman with one of the many omnibus companies, and money was tight. In 1899, there was another mouth to feed when Florence Rachel was born, and then Margaret in 1900.

Around 1901 George and his family relocated to Marsh Street in Leagrave in Bedfordshire.

By now, George was working as a carman for the railways and this was either a short-

Over the next seven years George and Florence’s family grew rapidly, with five more children arriving: Charles George (1903), Albert James (July 1904), Ethel Mary (towards the end of 1905), Rosaline Kate (1908), and John Lionel (summer 1909). During this time, the family moved between rented houses and in 1904 George and his were living at 15 Peckford Place, a few doors from the rooms that George had rented when he first arrived in London. By April 1911, George and Florence were living in three rooms at Granby Buildings with their six surviving children, two having died in infancy. George was working as a plate layer.

Life carried on much as it had always done, George working hard to make ends meet

and Florence raising their ever-

In early May 1920, Florence started feeling unwell. What began as a headache and

a sore neck, developed into a temperature, fever and sickness. George took her to

St Thomas’s Hospital where she was diagnosed with  cerebro-

cerebro-

During the years that followed Florence’s death, George had a number of jobs to to support his family including carman, platelayer, builder’s labourer, and a steam lorry driver. He continued to move homes regularly, although never more than a mile or two from the spot where he had first alighted from that Hampshire train in the 1890s. The photograph on the left may show George in the 1930s.

In the winter of 1939 he contracted a chest infection which turned to acute pneumonia and he was admitted to Lambeth Hospital. It was one of the three largest hospitals in London and until 1922 had been the Union workhouse. Its shadow still lingered not only the minds of the patients who were admitted but in the practices and attitudes of the staff who ran it and George died on 13 January 1939. He was 62 years old.

A reflection

In his lifetime, George witnessed more change than any generation that had preceded

him. On a personal level, he had moved from Hampshire to London, the first generation

of his family to do so. This had resulted in a fundamental shift in his life, transporting

him into the modern age and severing his links with the old agricultural way of life

as swiftly as the pistons of the locomotive that had carried him to London forty

years earlier. Did he reflect nostalgically on the life he had left behind and, as

in William Morris’s poem The Earthly Paradise, hanker after the ‘pack-

who’s related to whom

george monger

(1877-

lilian jeanee monger

(1928-

florence beatrice cawte

living fenley

(born 1946)

living moss

(born 1968)

m

George’s wife: Florence Beatrice Cawte

| paternal tree |

| maternal tree |

| index of names |

| monger photos |

| moss photos |

| collins photos |

| bostock photos |

| george moss |

| william moss |

| george c moss |

| eleanor evans |

| gregory family |

| thomas gregory |

| thomas gregory |

| sissey family |

| christopher sissey |

| sissey children |

| brisco family |

| william briscoe |

| john biscoe |

| susan webb |

| briscoe children |

| betsy biscoe |

| james bostock |

| george bostock |

| james g bostock |

| edwin f bostock |

| may bostock |

| marie wicks & sarah homan |

| homan bostock family |

| steward family |

| charles steward |

| ducro family |

| esther steward |

| mary & ann steward |

| stephen ducro |

| mary ducro |

| Ann_Briggs |

| hockerday family |

| thomas hockaday |

| mary ann hockerday |

| peters family |

| william peters |

| joseph peters |

| emily a peters |

| joseph collins |

| samuel collins |

| joseph collins |

| henry j collins |

| florence a collins |

| william shepherd |

| ann e shepherd |

| rogers family |

| john rogers |

| sarah a rogers |

| harvey family |

| thomas harvey |

| ann harvey |

| grigg family |

| william monger |

| charles monger |

| george monger |

| albert j monger |

| benham family |

| thomas benham |

| mary a benham |

| stephen dunford |

| fanny dunford |

| cawte family |

| robert cawte |

| william cawte |

| john r cawte |

| reynolds family |

| william reynolds |

| emma reynolds |