Early years

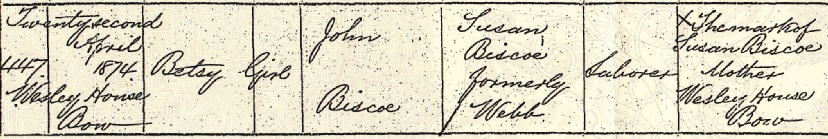

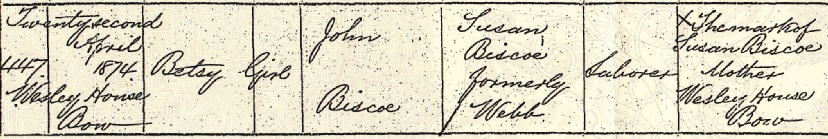

Betsy Biscoe — or Catley as she later called herself — was born on 22 April 1874,

the daughter of John Biscoe, a labourer from Bromley-by-Bow, and Susan Webb, who

had been born in Limehouse. Betsy herself was born in the interestingly-named ‘Wesley

House’ in Bow.

Betsy Biscoe — or Catley as she later called herself — was born on 22 April 1874,

the daughter of John Biscoe, a labourer from Bromley-by-Bow, and Susan Webb, who

had been born in Limehouse. Betsy herself was born in the interestingly-named ‘Wesley

House’ in Bow.

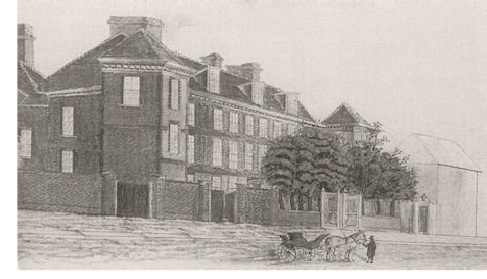

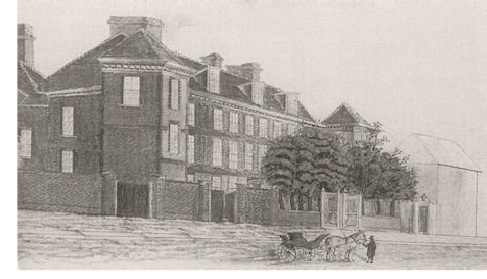

Wesley House dated back to Bow’s seventeenth century past. Tradition has it that

in 1606 a palace was built as a hunting lodge for James I facing the line of St Leonard's

Street. It was a grand residence of 24 rooms although there is no evidence to support

its royal connection, and the ‘Old Palace’, as it became to be known, was most likely

built as a second home for a courtier or wealthy London merchant. In 1750 it was

converted into two merchant houses and over the next hundred years went through a

variety of uses, including a boarding school. The engraving above shows the ‘Old

Palace’ in about 1850. Standing at right angles to the palace was a long row of wooden

houses, one with the words ‘Wesley House’ painted over the doorway; this is said

to have been one of the first meeting-houses in which John Wesley preached. Despite

its historical interest, by the time that Betsy was born there, it was probably very

run down.

It’s not known how long Betsy lived at Wesley House, but by 1881 she and her mother

and siblings were living at a house on the High Street; also living with them was

Charles Catley who Betsy viewed as her father; in later life, she referred to herself

as Betsy Catley, although on her wedding certificate she gave her name as Biscoe,

so she was aware that Charles was not her natural father.

Match making

As soon as she was old enough, Betsy went out to work, and in 1891 was working as

a match maker. There were a number of match firms in the area including Bryant &

May, which was only a short walk away and in 1875 employed 5,700 people, making it

the largest employer in the area. Its Quaker owners had begun with good intentions

when they opened the factory in 1861, but by 1888 conditions and pay in the factory

were poor. Work began at 6.30am in summer and 8am in winter, and ended at 6pm, with

work being carried out mainly by girls who had to stand the whole day. A girl could

typically earn between 4s and 9s a week, although excessive fines were imposed. What’s

more the white (or yellow) phosphorus caused severe health problems, most notoriously

‘phossy jaw’; toxic particles from white phosphorus entered the workers’ jawbones

through holes in the teeth, causing pain and facial swelling and the jaw to decay.

the largest employer in the area. Its Quaker owners had begun with good intentions

when they opened the factory in 1861, but by 1888 conditions and pay in the factory

were poor. Work began at 6.30am in summer and 8am in winter, and ended at 6pm, with

work being carried out mainly by girls who had to stand the whole day. A girl could

typically earn between 4s and 9s a week, although excessive fines were imposed. What’s

more the white (or yellow) phosphorus caused severe health problems, most notoriously

‘phossy jaw’; toxic particles from white phosphorus entered the workers’ jawbones

through holes in the teeth, causing pain and facial swelling and the jaw to decay.

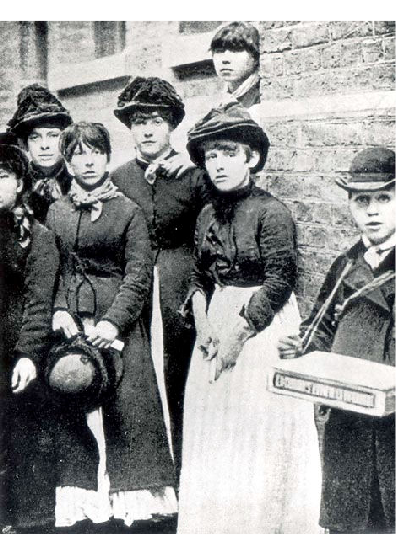

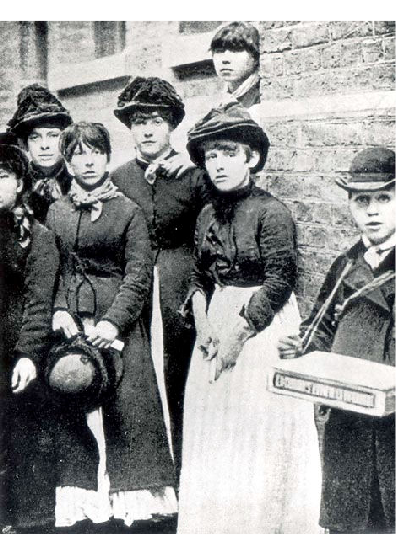

In July 1888, sparked by the dismissal of one of the workers, 1,400 match girls went

on strike (some of the strikers are shown in the photograph on the left). After three

weeks, they won improvements in working conditions and pay for the mostly female

workforce. Betsy may well have been among them although her name does not appear

in the strike register which lists about 300 strikers.

As if often the case, the difficult conditions bred a strong sense of camaraderie

and kinship, strengthened by the fact that many of the workers were related through

ties of marriage and friendship. The match girls worked hard and enjoyed what little

free time they had. A treat for a Saturday night was the music hall, where gallery

seats might cost as little as 3d. And if their favourite performer, Jenny Grainger,

was performing, the Bryant & May match girls would wait at the stage door to walk

her home down the Mile End Road.

No self-respecting woman would be seen outdoors without a hat and the match girls

formed ‘feather clubs’, each saving a small amount of money regularly. When they

had saved enough, they would buy the best and most flowery hat they could afford

and share it between them; just the thing for a night at the music hall, with priority

given to any girl who was courting.

A different sort of match making

In 1891 Betsy, was living in a house in Bromley-by-Bow High Street with her mother

and Charles Catley. Sharing the house were Ellen and Frederick Brown, and it may

have been through them that Betsy met the 18-year old George Charles Moss. Finding

a husband with prospects must have seemed like a far more sensible option to Betsy

than working 11 hours a day in a match factory faced with the dangers of phossy jaw,

so Betsy put on her finest hat and went courting. Not long after, the 17-year old

Betsy found herself pregnant, hardly surprising given that Betsy’s mother, Susan,

had borne her first child out of wedlock at about 17, and by 1891 had lived with

two men, neither of whom she had married; she was a poor role model. Betsy must have

been relieved when, on Christmas day 1891, she walked down the aisle of the Church

of St Mary in Stratford, only six weeks from her due date.

Over the next twenty or so years, Betsy gave birth to eleven children, four of whom

died in infancy; the first decade was particularly difficult with three of her five

children dying, including Alfred who died of measles in 1903. In 1909, Betsy gave

birth to a daughter whom she and George named Katie. She was born with a cleft palate.

Today the condition can be treated successfully, but in 1909 it was a cause of anxiety

to George and Betsy. On the morning of 23 February 1910, Betsy found Katie dead in

her cot. An inquest was held on 25 February 1910 which concluded that Katie had died

of natural causes and had suffered a convulsion, caused by her difficulty in breathing

due to her cleft palate.

whom she and George named Katie. She was born with a cleft palate.

Today the condition can be treated successfully, but in 1909 it was a cause of anxiety

to George and Betsy. On the morning of 23 February 1910, Betsy found Katie dead in

her cot. An inquest was held on 25 February 1910 which concluded that Katie had died

of natural causes and had suffered a convulsion, caused by her difficulty in breathing

due to her cleft palate.

Like most her contemporaries, Betsy’s married life was defined by the home: looking

after the children and running the house. With no modern conveniences, it was no

easy task. Food had to be bought almost every day; as well as the local market and

high street shops, Betsy picked up provisions at the store on the corner of Franklin

and Hancock Street (pictured below), or sent one of children.

Washing was a major undertaking performed as seldom as possible: great quantities

of water had to be boiled on a coal stove, clothes scrubbed and mangled, starched

and then ironed. In the early years of her marriage, Betsy and George shared a house

with Betsy’s brother- and sister-in-law, providing support and company.

Towards the end of 1912, Betsy discovered she was pregnant. One wonders how long

it was until Betsy was able to break the news to George that she was carrying twins;

Clara and Thomas Arthur were born in July 1913. By this time, the family were living

in Franklin Street. Another child, John, who would, to Betsy’s relief, be the youngest,

was born in the Spring of 1917, when Betsy was forty-three years old. After John’s

birth, life carried on much as it had always done until the Winter of 1928.

Another inquest

On 10 November 1928, there was a knock at the door. When Betsy saw the policeman

she must have feared the worst; accidents were not uncommon and drowning was an occupational

hazard for lighterman. Betsy was told that George had died in the cabin of his barge

and asked to go to Poplar Hospital to identify his body.

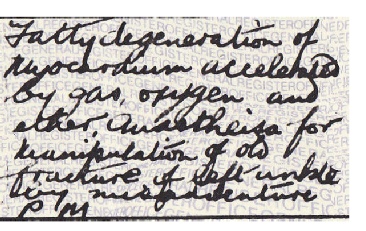

Following George’s death, Betsy found herself giving evidence at another inquest,

this time in front of a jury. The inquest returned a verdict of ‘death due to natural

causes’ although there had been talk that George had been gassed by coke fumes in

the cabin of his barge. Indeed, the lightermans’s log book records the cause of death

as ‘gassed in barge’s cabin’.

Betsy erected a headstone in George’s memory, a luxury which few other working class

families could have afforded. George may have saved during his life, or taken or

life insurance, or it is possible that Betsy received a payout from George’s employer,

the Commercial Gas Company. The grant of probate shows that George’s estate was valued

at £266 18s 6d — more than a year’s wages at a time when skilled labourers were earning

about £4 a week.

George’s legacy

George’s legacy

After George’s death, Betsy continued to live in Bow, moving to 73a Devons Road,

a busy street lined with shops (shown in the photograph on the road In about 1910).

Thanks to George’s legacy, she did not have to worry financially - one family rumour

suggested that she acted as a moneylender - but her health was not good. At some

point in her life, she had fractured her left ankle, probably the result of a fall,

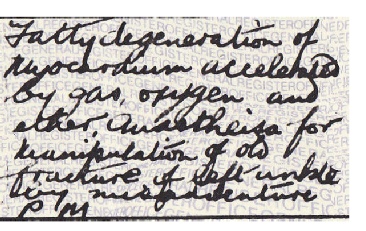

and it began to trouble her. On 23 August 1934 she underwent a procedure to correct

the problem and was given gas, oxygen and ether. This was a common form of anaesthesia

in the early twentieth century, although its safety had been called into question

at least a decade earlier. Betsy died during her operation.

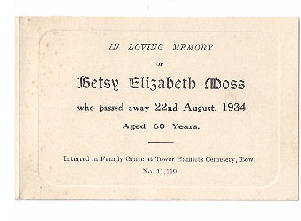

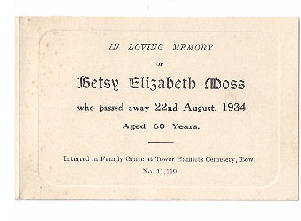

Like her husband’s death six years earlier, her death prompted an inquest, and probably

a line or two in the local papers. The Deputy Coroner’s verdict was that the cause

of her death had been ‘fatty degeneration of the heart’ which had been accelerated

by the anaesthetic. She was buried in the same grave as her husband in Tower Hamlets

Cemetery and her details added to the headstone. The memorial card below gives her

date of death as 22 August;  the death certificate records the date as 23 August.

the death certificate records the date as 23 August.

Betsy Biscoe — or Catley as she later called herself — was born on 22 April 1874,

the daughter of John Biscoe, a labourer from Bromley-

Betsy Biscoe — or Catley as she later called herself — was born on 22 April 1874,

the daughter of John Biscoe, a labourer from Bromley-

the largest employer in the area. Its Quaker owners had begun with good intentions

when they opened the factory in 1861, but by 1888 conditions and pay in the factory

were poor. Work began at 6.30am in summer and 8am in winter, and ended at 6pm, with

work being carried out mainly by girls who had to stand the whole day. A girl could

typically earn between 4s and 9s a week, although excessive fines were imposed. What’s

more the white (or yellow) phosphorus caused severe health problems, most notoriously

‘phossy jaw’; toxic particles from white phosphorus entered the workers’ jawbones

through holes in the teeth, causing pain and facial swelling and the jaw to decay.

the largest employer in the area. Its Quaker owners had begun with good intentions

when they opened the factory in 1861, but by 1888 conditions and pay in the factory

were poor. Work began at 6.30am in summer and 8am in winter, and ended at 6pm, with

work being carried out mainly by girls who had to stand the whole day. A girl could

typically earn between 4s and 9s a week, although excessive fines were imposed. What’s

more the white (or yellow) phosphorus caused severe health problems, most notoriously

‘phossy jaw’; toxic particles from white phosphorus entered the workers’ jawbones

through holes in the teeth, causing pain and facial swelling and the jaw to decay. whom she and George named Katie. She was born with a cleft palate.

Today the condition can be treated successfully, but in 1909 it was a cause of anxiety

to George and Betsy. On the morning of 23 February 1910, Betsy found Katie dead in

her cot. An inquest was held on 25 February 1910 which concluded that Katie had died

of natural causes and had suffered a convulsion, caused by her difficulty in breathing

due to her cleft palate.

whom she and George named Katie. She was born with a cleft palate.

Today the condition can be treated successfully, but in 1909 it was a cause of anxiety

to George and Betsy. On the morning of 23 February 1910, Betsy found Katie dead in

her cot. An inquest was held on 25 February 1910 which concluded that Katie had died

of natural causes and had suffered a convulsion, caused by her difficulty in breathing

due to her cleft palate.  George’s legacy

George’s legacy

the death certificate records the date as 23 August.

the death certificate records the date as 23 August.