Early years

On Sunday 31 October 1811, after the morning service had finished, Charles and Mary

Steward baptised their daughter, Sarah Ann at Christ Church in Spitalfields. It was

an event that would occur about every two years, and on Sunday, 25 July 1813, they

baptised another daughter, Mary Ann. Charles followed in 1815, Ann Martha in January

1817, Eliza in May 1819 and Esther in April 1821. In all, five daughters and a son.

As they grew up, the girls’ days were filled with learning those skills that they

would need, hopefully, as wives and mothers: running the house, cooking, washing

and needlework, as well as learning to read and write, no doubt a legancy of their

maternal Huguenot heritage.

Mary Ann. Charles followed in 1815, Ann Martha in January

1817, Eliza in May 1819 and Esther in April 1821. In all, five daughters and a son.

As they grew up, the girls’ days were filled with learning those skills that they

would need, hopefully, as wives and mothers: running the house, cooking, washing

and needlework, as well as learning to read and write, no doubt a legancy of their

maternal Huguenot heritage.

When their father died in 1824 at the age of about forty, the girls were equipped

with valuable skills. Eliza and Esther both found husbands. Sarah Ann gained employment

as a cook, a position which was a step up from the ordinary domestic servant and

which paid twice the wages of a house maid. Mary Ann and Ann Martha also put their

skills to use. In 1841, Mary was working as a dress maker and Ann Martha as a straw

bonnet maker. T he ladies collected the materials and orders from their employer and

carried out the work at home, returning the finished garments and bonnets to their

employer at the appointed time. During this time, Mary Ann and Ann Martha were living

at 2 Wilkes Street in Spitalfields with their mother, Mary, and grandmother, Ann

Ducrow. It was a respectable address and made possible because of Ann Ducrow’s independent

income. Perhaps they worked in the garret room where the elongated windows allowed

the light to flood in. If so, and if they had glanced up, they would have seen the

familiar spire of Christ Church towering over them, the chimes of its bells regulating

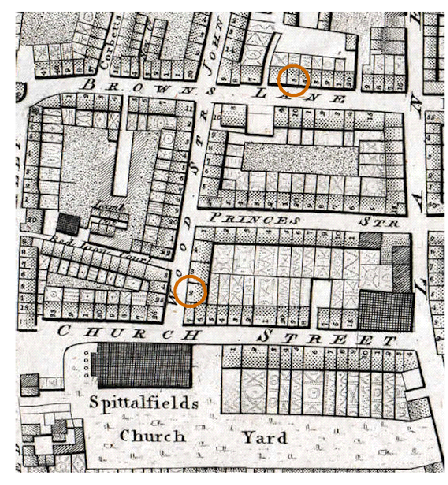

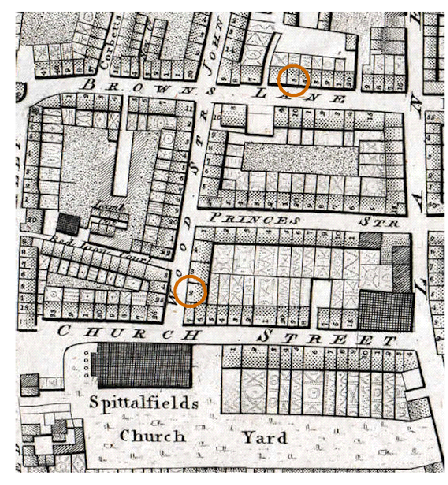

their waking hours. The photographs show (above) the front door of 2 Wilkes Street

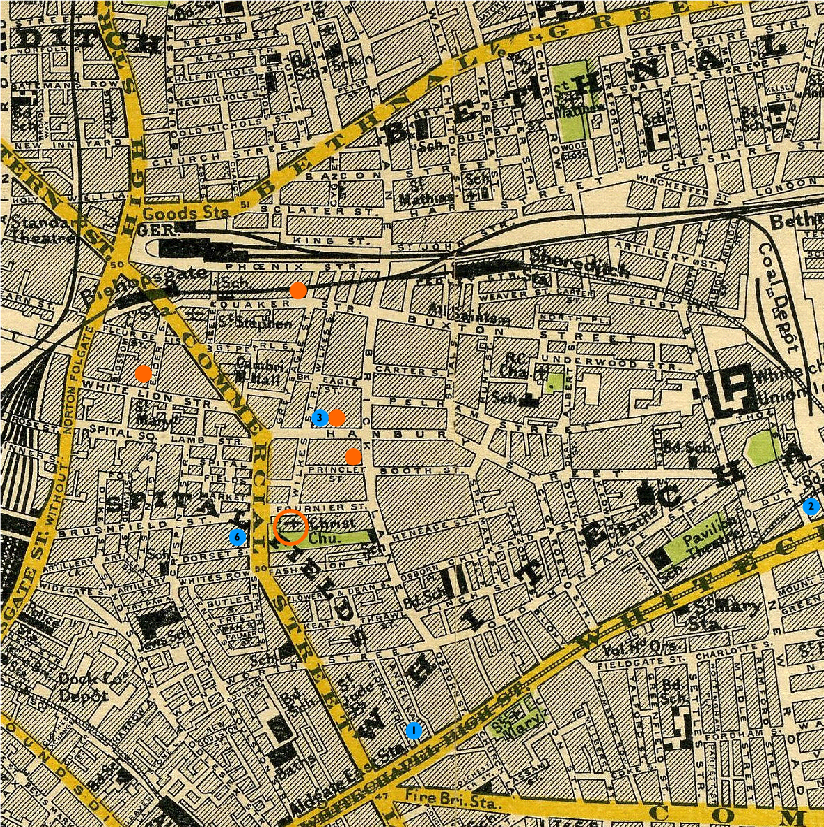

and (right) a view of Christ Church from the garret room. The map below shows Wilkes

Street (Wood Street) in about 1800.

he ladies collected the materials and orders from their employer and

carried out the work at home, returning the finished garments and bonnets to their

employer at the appointed time. During this time, Mary Ann and Ann Martha were living

at 2 Wilkes Street in Spitalfields with their mother, Mary, and grandmother, Ann

Ducrow. It was a respectable address and made possible because of Ann Ducrow’s independent

income. Perhaps they worked in the garret room where the elongated windows allowed

the light to flood in. If so, and if they had glanced up, they would have seen the

familiar spire of Christ Church towering over them, the chimes of its bells regulating

their waking hours. The photographs show (above) the front door of 2 Wilkes Street

and (right) a view of Christ Church from the garret room. The map below shows Wilkes

Street (Wood Street) in about 1800.

A change in circumstance

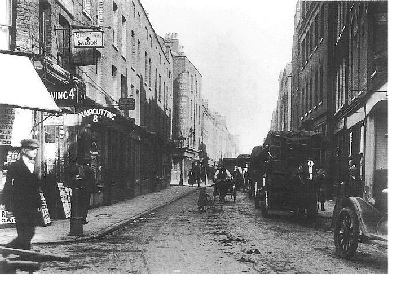

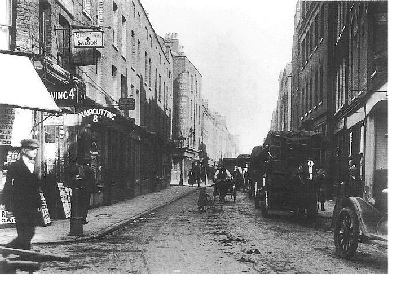

I n March 1845, Ann Ducro, then in her eighties, died. Presumably their grandmother’s

income ceased (although see below), and Mary Ann and Ann Martha left the faded gentility

of Wilkes Street and moved to a crowded house in Browns Lane (now Hanbury Street)

with their mother. Although it was only two streets away, it was a step down in the

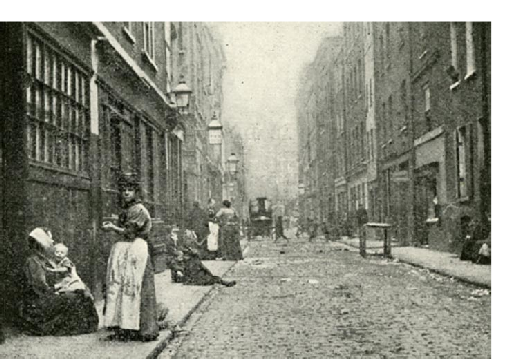

world. The photograph on the left shows Hanbury Street in 1918, and the map below

shows its location.

n March 1845, Ann Ducro, then in her eighties, died. Presumably their grandmother’s

income ceased (although see below), and Mary Ann and Ann Martha left the faded gentility

of Wilkes Street and moved to a crowded house in Browns Lane (now Hanbury Street)

with their mother. Although it was only two streets away, it was a step down in the

world. The photograph on the left shows Hanbury Street in 1918, and the map below

shows its location.

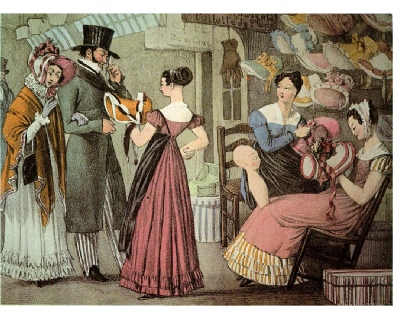

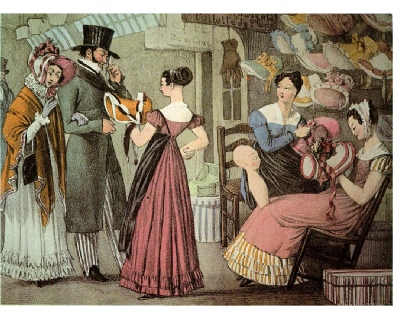

By the time of the next census in 1851, Mary had ceased dressmaking and was working

as a milliner. With the advent of mechanised sewing machines, perhaps she was able

to put her skills to better use by making hats, although the occupation was generally

poorly paid, and dictated by the London season. The illustration below shows a French

millinery shop in London; the gentleman appears more interested in examining the

pretty, rather brazen, milliner than the bonnet she is holding, much to the blushes

of his plain wife. Women in the millinery trade, whose whose skills were most in

d emand during the London society 'season', were often forced to supplement their

income in quieter months through prostitution, and London's fashionable Burlington

Arcade doubled as an upmarket red-light district in the late afternoons, although

there is nothing to suggest that the Ducro ladies had to resort to such measures.

emand during the London society 'season', were often forced to supplement their

income in quieter months through prostitution, and London's fashionable Burlington

Arcade doubled as an upmarket red-light district in the late afternoons, although

there is nothing to suggest that the Ducro ladies had to resort to such measures.

The decline of Spitalfields

By 1871, Mary Ann and Ann Martha were unable to take care of their infirm mother

and had little choice but to resign her to the workhouse. Mary Ann and Ann Martha

continued to living at 25 Browns Lane for another decade. But between 1871 and 1881,

after more than twenty years, they moved to 35 Booth Street (now Princelet Street

which lies to the east side of Brick Lane). It was a three-storey house with two

rooms front to back on each floor, and living in the house in 1881 were nine adults

and one child: the owner and his wife and son, a tailor and his wife, and three sisters

of French descent,  two of whom were fur sewers and the other a bonnet shape maker

(the photograph on the right shows Princelet Street today).

two of whom were fur sewers and the other a bonnet shape maker

(the photograph on the right shows Princelet Street today).

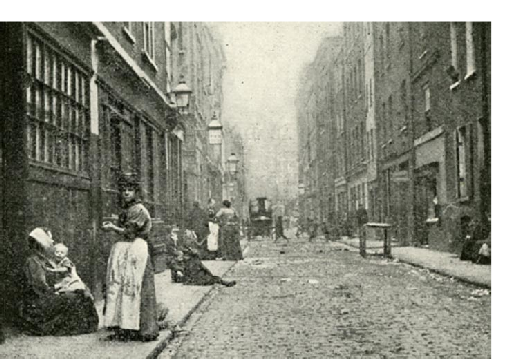

Since the 1680s, the character of Spitalfields has transformed constantly, its changes

mirroring the rise and fall of its economic fortunes. By the 1850s, although the

mass immigration of Jewish refugees from eastern Europe had not yet begun, there

was a small enclave of Dutch Jews in the area known as ‘Tenter ground’ and a synagogue

opened in 1869 at 19 Princelet Street (now Princes Street). Twenty years later, Spitalfields

and neighbouring Whitechapel had sunk to their lowest point. Desperately overcrowded,

they contained some of the most notorious slums in London: Flower and Dean Street

(one streets south of Fashion Street) was described as "perhaps the foulest and most

dangerous street in the whole metropolis" and Dorset Street (which ran west from

Red Lion Street) was called "the worst street in London", notorious for its doss

houses, each one of which might sleep up to 400 people a night for 4d or 6d. Robbery,

violence, homelessness, drunkenness and prostitution were endemic;  the Police Commission

estimated that there were 62 brothels in Whitechapel and 1,200 prostitutes (the estimated

number of prostitutes in London varies from a modest 7,000 to a staggering 80,000

depending on whether it was the Police Department or the Society for the Suppression

of Vice who was doing the estimating; scholars believe the Society's guess may be

closer to the truth, which would equate to more than one prostitute for every twelve

adult males in Greater London in the mid-nineteenth century).

the Police Commission

estimated that there were 62 brothels in Whitechapel and 1,200 prostitutes (the estimated

number of prostitutes in London varies from a modest 7,000 to a staggering 80,000

depending on whether it was the Police Department or the Society for the Suppression

of Vice who was doing the estimating; scholars believe the Society's guess may be

closer to the truth, which would equate to more than one prostitute for every twelve

adult males in Greater London in the mid-nineteenth century).

Hard times

One wonders how the two sisters reacted to their changing environment. On the face

of it, they were two aged spinsters sewing bonnets in a rented room. Did they fear

the outside world or had they adapted to it? Did they maintain their respectability

in the sea of vice that surrounded them, reflected in the grim faces that stare out

from the photograph of Dorset Street below? Given that they appear to have lived

in respectable households, supplementing their small income with their needle, without

the support of father, husband or brother, it would appear they managed. That they

remained in Spitalfields, despite its declining fortunes, was due to its familiarity

and the fact that their family had called it home for over 100 years.

Mary Ann and Ann Martha continued to work as milliners and by 1888 had moved to 34

Elder Street, a respectable street of Georgian houses that had once been rather grand.

It was where Ann Martha died on 18 February 1888 of bronchitis, her sisters Mary

Ann and Eliza (Fisher) by her side.

Ann Martha’s was most likely an unremarkable life and her passing went unnoticed

by all but a few. However, later that year, Spitalfields and Whitechapel were gripped

by a series of murders which drew the attention of the world on the streets that

had been familiar to Ann Martha during her life, and where Mary still lived.

In the grip of fear

On the morning of 8 August 1888 the body of a woman, later identified as Martha Tabram,

was discovered at George Yard Buildings in Whitechapel. Three weeks later, in the

early hours of the morning of 31 August, the mutilated body of Mary Ann ‘Polly’ Nichols

was found at Buck’s Row (Durward Street). Although drunken brawls and domestic violence

were a commonplace in Whitechapel, murder was a rare occurrence and it aroused a

certain amount of public interest, with people stopping in the street to discuss

the case. But it was the discovery of Annie Chapman’s mutilated body on the morning

of 9 September at 29 Hanbury Street that captured public attention. As news of the

murder spread, public anxiety turned into panic and a large crowd congregated in

front of the house in Hanbury Street. Curious onlookers arrived and householders

rented seats by windows overlooking the fatal spot. Costermongers did a brisk trade

selling provisions to the crowd, newspapers enjoyed massive sales and broadsheets,

some in verse and sung by hawkers to popular tunes, appeared in almost every street.

Living only 300 meters from the crime scene, Mary heard the news quickly as word

spread; it must have been a shock to her to learn that Mary Chapman’s body had been

discovered only two doors from where she had lived only ten years earlier, particularly

now she was living alone. The double murders of Elizabeth Stride and Catherine Eddowes

on the night of Sunday 30 September only fuelled rising fears stoked by press speculation

and sensationalism.

Five weeks later on 9 November, the world awoke to the news that another victim had

been found in nearby Dorset Street. Mary knew the street well and had walked down

it countless times in her youth, even if, in recent years, she avoided it due to

its very low character — it ran opposite Christ Church where Mary and her family

had been baptised, married and buried over the centuries. If Mary had not heard about

the murder soon after she had woken, it would have soon be brought to her attention.

It was the day of the Lord Mayor’s parade, but as news burst upon the crowd, thousands

deserted the parade route and converged on Dorset Street, and no doubt Elder Street

reverberated with the sound of footsteps and animated voices. With police cordoning

off the street, Bell Street and Commercial Street at either end became choked with

frightened but excited people.

After at least five brutal murders, the east end waited with baited breath. However,

whilst there were attempts to link other murders to the ‘Ripper’, Mary Kelly is generally

considered to be the last of his victims, and eventually Whitechapel breathed a sigh

of relief, although it is doubtful that any woman who lived through that Summer of

fear felt truly safe walking the streets after dark — not that any respectable woman

would be seen on the streets alone after dark, certainly not Mary who was by now

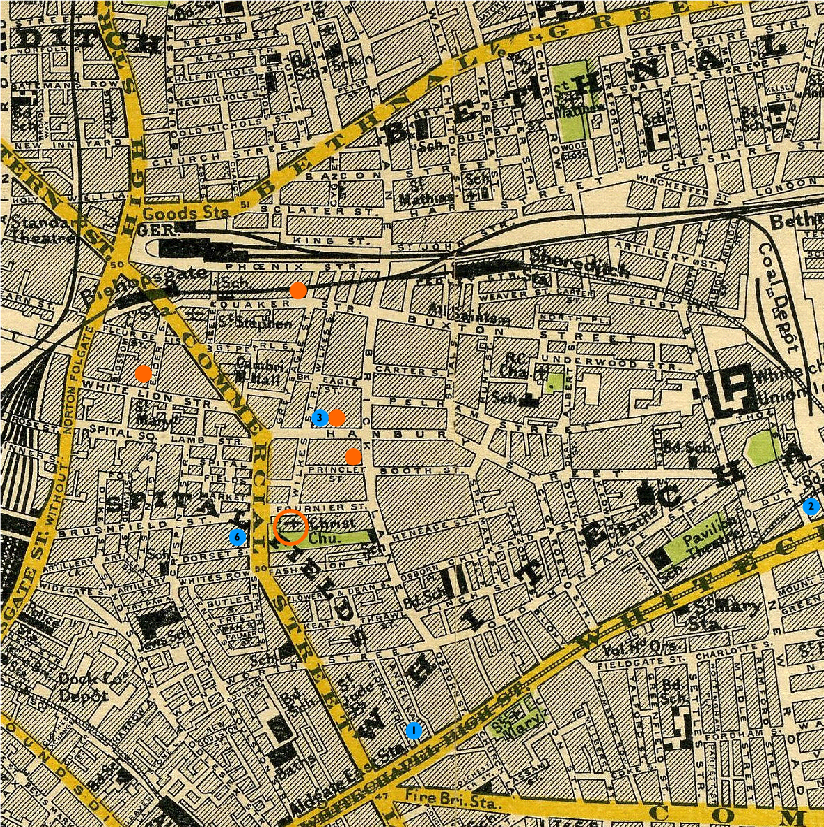

75 years old. The map below shows in blue the locations where the Ripper’s victims

were found; the places where Mary Ann and Ann Martha lived are show in orange.

The final years

Mary continued to live at 34 Elder Street (pictured below) for another five years,

and in the 1891 census was shown as occupying two rooms and living on private means.

The most likely explanation is that she had an annuity which produced a small income.

As Mary Ann’s grandmother, Ann Ducro, had independent means, perhaps this income

passed had to her daughter, Mary, and on her to death, to her daughters. It would

explain how three generations of Steward ladies were able to live in relative comfort

pursuing occupations that were known for paying relatively poor wages. Certainly,

there do not appear to have been any relatives who were capable of supporting Mary

financially.  Although Mary’s sister and brother-in-law, Eliza and Jesse Fisher, had

enjoyed a relatively good standard of living, they had fallen on hard times and were

living in an Almshouse in Wood Green. Mary’s other sister, Esther, would also be

in a workhouse ten years later. Whatever the case, Mary Ann remained fit and healthy

enough to live at Elder Street until her death on 20 September 1893 of natural causes.

Present at the death was her niece, Emily Fowle (née Hockerday). Emily was the daughter

of Esther Steward, Mary’s sister, by Thomas Hockerday. At the time of Mary’s death,

Esther was living with Emily and her family in Hackney, so it was clear that the

family kept in touch.

Although Mary’s sister and brother-in-law, Eliza and Jesse Fisher, had

enjoyed a relatively good standard of living, they had fallen on hard times and were

living in an Almshouse in Wood Green. Mary’s other sister, Esther, would also be

in a workhouse ten years later. Whatever the case, Mary Ann remained fit and healthy

enough to live at Elder Street until her death on 20 September 1893 of natural causes.

Present at the death was her niece, Emily Fowle (née Hockerday). Emily was the daughter

of Esther Steward, Mary’s sister, by Thomas Hockerday. At the time of Mary’s death,

Esther was living with Emily and her family in Hackney, so it was clear that the

family kept in touch.

Two weeks after her death, probate was granted. It shows that her estate was valued

at £132 11s 8d — t he equivalent of almost two years’ wages for a craftsman at that

time. Although not a fortune, it shows a capable and sensible woman who had been

able to live in modest comfort without a husband. She was certainly better off than

her married sisters.

he equivalent of almost two years’ wages for a craftsman at that

time. Although not a fortune, it shows a capable and sensible woman who had been

able to live in modest comfort without a husband. She was certainly better off than

her married sisters.

By the time of Mary’s death, the burial grounds of London’s churches were full and

no burials had taken place at Christ Church for over thirty years. As a result, Mary

could not be buried in the same turf as her ancestors and her actual place of burial

is unknown.

Eliza Steward was baptised on 2 May 1819 at Christ Church. She married Jess James

Fisher on 9 June 1839 at the Church of St John the Baptist, Hoxton. Jesse had been

born in 1816 in Clerkenwell to Jesse and Maria Ann (née Vanhagen) Fisher whilst his

parents were living at Baltic Street (situated between the Barbican and Old Street).

Like his father, Jesse was a poulterer. After their marriage, Jesse and Eliza lived

in Quaker Street in Spitalfields near to where Eliza had grown up. By the 1850s,

their business was thriving and the family moved to Brown Street near St George Hanover

Square. They continued to live there until at least 1871 with their seven children.

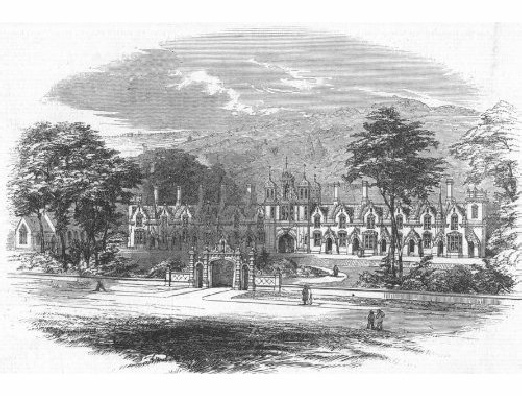

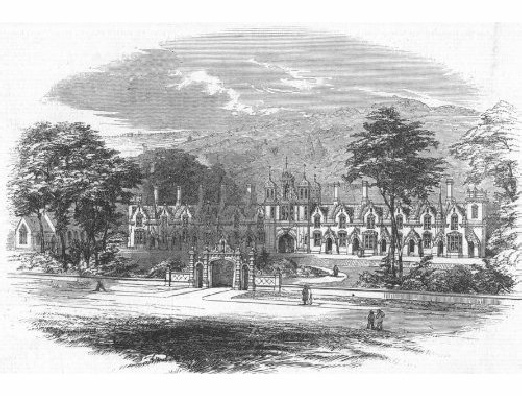

By about 1879, Eliza and Jesse had fallen on hard times. Fortunately, the Institution

of the Fishmongers and Poulterers’ Company provided assistance.  The Institution had

been established in 1835 and provided pensions and assistance to people in the trade

who were in reduced circumstances. In June 1847, work also began on the building

of a two-storey Tudor style almshouse in Wood Green (pictured on the right), one

of a number of institutes to choose Wood Green, which was favoured for its quiet,

rural surroundings. The almshouses were completed in 1850 and continued until the

early 1950s. Jesse and Eliza were given a house at the almshouse; one of only 12

houses available. They moved in shortly after the widow of the previous recipient

(John Marsh) died on 23 March 1879. Jesse and Eliza remained at number 11 until their

deaths: Eliza in 1893 and Jesse in 1897. Despite his reduced circumstances, Jesse

left £32 to his son, Thomas.

The Institution had

been established in 1835 and provided pensions and assistance to people in the trade

who were in reduced circumstances. In June 1847, work also began on the building

of a two-storey Tudor style almshouse in Wood Green (pictured on the right), one

of a number of institutes to choose Wood Green, which was favoured for its quiet,

rural surroundings. The almshouses were completed in 1850 and continued until the

early 1950s. Jesse and Eliza were given a house at the almshouse; one of only 12

houses available. They moved in shortly after the widow of the previous recipient

(John Marsh) died on 23 March 1879. Jesse and Eliza remained at number 11 until their

deaths: Eliza in 1893 and Jesse in 1897. Despite his reduced circumstances, Jesse

left £32 to his son, Thomas.

Mary Ann. Charles followed in 1815, Ann Martha in January

1817, Eliza in May 1819 and Esther in April 1821. In all, five daughters and a son.

As they grew up, the girls’ days were filled with learning those skills that they

would need, hopefully, as wives and mothers: running the house, cooking, washing

and needlework, as well as learning to read and write, no doubt a legancy of their

maternal Huguenot heritage.

Mary Ann. Charles followed in 1815, Ann Martha in January

1817, Eliza in May 1819 and Esther in April 1821. In all, five daughters and a son.

As they grew up, the girls’ days were filled with learning those skills that they

would need, hopefully, as wives and mothers: running the house, cooking, washing

and needlework, as well as learning to read and write, no doubt a legancy of their

maternal Huguenot heritage.  he ladies collected the materials and orders from their employer and

carried out the work at home, returning the finished garments and bonnets to their

employer at the appointed time. During this time, Mary Ann and Ann Martha were living

at 2 Wilkes Street in Spitalfields with their mother, Mary, and grandmother, Ann

Ducrow. It was a respectable address and made possible because of Ann Ducrow’s independent

income. Perhaps they worked in the garret room where the elongated windows allowed

the light to flood in. If so, and if they had glanced up, they would have seen the

familiar spire of Christ Church towering over them, the chimes of its bells regulating

their waking hours. The photographs show (above) the front door of 2 Wilkes Street

and (right) a view of Christ Church from the garret room. The map below shows Wilkes

Street (Wood Street) in about 1800.

he ladies collected the materials and orders from their employer and

carried out the work at home, returning the finished garments and bonnets to their

employer at the appointed time. During this time, Mary Ann and Ann Martha were living

at 2 Wilkes Street in Spitalfields with their mother, Mary, and grandmother, Ann

Ducrow. It was a respectable address and made possible because of Ann Ducrow’s independent

income. Perhaps they worked in the garret room where the elongated windows allowed

the light to flood in. If so, and if they had glanced up, they would have seen the

familiar spire of Christ Church towering over them, the chimes of its bells regulating

their waking hours. The photographs show (above) the front door of 2 Wilkes Street

and (right) a view of Christ Church from the garret room. The map below shows Wilkes

Street (Wood Street) in about 1800. n March 1845, Ann Ducro, then in her eighties, died. Presumably their grandmother’s

income ceased (although see below), and Mary Ann and Ann Martha left the faded gentility

of Wilkes Street and moved to a crowded house in Browns Lane (now Hanbury Street)

with their mother. Although it was only two streets away, it was a step down in the

world. The photograph on the left shows Hanbury Street in 1918, and the map below

shows its location.

n March 1845, Ann Ducro, then in her eighties, died. Presumably their grandmother’s

income ceased (although see below), and Mary Ann and Ann Martha left the faded gentility

of Wilkes Street and moved to a crowded house in Browns Lane (now Hanbury Street)

with their mother. Although it was only two streets away, it was a step down in the

world. The photograph on the left shows Hanbury Street in 1918, and the map below

shows its location. emand during the London society 'season', were often forced to supplement their

income in quieter months through prostitution, and London's fashionable Burlington

Arcade doubled as an upmarket red-

emand during the London society 'season', were often forced to supplement their

income in quieter months through prostitution, and London's fashionable Burlington

Arcade doubled as an upmarket red- two of whom were fur sewers and the other a bonnet shape maker

(the photograph on the right shows Princelet Street today).

two of whom were fur sewers and the other a bonnet shape maker

(the photograph on the right shows Princelet Street today).  the Police Commission

estimated that there were 62 brothels in Whitechapel and 1,200 prostitutes (the estimated

number of prostitutes in London varies from a modest 7,000 to a staggering 80,000

depending on whether it was the Police Department or the Society for the Suppression

of Vice who was doing the estimating; scholars believe the Society's guess may be

closer to the truth, which would equate to more than one prostitute for every twelve

adult males in Greater London in the mid-

the Police Commission

estimated that there were 62 brothels in Whitechapel and 1,200 prostitutes (the estimated

number of prostitutes in London varies from a modest 7,000 to a staggering 80,000

depending on whether it was the Police Department or the Society for the Suppression

of Vice who was doing the estimating; scholars believe the Society's guess may be

closer to the truth, which would equate to more than one prostitute for every twelve

adult males in Greater London in the mid-

Although Mary’s sister and brother-

Although Mary’s sister and brother- he equivalent of almost two years’ wages for a craftsman at that

time. Although not a fortune, it shows a capable and sensible woman who had been

able to live in modest comfort without a husband. She was certainly better off than

her married sisters.

he equivalent of almost two years’ wages for a craftsman at that

time. Although not a fortune, it shows a capable and sensible woman who had been

able to live in modest comfort without a husband. She was certainly better off than

her married sisters.  The Institution had

been established in 1835 and provided pensions and assistance to people in the trade

who were in reduced circumstances. In June 1847, work also began on the building

of a two-

The Institution had

been established in 1835 and provided pensions and assistance to people in the trade

who were in reduced circumstances. In June 1847, work also began on the building

of a two-