james george bostock (1846-

Early years

James George was born on Friday 27 November 1846 at 5 Hackney Road in Shoreditch, the son of George and Esther Bostock (née Steward). Unlike his siblings, who were baptised at the Church of St Leonard, James George was baptised at the Church of St John the Baptist. Although further from 5 Hackney Road than St Leonard’s, it is unlikely that the family had moved nearer to this church, as they had lived at either 5 or 11 Hackney Road for many years. Certainly in 1851, James George was living with his grandmother, parents, uncle and three siblings at 11 Hackney Road, whilst his brother, Edwin Francis, was born a year later at number 5.

A difficult start

It may not have been the happiest of childhoods; in 1853, when James George was only seven years old, his father died. James George and his mother and siblings continued to live with his grandmother, Marie Antoinette Bostock, and when his mother left to live with a carpenter by the name of Thomas Hockerday in about 1857, James George remained with his grandmother. This arrangement continued during the years that James George was learning his trade, although Esther kept in contact with her children, later acting as a witness at the marriage of her grandson, Edwin Francis, in 1899.

The Bostock family were artisans and included carpenters, plasterers, paper hangers and stencillers, and James George decided to follow in his father’s footsteps and train as a cabinet making. Shoreditch and Hackney were the centre of the furniture trade; the opening of the Regents Canal in 1820 had made the transport of timber cheaper and easier, and Shoreditch was close enough to trade with the City but far enough away to keep rents at a reasonable level. By 1861, about a third of all London furniture makers worked in the east end. According to The Book of Trade or Library of Useful Art, ‘a young man brought up to this business should possess a good share of ingenuity, and talents for drawing and designing’.

By the late 1860s he had learnt his trade. By 1870 he was living with Mary Ann Hockerday.

She was the daughter of Thomas Hockerday whom James George’s mother had been living

with since about 1857, making her James George’s step-

The slums of Bethnal Green

On 25 October 1870, James George and Mary Ann’s first child, George, was born at

87 Hollybush Gardens in Bethnal Green. The following year they were living at 6 Pundersons

Gardens. Both ‘Garden’ addresses s ound idyllic, but names can be deceptive. At the

start of the nineteenth century, Bethnal Green had been a mixture of buildings, market-

ound idyllic, but names can be deceptive. At the

start of the nineteenth century, Bethnal Green had been a mixture of buildings, market-

Yet there were improvements and in 1871 the Improved Industrial Dwellings Company

bought up 9 acres on which it built terraces of 'breakfast-

From Pundersons Gardens, James George and Mary Ann moved to 11 Gibraltar Walk (pictured

below). An article in The Builder from 1871, written after a visit to B ethnal Green,

commented that in the street were ‘brokers, furniture-

ethnal Green,

commented that in the street were ‘brokers, furniture-

Most of Mary Ann and James George’s children were baptised at the Church of St James the Great. This was one of the many new churches built from the 1840s to administer to the booming population, designed not only to bring spiritual succour to the ungodly of the east end but also to improve its morals and social welfare.

Despite the generally poor conditions and the severe overcrowding in Bethnal Green,

the location served the needs of both James George and Mary Ann: James George as

a cabinet maker and Mary Ann as a silk weaver. In 1872 nearly 700 addresses in Bethnal

Green were connected with the furniture industry, compared with 85 in Hackney and

659 in Shoreditch. Many of these addresses were small-

An unexpected move

For a brief period in 1881, James George and his family  moved to 43 Cullum Street

in West Ham. It is an unusual occurrence in an otherwise familiar pattern, but there

can be no doubt. Whatever the reasons, by May 1883 James George and Mary Ann were

back on the familiar turf of Bethnal Green and although no death certificate has

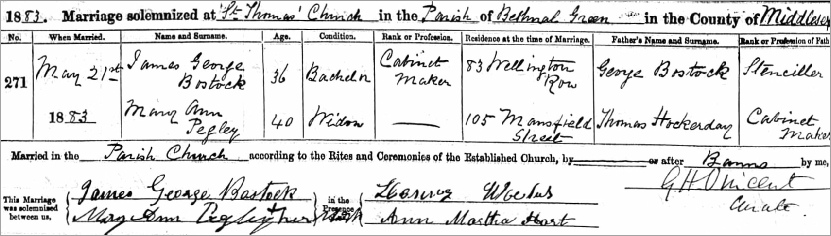

been found for Henry Pegley, James George married Mary Ann on 21 May 1883 at the

Church of St Thomas, witnessed by James George’s sister, Ann Martha. James George

is recorded as a 36 year-

moved to 43 Cullum Street

in West Ham. It is an unusual occurrence in an otherwise familiar pattern, but there

can be no doubt. Whatever the reasons, by May 1883 James George and Mary Ann were

back on the familiar turf of Bethnal Green and although no death certificate has

been found for Henry Pegley, James George married Mary Ann on 21 May 1883 at the

Church of St Thomas, witnessed by James George’s sister, Ann Martha. James George

is recorded as a 36 year-

One significant move in a lifetime was enough and in 1891, James George and Mary Ann were living at Garden Place, with their seven children, the three eldest of whom, James, George and Albert, were cabinet makers like their father.

Failing health

By 1900, James George started to suffer from various complaints, and over the next

decade was a patient in the Shoreditch infirmary on a number of occasions. The Infirmary

was in a building adjoining the Workhouse, and although an annexe had been built

in 1884, in 1901 when James was admitted it was far from an exemplar of modern nursing.

A report by The British Medical Journal in 1899 had commented on its under-

James George was admitted again on 24 January 1903 and remained in hospital until 15 June 1903 when he discharged himself. A month later, on 17 July 1903 he returned, suffering from rheumatism. He was kept in the infirmary for four days and was discharged to the Workhouse. A year later, in late November 1904, he spent three weeks in the infirmary suffering from gout, and was discharged just before Christmas on 20 December 1904.

![]()

A decline in fortunes

After these bouts of illness, life went from bad to worse for James George. An attack

on his wife in 1909 resulted in her being admitted to a mental asylum. Now in his

60s, James George was admitted regularly to the Workhouse. Sometimes his stays lasted

one or two nights, but on other occasions he remained an inmate for weeks at a time.

On most occasions, in the space for ‘place from where admitted’, the Creed register

notes ‘no home’. During this period, the assistant matron of the Shoreditch Infirmary

was a nurse by the name of Edith Cavell. After leaving Shoreditch she travelled to

Brussels, remaining there when the First World War broke out. In October 1915, news

reached Britain that she had been executed by the Germans, wearing her nurses uniform,

for helping British soldiers escape German- emembered the

dedicated matron.

emembered the

dedicated matron.

By 1916, the length of time that James George remained in the Workhouse began to increase and he was an inmate from 8 April 1916 to 23 March 1917. The Workhouse Registers show James George’s next of kin (or ‘address of friends’ at it was termed) was his daughter, Esther Golding. Between 1908 and 1917, Esther moved at least twice, indicating that James George was in contact with her; perhaps he lived with her, or one of his other children, during the periods he was not an inmate in the Workhouse.

Why, if he was in contact with his family, was he an inmate in the workhouse on so

many occasions? Family rifts or illness may have prevented his children from looking

after him, he may not have wanted to burden his family, or his family may have been

financial incapable of supporting him. Often children were too poor to take care

of elderly relatives, particularly if they need significant care; the photograph

below shows a house in Brownlow Road, probably similar to the house that Esther Golding

rented. To twenty-

Another possible explanation for James George’s situation was provided by his granddaughter, Irene. According to her, James George had taken over the family business after his father, George died, running it until the early twentieth century. As he approached retirement, his family argued over who should look after him and what would become of his business: the ensuing arguments divided the family. Irene recounted that James George’s response was to give away his possessions and throw himself on the mercy on the workhouse.

There are some difficulties with this story: James George was only eight years old

when his father died, and there is no evidence that either he or his mother, Esther

Bostock, was left an inheritance in James Bostock’s Will of 1859 (indeed, as Esther

was living with Thomas Hockerday by this date it is unlikely that she received anything).

However, like many family stories, there may be some truth in it, and it is more

likely that James George’s frequent stays in the Workhouse point to family  tensions

and disagreements, as well as difficult financial circumstances of which they were

somewhat ashamed.

tensions

and disagreements, as well as difficult financial circumstances of which they were

somewhat ashamed.

Whatever the truth of the matter, James George was saved from an old age as a workhouse

inmate by his eldest son, James, and daughter-

His new surroundings suited James George; his health improved and he remained fit and active. In the winter of 1930, he developed bronchitis and was admitted to Central Home in Leytonstone. Up until the First World War, this had been the West Ham Union Workhouse but from 1930 control had passed to West Ham County Council and it was used as a home for the chronically sick, aged and infirm. It was here that James George died on 18 January 1931 from acute bronchitis.

who’s related to whom

james bostock

(circa 1770)

james george bostock

(1846-

m

living moss

(born 1947)

living moss

(born 1968)

may alexandra bostock

(1911-

| paternal tree |

| maternal tree |

| index of names |

| monger photos |

| moss photos |

| collins photos |

| bostock photos |

| george moss |

| william moss |

| george c moss |

| eleanor evans |

| gregory family |

| thomas gregory |

| thomas gregory |

| sissey family |

| christopher sissey |

| sissey children |

| brisco family |

| william briscoe |

| john biscoe |

| susan webb |

| briscoe children |

| betsy biscoe |

| james bostock |

| george bostock |

| james g bostock |

| edwin f bostock |

| may bostock |

| marie wicks & sarah homan |

| homan bostock family |

| steward family |

| charles steward |

| ducro family |

| esther steward |

| mary & ann steward |

| stephen ducro |

| mary ducro |

| Ann_Briggs |

| hockerday family |

| thomas hockaday |

| mary ann hockerday |

| peters family |

| william peters |

| joseph peters |

| emily a peters |

| joseph collins |

| samuel collins |

| joseph collins |

| henry j collins |

| florence a collins |

| william shepherd |

| ann e shepherd |

| rogers family |

| john rogers |

| sarah a rogers |

| harvey family |

| thomas harvey |

| ann harvey |

| grigg family |

| william monger |

| charles monger |

| george monger |

| albert j monger |

| benham family |

| thomas benham |

| mary a benham |

| stephen dunford |

| fanny dunford |

| cawte family |

| robert cawte |

| william cawte |

| john r cawte |

| reynolds family |

| william reynolds |

| emma reynolds |