Early years

Thomas Harvey was born in about 1799 probably in the West Midlands around Oldbury.

Like most children of working-class families, he received no more than a year or

two of schooling and could not read or write. By about the age of eight, he was most

likely working at the local pit.

The coal mining and iron working industries developed rapidly from the end of the

eighteenth century as new technology made deep cast mining possible. The industry

employed men and women from as young as about six. Children began by carrying broken

picks to the smith to be repaired, helping to empty the skips that were sent up to

the coal face, running errands, or controlling the air doors in the pit, or filing

sacks with coal. There was always work to do; the day was long and hard and no one

went idle. After a couple of years, Thomas took up heavier work such as pushing the

carts in the pit, and by about age 12, he was most likely wielding a pick, quickly

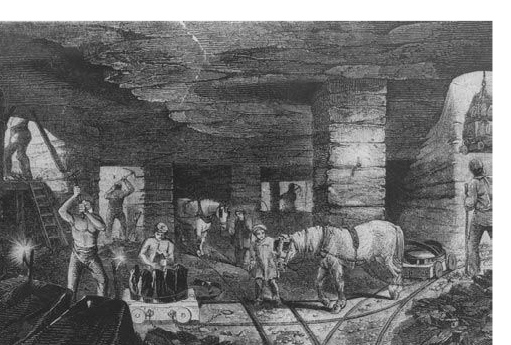

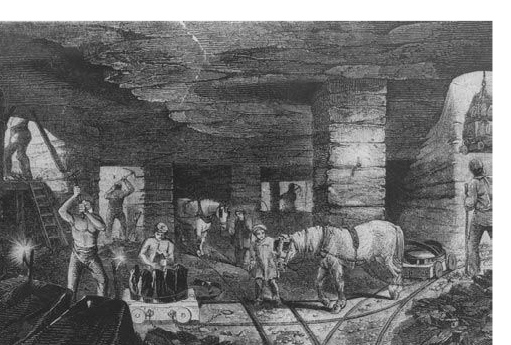

building up his strength and learning how to cut the coal seam. The illustration

on the right shows the Bradley Mine near Bilston in the early nineteenth century.

Down the mine

The working day started at six in the morning and finished at six at night. It was

hard, physical work. An account of 1842 describes how the holer or hewer would ‘lay

himself on his side and holding his pick in both hands strikes against it (the seam)

with all his force, throwing all the weight of his body into the blow and brings

out the coals. A day’s work of a pickman is one yard six inches in front and two

yards inwards, and two feet high’. There was an hour for lunch down the pit, in an

large area cut out for the purpose. A Royal Commission of 1842, set up to look at

conditions in the mines, particularly in relation to child labour, paints a vivid

picture of the lunchtime break:

“It is a fine sight to see the miners congregated at dinner, in a large dining hall

cut out of the coal. There they sit, naked from the middle upwards, as black as blackamoor

savages, showing their fine, vigorous, muscular persons, eating, drinking, and laughing.

They sit an hour and then resume their labours.”

Thomas’ lunch would have been brought to the pit bound up in a handkerchief by one

of his relatives. Everything was loaded into a skip and sent down the shaft; each

man knew his dinner by the pattern of the handkerchief in which the food was wrapped.

The mine provided a quart of pit beer to accompany the meal, and another quart at

the end of the day, when Thomas and his fellow miners ascended the pit into the room

lit by a fire.  The depth of the mines meant that the men were a constant warm temperature

and miners escaped the cold, rain, snow and frost until they emerged above ground

at the end of their twelve-hour shift.

The depth of the mines meant that the men were a constant warm temperature

and miners escaped the cold, rain, snow and frost until they emerged above ground

at the end of their twelve-hour shift.

The working week was six-days long, although work finished early on a Saturday and

there might also be a ‘holiday’ once a fortnight. Saturday was the day for a good

wash with hot soap and water, and Sunday the day for chapel or church, lunch and

then a rest in the afternoon followed by a walk or a lie down on the grass to soak

up the sunlight. The Commission noted that leisure time was spent, ‘chiefly in the

public-houses, drinking beer, and singing and dancing the double shuffle, to the

music of the fiddle or hurdy-gurdy. The noise of the shoes is the source of delight

in this dance and the hobnails of the colliers afford great advantage. Sometimes

in summer they will sit all round the door of the public-house in a great circle

all on their hams and every man his bull-dog between his knees and in this they position

they drink and smoke’.

Married life

Whether Thomas meat Sarah Grigg in the public-house or the church, they were married

on 13 December 1824 at the Parish church in Dudley. From Dudley, Thomas and Sarah

moved to Oldbury. A son, Joseph, was born not long after, followed by four daughters:

Mary (circa 1828), Ann (circa 1823), Elizabeth (circa 1834) and Sarah (circa 1835).

There may have been other children between 1823 and 1834 who did not survive infancy:

in the West Midlands, almost one in two children died under the age of three; one

of the worst records of infant mortality in England.

During this time, Thomas and his family continued to live in Oldbury and in 1841

were at Shidas Road. Thomas continued working as a miner. It was a dangerous job

and miners could expect at least one injury at some time during their working lives.

Just how dangerous was proved on Tuesday 17 November 1846. Just before six o’clock,

Thomas left for work as usual. Not long after, at about 6.45am, the ground shook

and there was a huge explosion. In a town where a quarter of the population were

employed by the mines, Sarah did not need to ask the cause: pit explosions happened

all too frequently. Sarah rushed to the pit together with the people of Olbury (reportedly

in their thousands), to be met by the sight of clouds of sulphurous vapour and flames

leaping from the shaft. It took all day to remove the horribly burned bodies and,

as each body was brought out, the crowd surged, trying to see if the victims were

husbands, fathers, brothers or uncles. In all, nineteen bodies were recovered; five

miners also had terrible injuries and four escaped unharmed. Thomas was probably

working for another colliery, but Sarah would have looked on in the realisation that

it could have easily have been her husband instead of those of her neighbours. The

bodies were taken home by cart and a local newspaper account added, “It is difficult

to imagine the sight of such horribly burned bodies lying at home, perhaps for days

before burial”.

The inherent dangers of mining meant that miners were well paid compared to workers

in other branches of industry. On average, boys working in the mines earned two or

three times the wage of other boys their age, and by the age of fourteen might be

earning 15s a week (1842). Certainly in 1851, Thomas’ wage was supporting his wife,

Sarah, and their daughter, Ann Brown (already widowed by the age of 22) and her infant

daughter, Betsy. His son, Joseph, also a miner, was living at home with his young

wife, Elizabeth.

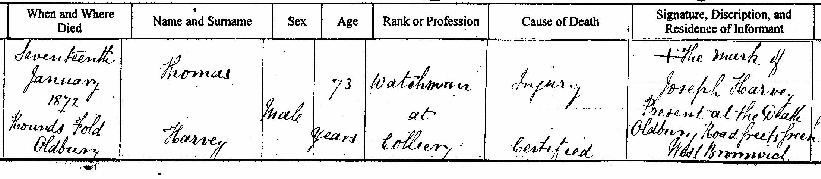

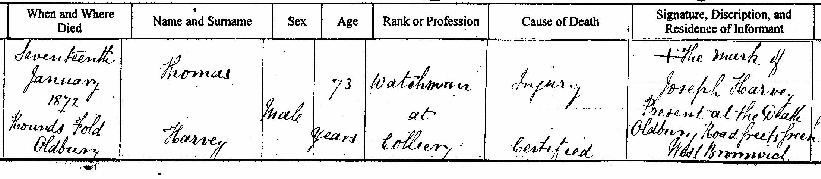

Thomas continued working as a miner and in 1861 was still living in Oldbury with

Sarah. His daughter, Ann, had remarried and was living next door with her husband,

John Rogers, and their five children. Thomas remained in Rounds Fold in Oldbury,

although by the mid-1860s work became too physically demanding and the 1871 census

records him as having ‘no occupation’. Not long after, he started working at the

colliery as a watchman. On 17 January 1872 he was injured, presumably at work, and

died as a result of his injuries, although his death certificate does not provide

any further information. The dangers of mining were not just below ground and colliery

records document the deaths of watchmen from causes as diverse as falling through

a hatch and being hit by a gate during bad weather.

The depth of the mines meant that the men were a constant warm temperature

and miners escaped the cold, rain, snow and frost until they emerged above ground

at the end of their twelve-

The depth of the mines meant that the men were a constant warm temperature

and miners escaped the cold, rain, snow and frost until they emerged above ground

at the end of their twelve-