Early years

About two months after the remnants of Napoleon’s Grand Army had retreated from Moscow

in the winter of 1812, in the sleepy Hampshire village of Preston Andover Mary Benham

gave birth to a son who she and her husband, William, named Thomas. He was probably

one of the last children of a large family which had begun in 1802 with a brother,

William. T homas was baptised on 7 March 1813 at the medieval Church of St Mary the

Virgin at Preston Candover, where at least three of the Benham children had been

baptised earlier that century. This ancient church had been founded in about 1190,

although largely rebuilt after a fire of 1681; all that remains today is the chancel

(pictured left), the rest of the church having been demolished in 1884 when a new

church was built in the village.

homas was baptised on 7 March 1813 at the medieval Church of St Mary the

Virgin at Preston Candover, where at least three of the Benham children had been

baptised earlier that century. This ancient church had been founded in about 1190,

although largely rebuilt after a fire of 1681; all that remains today is the chancel

(pictured left), the rest of the church having been demolished in 1884 when a new

church was built in the village.

Preston Candover is of Saxon origin, and its name derives in part from the Candover

Brook which rises from springs just to the south of the village. It was a farming

community, although by 1820, nearly four-fifths of the land was held by three landowners,

a result of the Enclosure Act. This Act had resulted in the strips of common land,

which had been farmed for generations by the local population, being swept away and

the open arable fields and pasture carved up into large rectangular fields.

Thomas’s father, William, like most of the population of Hampshire, at that time,

was an agricultural labourer. In rural Britain, the land provided nearly every form

of employment, from labourer to carter, blacksmith to shepherd, farmer to land owner,

and its gentle rhythms dictated all aspects of life. From an early age, Thomas worked

on the land, especially at haymaking when all hands were needed, and so by his early

teens, Thomas had grown into, rather than chosen to become, an agricultural labourer,

in the same way his father had done and probably his fathers before him. As a child,

the family moved in search of work, usually to the next village or farm, dictated

by who was hiring and the vagaries of the weather which ultimately dictated the size

of the crop.

An honest wage

The 1820s were a difficult period for workers. The agricultural revolution, especially

enclosure, upset traditional rural society. There was a shift from self-sufficient,

open-field villages to farms  rented by tenant farmers employing labourers. Hiring

was on a casual basis and it became more common for labourers to be paid by the day

or week or by results, and to be employed for short periods for harvesting, hedging,

ditching, threshing, and so on. 'Living in' disappeared and farmhands were transformed

into casual labourers with no guarantee of work. There was a surplus of labour and

pay declined. In 1830 a series of agricultural disturbances known as the Swing Riots

swept across much of southern England. The rioters acted against farmers who kept

wages low and used threshing machines which deprived labourers of winter work. In

Hampshire the riots lasted about a week and ended with three men being hanged in

Winchester and over a hundred being transported to Australia.

rented by tenant farmers employing labourers. Hiring

was on a casual basis and it became more common for labourers to be paid by the day

or week or by results, and to be employed for short periods for harvesting, hedging,

ditching, threshing, and so on. 'Living in' disappeared and farmhands were transformed

into casual labourers with no guarantee of work. There was a surplus of labour and

pay declined. In 1830 a series of agricultural disturbances known as the Swing Riots

swept across much of southern England. The rioters acted against farmers who kept

wages low and used threshing machines which deprived labourers of winter work. In

Hampshire the riots lasted about a week and ended with three men being hanged in

Winchester and over a hundred being transported to Australia.

At about this time, Thomas was living near Overton, a larger village a few miles

north west of Preston Candover. During this period of unrest, several hundred labourers

marched through Overton demanding money, food and higher wages; perhaps Thomas was

one of them. Prompt negotiations with local farmers resulted in a settlement. It

was whilst Thomas was living at Overton that Thomas met Francis (‘Fanny’) Durnford

(or Dunford). Fanny was a local girl who had been born around Overton in about 1813.

On Thursday, 18 July 1833 they walked to the Church of St Mary (pictured above) where

they were married. Fanny’s sister and brother-in-law, Elizabeth and John Green, joined

them and acted as their witnesses. All of the wedding party made their mark. About

a year and half later, in 1835, Thomas and Fanny’s son, Stephen was born while the

family were living in Overton; another son, William, followed a few years later.

In search of work

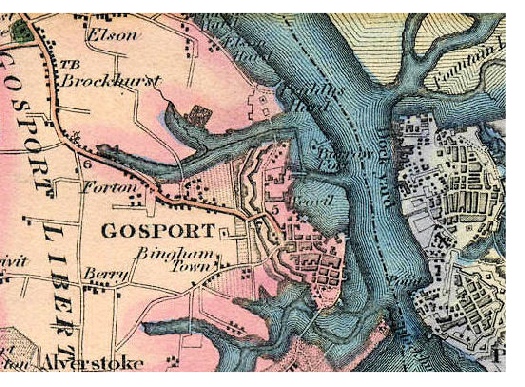

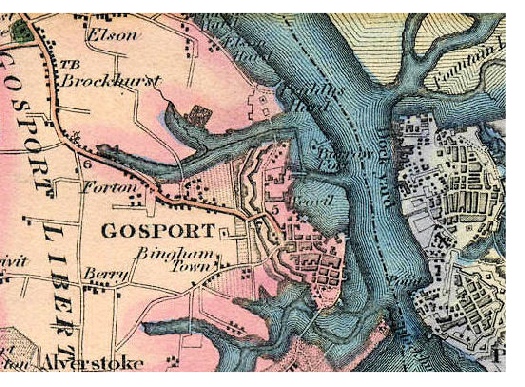

From the late 1830s, railways started to spring up all over the country, and one

of the first to be built in Hampshire ran from Bishopstoke to Gosport. It was authorised

in 1839 and during 1840, perhaps after harvesting when agricultural labourers were

in less demand, Thomas and Fanny travelled south to  work as labourers on the railways.

The 1841 census shows they were living in Brockhurst, outside Gosport where a station

was built. It must have been a difficult decision to leave two young children behind;

their son, Stephen, remained with Thomas’ parents in Overton; William may have been

left with another relative. By November 1841, when the railway was opened, Thomas

and Fanny were back in Nutley where their daughter, Mary Ann, was born on 22 January

1844. By 1851 census, the family had returned to Preston Candover; sharing the house

with Thomas and Fanny were their three children, Fanny’s elderly uncle, Thomas Brown,

who had been born in Andover, and a 22-year old lodger from Nutley called Daniel

Goodyear.

work as labourers on the railways.

The 1841 census shows they were living in Brockhurst, outside Gosport where a station

was built. It must have been a difficult decision to leave two young children behind;

their son, Stephen, remained with Thomas’ parents in Overton; William may have been

left with another relative. By November 1841, when the railway was opened, Thomas

and Fanny were back in Nutley where their daughter, Mary Ann, was born on 22 January

1844. By 1851 census, the family had returned to Preston Candover; sharing the house

with Thomas and Fanny were their three children, Fanny’s elderly uncle, Thomas Brown,

who had been born in Andover, and a 22-year old lodger from Nutley called Daniel

Goodyear.

White Hill Farm

Three years later in 1854 Thomas and Fanny were working at White Hill Farm. White

Hill runs from Kingsclere in the north, descending steeply to Overton in the south;

at its crown it provides spectacular views of the valley below, but is exposed to

the elements. In the Summer of 1853 Fanny gave birth to another daughter, Eliza.

Not long after, Fanny started coughing up blood. In the mid-nineteenth century consumption

killed one in five adults and both Thomas and Fanny would have recognised the symptoms.

Fanny died in February 1854 leaving Thomas a widow at the age of 41.

Five years later, on 5 March 1859, Thomas remarried at the Church of St Mary in Nutley.

Ann Marchant (née Dore) was the daughter of James Dore, a labourer, and had been

born in the Isle of Wight in 1820. Although her father had worked as a labourer,

she could read and write and by 1851 had moved to Winchester in Hampshire, where

she married a tailor called Henry Marchant in 1851. It was a brief marriage; her

husband died in the Summer of 1855.

she married a tailor called Henry Marchant in 1851. It was a brief marriage; her

husband died in the Summer of 1855.

In 1861 Thomas and his new wife were living on the Oxford Road in Preston Candover,

with Thomas’s seven-year old daughter, Eliza. The photograph on the right shows typical

cottages in the village. Thomas and Ann continued to live in Preston Candover for

another ten years. Thomas worked as a labourer and a sawyer (someone who saws timber

into boards), perhaps in the winter months to supplement their income when there

was less agricultural work to be done; Ann was working as a dressmaker.

Towards the end of November 1874, Thomas started experiencing fever and headaches.

His symptoms became rapidly worse and may have caused seizures, confusion or drowsiness.

He died on 13 December 1874; the doctor diagnosed the cause of death as encephalitis,

a rare viral infection that causes inflammation of the brain.

homas was baptised on 7 March 1813 at the medieval Church of St Mary the

Virgin at Preston Candover, where at least three of the Benham children had been

baptised earlier that century. This ancient church had been founded in about 1190,

although largely rebuilt after a fire of 1681; all that remains today is the chancel

(pictured left), the rest of the church having been demolished in 1884 when a new

church was built in the village.

homas was baptised on 7 March 1813 at the medieval Church of St Mary the

Virgin at Preston Candover, where at least three of the Benham children had been

baptised earlier that century. This ancient church had been founded in about 1190,

although largely rebuilt after a fire of 1681; all that remains today is the chancel

(pictured left), the rest of the church having been demolished in 1884 when a new

church was built in the village.  rented by tenant farmers employing labourers. Hiring

was on a casual basis and it became more common for labourers

rented by tenant farmers employing labourers. Hiring

was on a casual basis and it became more common for labourers work as labourers on the railways.

The 1841 census shows they were living in Brockhurst, outside Gosport where a station

was built. It must have been a difficult decision to leave two young children behind;

their son, Stephen, remained with Thomas’ parents in Overton; William may have been

left with another relative. By November 1841, when the railway was opened, Thomas

and Fanny were back in Nutley where their daughter, Mary Ann, was born on 22 January

1844. By 1851 census, the family had returned to Preston Candover; sharing the house

with Thomas and Fanny were their three children, Fanny’s elderly uncle, Thomas Brown,

who had been born in Andover, and a 22-

work as labourers on the railways.

The 1841 census shows they were living in Brockhurst, outside Gosport where a station

was built. It must have been a difficult decision to leave two young children behind;

their son, Stephen, remained with Thomas’ parents in Overton; William may have been

left with another relative. By November 1841, when the railway was opened, Thomas

and Fanny were back in Nutley where their daughter, Mary Ann, was born on 22 January

1844. By 1851 census, the family had returned to Preston Candover; sharing the house

with Thomas and Fanny were their three children, Fanny’s elderly uncle, Thomas Brown,

who had been born in Andover, and a 22- she married a tailor called Henry Marchant in 1851. It was a brief marriage; her

husband died in the Summer of 1855.

she married a tailor called Henry Marchant in 1851. It was a brief marriage; her

husband died in the Summer of 1855.