samuel collins (1807-

Early years

Samuel Collins was born in the Spring of 1807 in Wavendon in Buckinghamshire. A few weeks after Easter on Sunday 12 April, his parents, Joseph and Honour, carried him to the parish church of St Mary where he was baptised. He was born into and grew up in a rural community and, like most children from labouring families, he worked from a young age, running errands, clearing stones, chasing birds from crops and helping at harvest time.

The period from 1750-

The move south

London was only fifty miles from Wavendon but Samuel had most likely never travelled

such a distance. Whilst there had been great improvements in the roads in the previous

century, road travel was still slow and greatly influenced by the weather. Taking

advantage of the first spell of dry Spring weather, Samuel headed south, walking

the mile or so to Woburn from where Watling Street, the old Roman road,  travelled

in a near-

travelled

in a near-

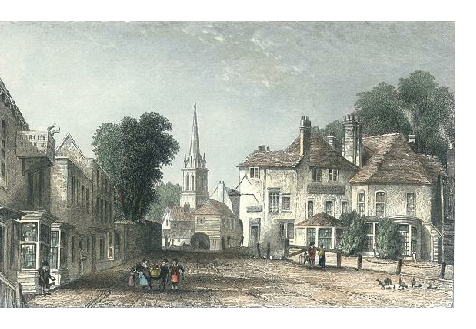

Whichever route he took, he must have felt a sense of relief and exhilaration when he caught sight of his first glimpse of London spreading out before him from the heights of Highgate and Hampstead, the dome of St Paul’s visible on the horizon (it can be seen in this painting of about 1800, a third of the way from the left).

Highgate

With its elevated situation, bracing air and fine views across London, Highgate had

been a popular location with the rich and sometimes the famous since the sixteenth

century; when Samuel arrived, the poet, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, had been living

there since 1817 and was known as ‘the sage of Highgate’. Originally centred around

the High Street, by 1800 Highgate had taken on a straggling appearance, stretching

from the Archway (or gate house from whence High-

Apart from the obvious attractions of Highgate, there are two other reasons why Samuel chose to settle here. Thomas Collins, born in Wavendon in about 1799, had been living in Highgate since at least 1829. He was certainly related to Samuel and may have been a brother, cousin, or uncle. If Samuel did not travel to London with Thomas, he most likely decided to settle in Highgate because of him.

Another reason for the Collins’ families choosing to live in Highgate was that it

and neighbouring Finchley were home to a number of non-

Married life

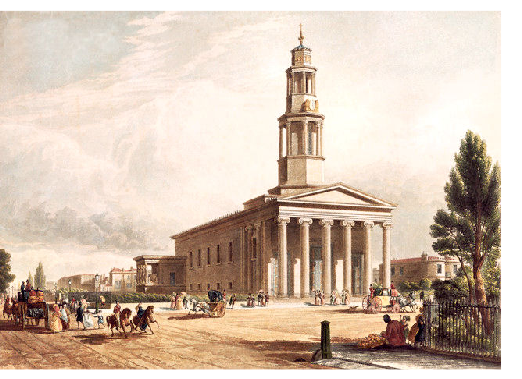

Sometime after moving to Highgate, Samuel met Mary Ann Harris, a local girl about

five years his senior. In 1830, the Church of St Michael in Highgate had not yet

been built, so on Sunday 12 December 1830, Samuel and Mary made their way to the

parish church of St Pancras, three miles away, shown below in an illustration of

1822. It was worth the journey: St Pancras is one of the most beautiful churches

in London, a nd, after St Paul’s Cathedral, the most expensive ever to be built. By

this time, Samuel may have become accustomed to the sights of London but he must

have been struck by the impressive façade and, if he’d had the slightest notion of

ancient Greece, would have thought he was entering an ancient Greek temple rather

than a recently built Protestant Church on a busy London thoroughfare. As for Mary,

at the age of 28, perhaps she was oblivious to the four stone caryatids supporting

the north portico, intent only on entering a church for her own wedding rather than

that of someone else. The marriage register shows that Samuel ‘made his mark’; Mary

Ann signed her name.

nd, after St Paul’s Cathedral, the most expensive ever to be built. By

this time, Samuel may have become accustomed to the sights of London but he must

have been struck by the impressive façade and, if he’d had the slightest notion of

ancient Greece, would have thought he was entering an ancient Greek temple rather

than a recently built Protestant Church on a busy London thoroughfare. As for Mary,

at the age of 28, perhaps she was oblivious to the four stone caryatids supporting

the north portico, intent only on entering a church for her own wedding rather than

that of someone else. The marriage register shows that Samuel ‘made his mark’; Mary

Ann signed her name.

A child, probably their first, was born around September 1834 and named Joseph after

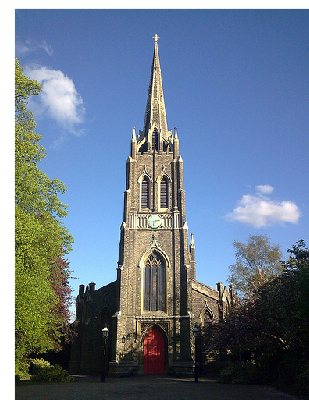

Samuel’s father. Fortunately for Samuel and Mary, a parish church — the Church of

St Michael, which stands higher than any other church in L ondon (pictured in the

photograph below and in the illustration from about this time) — had been consecrated

on 8 November 1832. So the walk to church on 12 October 1834 to have their son baptised

was a short one, less than a mile down North Hill to Highgate village. The church

would have been a startling sight, being an early example of the neo-

ondon (pictured in the

photograph below and in the illustration from about this time) — had been consecrated

on 8 November 1832. So the walk to church on 12 October 1834 to have their son baptised

was a short one, less than a mile down North Hill to Highgate village. The church

would have been a startling sight, being an early example of the neo-

A growing family

A few years after Joseph’s baptism, a daughter, Emma was born on 27 August 1837,

followed by William on 13 October 1839. Like their brother, they were baptised at

the Church of St Michael. Only a month after William’s birth, the two-

Her death might be considered a point of little interest at a time when the infant

mortality rate was one in four; what is interesting is her burial. Because of the

fear of contagion, she was buried  immediately -

immediately -

When she returned home, Mary Ann boiled, if not burnt, the bed linen and scrubbed

the house from floor to ceiling, such was the fear of infection spreading. At this

time, Samuel and his family may have been living at Wards Cottages on North Hill.

They were certainly living there by 1843 and had been living on North Hill at least

since 1841. Wards Cottages was a group of sixteen cottages situated about half-

Samuel and Mary Ann continued to live at Wards Cottages for another decade or so, and it was here that two more children were born: Samuel on Christmas Eve 1843, and Ann on 5 November 1847. They were baptised within a few weeks of their birth at the Church of St Michael. It was during this period that Samuel ceased working as a labourer and took up employment as a fishmonger. It must have provided a better income for the family and certainly been easier on Samuel.

Nevertheless, by 1853 Mary Ann’s health started to fail and she died a few days before

Christmas on  22 December 1853. The cause of death was given as dropsy, an out-

22 December 1853. The cause of death was given as dropsy, an out-

A second chance

Samuel did not stay a widower for long. Three months after Mary Ann’s death, on 3

April 1854, he married Charlotte March (née Rawlinson) at the Church of St Michael.

Charlotte was a 43-

In many regards, twenty-

Seven years after their marriage in 1861, Samuel and Charlotte were living in Highgate, and had taken in a lodger to help with the rent. Samuel was working as a fishmonger. Shortly before Christmas in 1865 Samuel died of chronic bronchitis. He was buried on 23 December 1865 at the Church of St Mary’s in Hornsey like his first wife, Mary Ann.

Postscript

Twice widowed and two days before Christmas, it was a bleak time for Charlotte. Nevertheless,

she continued to live at Wards Cottages, earning her living as a charwoman (that

is, a house cleaner). Living with her was her seventeen-

who’s related to whom

lilian jeanne monger

(1928-

living fenley

(born 1946)

living moss

(born 1968)

samuel collins

(1807-

mary ann harris

m

| paternal tree |

| maternal tree |

| index of names |

| monger photos |

| moss photos |

| collins photos |

| bostock photos |

| george moss |

| william moss |

| george c moss |

| eleanor evans |

| gregory family |

| thomas gregory |

| thomas gregory |

| sissey family |

| christopher sissey |

| sissey children |

| brisco family |

| william briscoe |

| john biscoe |

| susan webb |

| briscoe children |

| betsy biscoe |

| james bostock |

| george bostock |

| james g bostock |

| edwin f bostock |

| may bostock |

| marie wicks & sarah homan |

| homan bostock family |

| steward family |

| charles steward |

| ducro family |

| esther steward |

| mary & ann steward |

| stephen ducro |

| mary ducro |

| Ann_Briggs |

| hockerday family |

| thomas hockaday |

| mary ann hockerday |

| peters family |

| william peters |

| joseph peters |

| emily a peters |

| joseph collins |

| samuel collins |

| joseph collins |

| henry j collins |

| florence a collins |

| william shepherd |

| ann e shepherd |

| rogers family |

| john rogers |

| sarah a rogers |

| harvey family |

| thomas harvey |

| ann harvey |

| grigg family |

| william monger |

| charles monger |

| george monger |

| albert j monger |

| benham family |

| thomas benham |

| mary a benham |

| stephen dunford |

| fanny dunford |

| cawte family |

| robert cawte |

| william cawte |

| john r cawte |

| reynolds family |

| william reynolds |

| emma reynolds |