Early years

Sarah Ann was born on 15 March 1872 in Barrow-in-Furness in Lancashire, the youngest

child of John and Ann Rogers. Her father, a brickfield worker and labourer, was probably

working on the building of Ramsden Dock, as Sarah Ann was born at 14 Ramsden Dock

Cottages, a row of terraced houses just a stone’s throw from the Dock. She probably

spent the first few years of her life in Barrow, the masts of the ships visible from

the end of the road, and the plumes of smoke from the iron foundries visible from

her window. It was a busy town and the illustration below shows the docks in about

1890, although by this time, Sarah’s father had died, and Sarah and her mother had

moved south to Essex.

Bridgemarsh island

In 1881 Sarah Ann and her mother were living on Bridgemarsh island, an island situated

in the River Crouch in Essex. Although barely lying above sea level, in the eighteenth

century, it was drained, piled and enclosed by a sea wall, and was used for grazing

cattle and sheep, hunting the abundant wild duck, and catching eels which proliferated

in the internal dykes. A causeway was constructed from nearby Stamford Farm which

allowed access to the island at low tide.

In 1881 Sarah Ann and her mother were living on Bridgemarsh island, an island situated

in the River Crouch in Essex. Although barely lying above sea level, in the eighteenth

century, it was drained, piled and enclosed by a sea wall, and was used for grazing

cattle and sheep, hunting the abundant wild duck, and catching eels which proliferated

in the internal dykes. A causeway was constructed from nearby Stamford Farm which

allowed access to the island at low tide.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, a large brick and tile works sprung

up on the island, capitalising on the island’s clay deposits. This was one of a number

of brickworks which sprung up in the vicinity, spurred on by increased building.

However, Bridgemarsh island did not prove to be a viable site, and in 1892 the brickworks

was abandoned. In 1897 a bad flood breached the sea wall and part of the island was

lost permanently to the river; it eventually become uninhabitable in 1930. Today,

even on a fine day, Bridgemarsh island is a dreary spot, the flat, characterless

Essex landscape stretching to the horizon; on a cold, damp, grey day, it must have

been a punishing and bleak place to live. The photograph above shows the island is

the 1920s; the aerial photograph shows the island today, part of it submerged beneath

the river.

It was here that the nine-year old Sarah Ann years was living with her mother, and

her sister-in-law and her three daughters in April 1881: six Rogers women living

in accommodation described as ‘unoccupied on marsh’. There were 13 other people living

on the island including two brick makers, a dressmaker and a waterman. It is not

known how long the Rogers women lived on Bridgemarsh or where their men folk were

at the time of the 1881 census, but Sarah Ann lived here long enough to attend school

on the mainland, which she was rowed to by Henry Hubbard, the local waterman.

A move to civilisation

By 1889, Sarah Ann had left Bridgemarsh island and was living at 8 Piercefield Street

in St Pancras, London. It was a working class street on the northern boundaries of

Kentish Town, but the foot of Hampstead Hill was across the line of the nearby Hampstead

Junction Railway. This was the address that Sarah Ann gave when, on 23 December 1889,

she married Henry Joseph ‘Harry’ Collins at St Pancras’ Registrar’s Office. She gave

her age as 21, whilst Harry professed to be 22. In reality, Sarah Ann was 17 years

old and Harry was 19. Already about six months pregnant, Sarah Ann could not risk

being turned away by the Registrar on the grounds of being under age or marrying

without lack parental consent. But if the Registrar was doubtful of the ages that

Sarah Ann and Harry gave, he did not express it. Indeed, it was a common occurrence,

and he probably felt it was his moral duty to turn a blind eye and allow Sarah Ann

the security and respectability of marriage.

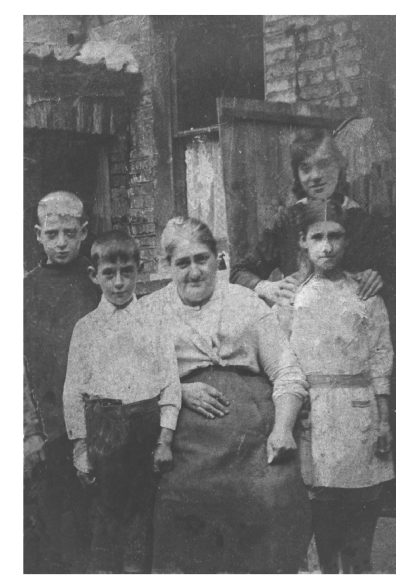

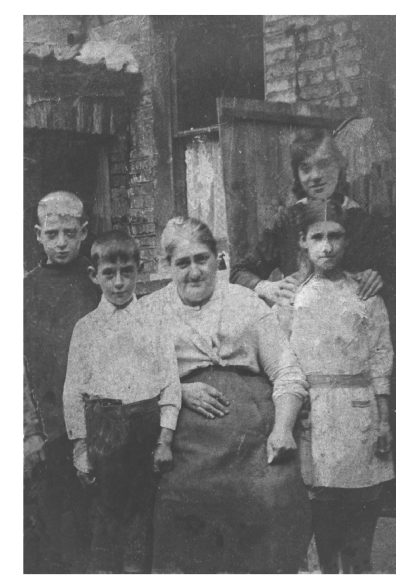

With a family growing at a rate of a child every 18 months, Sarah Ann’s life was

taken up with raising her children and taking care of the house. Like many working

class women, she took great pride in keeping her house and her family clean and tidy,

even if their clothes were mended and handed down from one child to the next. She

was particularly proud of her long hair, which turned white in old age, and which

her granddaughter, Lilian Monger, used to brush. Her granddaughter, Ruth, recalls

her being very smart and wearing a long blue dress, black stockings and black lace

up shoes with a clean white starched apron. The photograph below shows Sarah Ann

with four of her children. It was taken in the back yard of and may date to about

1914/15 when Ted Collins went to fight in the First World War.

Despite so many children, she also worked to supplement the family’s income. She

bought fruit and vegetables and would sell it around the streets from a wheelbarrow.

No doubt some of the profits were handed over the bar of the local pub as she liked

a drink and was often in the pub,  which she treated as an extension of her home;

she was known to sit there shelling peas into a colander. Before Harry came home

from work, one of the children would fetch her from the pub, often laying her on

the bed and putting vinegar rags on her forehead. They knew to tell their father

that their mother was ‘ill’ and had gone to bed. Harry was a sober man who never

drank, but if he suspected Sarah Ann’s fondness for a tipple, he did not let on.

which she treated as an extension of her home;

she was known to sit there shelling peas into a colander. Before Harry came home

from work, one of the children would fetch her from the pub, often laying her on

the bed and putting vinegar rags on her forehead. They knew to tell their father

that their mother was ‘ill’ and had gone to bed. Harry was a sober man who never

drank, but if he suspected Sarah Ann’s fondness for a tipple, he did not let on.

In November 1927, it must have come as a shock to Sarah Ann when her husband’s body

was carried home following a fatal injury at work.

Kith and kin

After Harry’s death, Sarah Ann lived with her various children, most of whom had

families of their own. Sometimes there was not enough space to stay with her children,

and then she would rent a room nearby. Her grandson, Bert Monger, recollected that

when she stayed with her daughter, Ada, in Battersea, Sarah rented a room at Mrs

Hyde’s who lived at number 67 or, when this was not available, at Dickie Thompson’s

house in Speke Road. Albert would help her walk round to her lodging, carrying her

stone water bottle while Sarah leaned on his shoulder. In the morning he would walk

her back to Ada’s house.

Sarah was not always a welcome visitor; whilst she was kind to her neighbours’ children,

she often caused trouble between her children and their spouses, taking sides and

interfering. The result was that no one kept her for very long. Not that she needed

an invitation. The Monger children recalled that when she turned up, they could tell

if she intended to stay by whether she had her feather mattress with her; on one

occasion, she arrived in a taxi with her rocking chair on the roof, pleading that

she had no where to live.

Her rocking chair was her prize possession. It marked her territory, even if it was

only the corner of a room in a crowded house, and it was where she hoarded items

such as papers and comics. She was not always a hindrance and would often cook dishes

which reflected her upbringing, such as rabbit pie or faggot stew. Albert Monger

recalled that faggot stew was usually cooked on Saturday. Sarah would send him to

Jolly’s, a butchers near Battersea High Street, to buy a sixpenny sheep’s head. Sarah

would cook it in a big iron pot with herbs, carrots and onions for a few hours. There

was always enough for two big helpings which filled everyone up so much they would

fall asleep. Sarah would put aside the sheep’s head, leaving it until a jelly formed

on the top, and then gnaw what was left. Cheap cuts of meat provided a good supply

of protein and was all most working class people could afford; Sarah was not squeamish

about what she ate and her grandchildren remember her eating chitterlings (pig’s

intestine).

After a life spent on the road, travelling around the country with her family, much

of it spent in the open air, she liked to pass the time sitting by the front door

talking to the neighbours. Conversation included the local gossip as well as picking

the names of horses on which to bet. After the start of the Second World War, she

went to live with her daughter, Ivy, in Mitcham. She died in Epsom Hospital in early

1942.

In 1881 Sarah Ann and her mother were living on Bridgemarsh island, an island situated

in the River Crouch in Essex. Although barely lying above sea level, in the eighteenth

century, it was drained, piled and enclosed by a sea wall, and was used for grazing

cattle and sheep, hunting the abundant wild duck, and catching eels which proliferated

in the internal dykes. A causeway was constructed from nearby Stamford Farm which

allowed access to the island at low tide.

In 1881 Sarah Ann and her mother were living on Bridgemarsh island, an island situated

in the River Crouch in Essex. Although barely lying above sea level, in the eighteenth

century, it was drained, piled and enclosed by a sea wall, and was used for grazing

cattle and sheep, hunting the abundant wild duck, and catching eels which proliferated

in the internal dykes. A causeway was constructed from nearby Stamford Farm which

allowed access to the island at low tide.

which she treated as an extension of her home;

she was known to sit there shelling peas into a colander. Before Harry came home

from work, one of the children would fetch her from the pub, often laying her on

the bed and putting vinegar rags on her forehead. They knew to tell their father

that their mother was ‘ill’ and had gone to bed. Harry was a sober man who never

drank, but if he suspected Sarah Ann’s fondness for a tipple, he did not let on.

which she treated as an extension of her home;

she was known to sit there shelling peas into a colander. Before Harry came home

from work, one of the children would fetch her from the pub, often laying her on

the bed and putting vinegar rags on her forehead. They knew to tell their father

that their mother was ‘ill’ and had gone to bed. Harry was a sober man who never

drank, but if he suspected Sarah Ann’s fondness for a tipple, he did not let on.