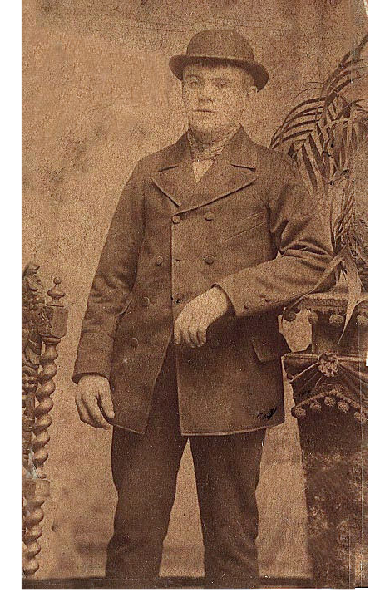

edwin francis bostock (1878-

Early years

The fifth of seven children born to James George Bostock and Mary Ann Hockerday,

Edwin Francis Bostock was born on 25 October 1878 at 11 Gibraltar Walk, Bethnal Green,

and baptised a few weeks later at the Church of St James the Great. In temperament

and looks he and his brother James were liked ‘two peas in a pod’: full of mischief

and fun with twinkling blue eyes, in contrast to his other siblings Albert, George

and Rosina who were more serious.

The fifth of seven children born to James George Bostock and Mary Ann Hockerday,

Edwin Francis Bostock was born on 25 October 1878 at 11 Gibraltar Walk, Bethnal Green,

and baptised a few weeks later at the Church of St James the Great. In temperament

and looks he and his brother James were liked ‘two peas in a pod’: full of mischief

and fun with twinkling blue eyes, in contrast to his other siblings Albert, George

and Rosina who were more serious.

Edwin Francis’ father and uncles were both cabinet makers and, after leaving school

in about 1892, it was natural for him to take up his father’s trade, learning his

craft in what may have been a family-

The girl next door

10 Emma Street, Haggerston was one of hundreds of terraced houses that had sprung

up in the last half of the nineteenth-

Edwin Francis married Emily on 7 August 1899 at the Church of St Stephen in Goldsmith’s

Row, Haggerston; the marriage was witnessed by his father, James George, and his

80- arriage, their first child, Edwin Francis Joseph, was born on

9 November 1903 in Walthamstow. In the following years, their family grew steadily.

James George was born on in July 1908 in Shoreditch, and May Alexandra followed on

2 April 1911 whilst Edwin and Emily were living at 38 Stanley Road, Stratford. Two

years later, George was born on 11 December 1913 at 11 Albert Terrace, Bromley-

arriage, their first child, Edwin Francis Joseph, was born on

9 November 1903 in Walthamstow. In the following years, their family grew steadily.

James George was born on in July 1908 in Shoreditch, and May Alexandra followed on

2 April 1911 whilst Edwin and Emily were living at 38 Stanley Road, Stratford. Two

years later, George was born on 11 December 1913 at 11 Albert Terrace, Bromley-

Looking at the children’s places of birth, it is clear that not only did Edwin Francis

and Emily moved regularly, as was common, but that they moved a greater distance

than many people, most of whom lived within a mile radius of their place of birth,

or less in some cases. Edwin Francis’ and Emily’s next move was in 1914 to 12 Franklin

Street in Bromley-

Answering the call

A power struggle of shifting alliances had long been building amongst the old imperial

powers of Europe, creating a tinder box that needed only a spark to ignite it. That

spark came on 28 June 1914 in Sarajevo when Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the

Austro- p, desperate not to miss out and buoyed up by the thought that ‘it

would all be over by Christmas’.

p, desperate not to miss out and buoyed up by the thought that ‘it

would all be over by Christmas’.

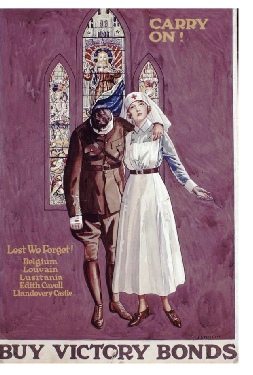

Although 36 years old with a wife and four young children, Edwin Francis enlisted. Did he feel it was his patriotic duty? Perhaps his friends had joined up, or he was spurred on by seeing one of the many recruiting marches? Or was he dazzled by the propaganda that promised adventure, or wanted to satisfy a wanderlust that his roaming in the East End of London could not cure. The reason may have been closer to home: in October 1915, word reached England of the execution of nurse Edith Cavell, the former ward sister at the Shoreditch Infirmary where Edwin’s father, James George, had been a patient. Whatever his motives, on 14 December 1914 he went to the recruiting office at Stratford and enlisted. Men had a choice of the regiment they joined; some men chose a regiment simply because they liked its badge or its uniform, or because of its reputation. Edwin Francis joined the King’s Royal Rifles Corp: perhaps he liked the thought of being Rifleman Bostock rather than plain Private Bostock; for a man who may have been looking for adventure, it sounded like something from a ‘Boys Own’ adventure story. Whatever the case, he drew himself up to his full 5 feet 3½ inches and was accepted; the minimum height requirement for joining the army was 5 foot 3 inches.

After accepting the King's Shilling, Edwin returned home to await his joining  instructions

and travel warrant. This arrived, and two days later he was in Winchester where he

joined his Battalion and was issued with his uniform and army kit. He spent the next

few months training and was posted to France on 14 April 1915.

instructions

and travel warrant. This arrived, and two days later he was in Winchester where he

joined his Battalion and was issued with his uniform and army kit. He spent the next

few months training and was posted to France on 14 April 1915.

Edwin served on the Western Front in France as part of the British Expeditionary Force. It is not known exactly where he was posted or what action he saw, but while he was in France the second battle of Ypres raged. The town was strategically important as a gateway to the sea ports, and in the late Spring of 1915, the conflict, which lasted little over a month, saw 95,000 casualties, almost 60,000 of them British. The following year saw the German attack on Verdun with equally heavy casualties.

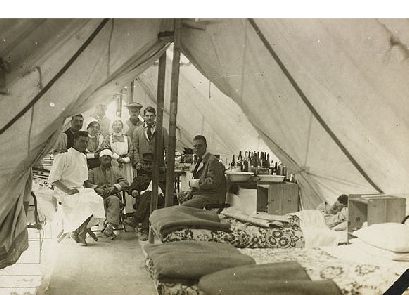

On 18 March 1916 whilst on duty Edwin Francis fell and injured his left ankle. It

was clearly a bad fall because he was taken to No. 2 Canadian General Hospital at

Le Treport, a few miles north of Dieppe, where he was diagnosed with a fractured

tibia. Le Treport was an important medical centre during the War, and the Canadian

hospital was one of two hospitals, although by the end of the war the number had

increased. In 1916, the Canadian Hospital was a combination of huts and medical tents

situated next to the British  General Hospital which had take over the town’s grand

Trianon Hotel. Here, Edwin’s leg was set in a splint before he was shipped home on

27 March. After a long, uncomfortable journey by ambulance, train and boat, he a

General Hospital which had take over the town’s grand

Trianon Hotel. Here, Edwin’s leg was set in a splint before he was shipped home on

27 March. After a long, uncomfortable journey by ambulance, train and boat, he a rrived

in Blighty to find himself on the familiar turf of London, at the Military Hospital

in Endell Street in Covent Garden. It was a stark contrast to the mud and horror

of the trenches he had left behind.

rrived

in Blighty to find himself on the familiar turf of London, at the Military Hospital

in Endell Street in Covent Garden. It was a stark contrast to the mud and horror

of the trenches he had left behind.

Back in Blighty

One of the most remarkable hospitals of the war, the Endell Street Hospital had been

established in a former Workhouse in 1916 under the control of Dr Flora Murray and

Dr Louisa Garrett Anderson, the daughter of Elizab eth Garrett Anderson. Many of the

women doctors who had volunteered were active suffragettes determined to prove that

they were as capable as their male counterparts. It was the first hospital for men

run entirely by women and its motto was ‘Deeds not Words’ — an appropriate mantra

not only for its approach to healthcare but also for its campaign for universal suffrage.

After initial scepticism, the hospital attracted great praise from the medical profession;

Edwin must have counted himself lucky to receive such expert care.

eth Garrett Anderson. Many of the

women doctors who had volunteered were active suffragettes determined to prove that

they were as capable as their male counterparts. It was the first hospital for men

run entirely by women and its motto was ‘Deeds not Words’ — an appropriate mantra

not only for its approach to healthcare but also for its campaign for universal suffrage.

After initial scepticism, the hospital attracted great praise from the medical profession;

Edwin must have counted himself lucky to receive such expert care.

Edwin was in hospital for almost three months, finally being discharged on 23 June

1916. He was given a ten-

After spending time with his family, at 5 o’clock on the morning of Tuesday 4 July

1916, Edwin boarded a train and travelled to Winchester to rejoin his Battalion.

Whilst he had been home recuperating, across the channel the Allies had started ‘the

Big Push’, a large-

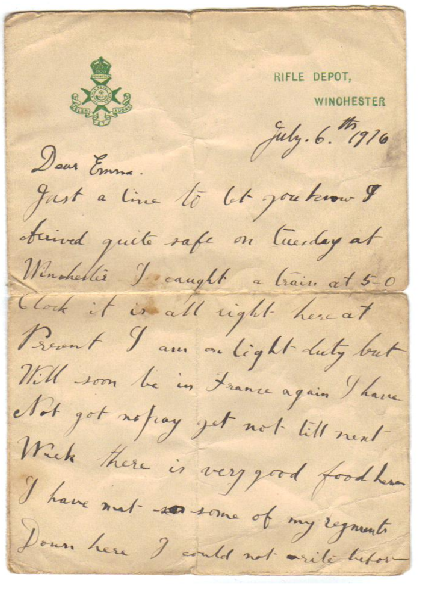

Dear Emma

Just a line to let you know I arrived quite safe on Tuesday at Winchester I caught a train at 5 o’clock. It is all right here at present. I am on light duty but will soon be in France again. I have not got no pay yet, not till next week. There is very good food here. I have met some of my regiment down here. I could not rite before. Is all at present. Give my love to the children and this is my best love for you from your loving husband, E Bostock. xxxxxxxxx

Send me a line and let me know if you get this Emma. xxxxxxxx

Despite an expectation that he would be sent back to France, a couple of months later,

on 22 September, Edwin Francis was posted to Sheerness, perhaps to the reservist

Battalion of the King’s Royal Rifle Corp which was stationed there as part of the

home defence guar ding Britain’s ports and waterways. Perhaps his wound had not healed

sufficiently, or Emma had written to him that she was expecting another child, although

the biggest surprise was still in store. Edwin continued his duties in Sheerness,

but it was not long before his injury flared up and on 27 October he was admitted

to hospital with an ulcerated leg. Two weeks later, on 11 November, he was transferred

to Lees Court. Given the terrible loss of life and the appauling conditions on the

Western front, it was a blessing.

ding Britain’s ports and waterways. Perhaps his wound had not healed

sufficiently, or Emma had written to him that she was expecting another child, although

the biggest surprise was still in store. Edwin continued his duties in Sheerness,

but it was not long before his injury flared up and on 27 October he was admitted

to hospital with an ulcerated leg. Two weeks later, on 11 November, he was transferred

to Lees Court. Given the terrible loss of life and the appauling conditions on the

Western front, it was a blessing.

Lees Court (pictured on the right) is a grand country house and estate at Sheldwich

near Faversham, deep in the Kent countryside. During the War it was used as a convalescent

home mainly for Canadian soldiers. Edwin remained in these grand surroundings for

a month and by the end of 1916 had spent about a quarter of the year in different

hospitals. As a result of his injuries, he was declared  unfit for active service

and on 20 January 1917 was transferred to the 29th Middlesex Regiment, a Works Battalion.

unfit for active service

and on 20 January 1917 was transferred to the 29th Middlesex Regiment, a Works Battalion.

By now Emma had broken the news to him that she was expecting twins; almost nine months to the day since Edwin had returned to Winchester from his Summer furlough, while the war raged across the Channel, Emma waged her own private battle, giving birth to two healthy boys, Arthur Henry and William Albert, on 1 March 1917.

On 15 May 1917, Edwin was transferred to the 39th Company, a labour corps. It was with this Company, stationed for sometime in Shoreham by Sea that he saw out the war. Not long before Armistice Day, in September 1918, he went absent for two days, forfeiting two days’ pay. He was finally demobbed at Crystal Palace in January 1919, although he continued to be a reserve on mobilisation. In 1920, like all soldiers who had served overseas during the war, he was awarded a Victory Medal (an example is shown on the left).

Peace time

After the war, Edwin tried to acclimatise and adjust to civilian life, but found

it difficult to settle down to the quiet and patient industry of cabinet making after

the horror of the trenches, the excitement of foreign shores, and the grandeur of

country estates. His daughter, May, recalled that her father drank and was often

abusive to his wife. Perhaps his old wounds pained him or, like many service men,

he was suffering from post-

Drinking was a socially accepted part of working class culture and only frowned

upon when it became excessive; what little social time people had was often passed

in the local public house which was often warmer and more comfortable than a person’s

home; it also offered company and an few hours escape from the harsh realities of

life, and as well as drinking, people gathered to talk, sing, dance and play pub

games. As well as being socially acceptable, Edwin had a history of excessive drinking

in the family: his sister, Esther, was a whisky drinker who died in 1931 aged 54,

and his grandfather, George Bostock, had died at a young age of cirrhosis. Alcoholism

can be hereditary and is certainly influenced by social behaviours and conditioning,

so perhaps when life got too difficult for Edwin, his natural tendency was to drown

his sorrows. In an age when the public house was a focal point for working-

Sometime between 1935 and 1939, Edwin walked out on Emily and his children. He didn’t

go far; the 1939 Electoral Roll shows him living at Palace Road in Hackney and by

1945 he was at 1 Balcorne Street, just off Well Street, Hackney. In 1954, he had

moved to number 7 and was living with his niece and her husband. Around Christmas

1961 he suffered a heart attack while out in Well Street and was taken to Bethnal

Green Hospital where he died on New Year’s Eve. Unlike his grandfather and his sister

who had died relatively young of drink-

who’s related to whom

james bostock

(circa 1770)

edwin francis bostock

(1878-

emma peters

m

living moss

(born 1947)

living moss

(born 1968)

may alexandra bostock

(1911-

| paternal tree |

| maternal tree |

| index of names |

| monger photos |

| moss photos |

| collins photos |

| bostock photos |

| george moss |

| william moss |

| george c moss |

| eleanor evans |

| gregory family |

| thomas gregory |

| thomas gregory |

| sissey family |

| christopher sissey |

| sissey children |

| brisco family |

| william briscoe |

| john biscoe |

| susan webb |

| briscoe children |

| betsy biscoe |

| james bostock |

| george bostock |

| james g bostock |

| edwin f bostock |

| may bostock |

| marie wicks & sarah homan |

| homan bostock family |

| steward family |

| charles steward |

| ducro family |

| esther steward |

| mary & ann steward |

| stephen ducro |

| mary ducro |

| Ann_Briggs |

| hockerday family |

| thomas hockaday |

| mary ann hockerday |

| peters family |

| william peters |

| joseph peters |

| emily a peters |

| joseph collins |

| samuel collins |

| joseph collins |

| henry j collins |

| florence a collins |

| william shepherd |

| ann e shepherd |

| rogers family |

| john rogers |

| sarah a rogers |

| harvey family |

| thomas harvey |

| ann harvey |

| grigg family |

| william monger |

| charles monger |

| george monger |

| albert j monger |

| benham family |

| thomas benham |

| mary a benham |

| stephen dunford |

| fanny dunford |

| cawte family |

| robert cawte |

| william cawte |

| john r cawte |

| reynolds family |

| william reynolds |

| emma reynolds |