florence ada collins (1906-

Early years

Florence Ada Collins was born on 27 February  1906 at 30 Derwent Street in Greenwich.

The daughter of Henry Joseph Collins and Sarah Ann Rogers, her arrival was not heralded

as a momentous event, as her mother had given birth to at least ten children previously.

As a result, life for the young Ada was noisy and boisterous, but there was always

someone to talk to or play with, usually in the street, although which street changed

frequently. Ada later recalled that she would go to sleep in one house and wake up

in another. Like many working class families, moves did not take place until at least

10 o’clock at night. The family’s few household effects, including the prized feather

mattress, were loaded onto a wheelbarrow rented from the local greengrocer and the

children, half asleep, would walk or be carried to their new home.

1906 at 30 Derwent Street in Greenwich.

The daughter of Henry Joseph Collins and Sarah Ann Rogers, her arrival was not heralded

as a momentous event, as her mother had given birth to at least ten children previously.

As a result, life for the young Ada was noisy and boisterous, but there was always

someone to talk to or play with, usually in the street, although which street changed

frequently. Ada later recalled that she would go to sleep in one house and wake up

in another. Like many working class families, moves did not take place until at least

10 o’clock at night. The family’s few household effects, including the prized feather

mattress, were loaded onto a wheelbarrow rented from the local greengrocer and the

children, half asleep, would walk or be carried to their new home.

After a rudimentary education, Ada left school at fourteen and started work, although

long before this, she had earned money through various part-

A family of her own

By 1926, Ada and her family had moved to Livingstone Road near Clapham Junction.

The house was a large three- Among the guests were Ada’s elder

sister, Kit and her husband, and Albert’s sister, Edith Wyatt and her husband. Five

months later in August 1926, Ada and Albert’s son, Albert (‘Bert’), was born. Over

the next ten years, six more children followed: Ruth (‘Sis’) (September 1927), Lilian

Jeanee (October 1928), John Henry George (‘Jack’) (May 1930), Edith Margaret (‘Peg’)

(1931), James (‘Jim’) (1932), and Ivy Christine (‘Chris’) (1936).

Among the guests were Ada’s elder

sister, Kit and her husband, and Albert’s sister, Edith Wyatt and her husband. Five

months later in August 1926, Ada and Albert’s son, Albert (‘Bert’), was born. Over

the next ten years, six more children followed: Ruth (‘Sis’) (September 1927), Lilian

Jeanee (October 1928), John Henry George (‘Jack’) (May 1930), Edith Margaret (‘Peg’)

(1931), James (‘Jim’) (1932), and Ivy Christine (‘Chris’) (1936).

The 1930s were difficult years for many families. Finances were stretched and the

family lived from week to week, juggling what little money they had: Albert’s suit

would go to the pawn shop on Monday and be taken out on Friday or Saturday ready

for the weekend. But however little money there was to go around, Ada always made

sure her children were clean and smartly dressed, even if the clothes from the tally

man and the three eldest girls wore matching outfits because it was cheaper to buy

them that way. And there was always time to enjoy life; day trips to the seaside,

trips to the local fair on Clapham Common, or a bottle of stout and a sing-

Ask Ada . . .

With families living in close proximity and cramped conditions, life spilled out onto the street and the front door was always open. Ada’s was a welcoming house and relatives, friends and neighbours often popped by for a chat. Ada was not just a willing listener but was ready with practical help and advice. One day a neighbour came to see Ada explaining that her fiance was home on leave and her engagement ring and his suit were in the pawnbrokers; she only had half a crown – not enough to redeem both items and did not know what to do. Ada told her to change the half a crown into pennies, feed them in the gas meter and stick her head in the oven. After they’d laughed about the young lady’s predicament, no doubt Ada reminded her neighbour that her fiance would be so glad to be home and see his sweetheart that he wouldn’t mind.

Ada’s other talent was for getting things done. She ran savings clubs for various activities and events: trips to the seaside, the street party for the Coronation in 1953, and the ‘Perm club’. The latter enabled friends and neighbours to put money aside to save up to have their hair permanently waved. Ada collected their money, keeping a record of how much everyone had paid and on what date their perm was due. She would then put all of the weeks of the year in a box and girls considered themselves lucky if they drew out a week just before an important day such as Christmas or Easter.

It is clear from these recollections that Ada was a capable and practical woman who was well regarded and trusted by her neighbours; she always came up with the money even if on one occasion, one lady sat at the hair dressers for two hours waiting for Ada to pay the hairdresser before he would begin. Presumably there was a frantic dash to the pawn shop to raise some cash.

The day war broke out

On 3 September 1939 at 9 o’clock in the morning, an ultimatum was presented in Berlin

giving Hilter until 11 o’clock to undertake to withdraw his troops from Poland. At

11.15am Chamberlain addressed the nation, stating “no such undertaking has been received

and that consequently this country is at war with Germany”.  With seven young children

and a husband of thirty-

With seven young children

and a husband of thirty-

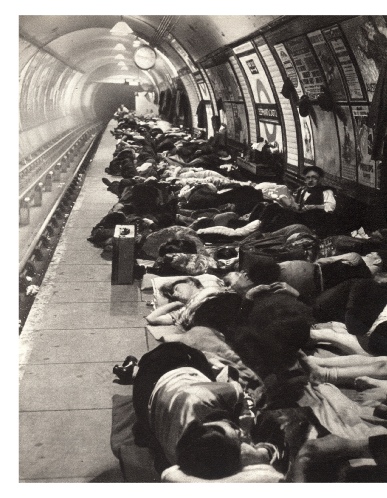

Air raid warnings began in London on the first day of the war, but the first real threat came in August 1940. In a bid for air supremacy, Germany attempted to destroy all areas of strategic importance: Clapham Junction was an obvious target and bombing raids were frequent. The children, apart from Bert who had left school that summer, were evacuated along with millions of other children (the photograph on the right shows children being evacuated). Ada was forced to take refuge in the Andersen shelter in the back yard or in the nearby Underground station (the photograph below shows people sleeping on the platform of Piccadilly underground station). As well as the sleepless nights and the disruption, Ada had to contend with the chaos caused by damage to gas, electricity and water supplies, and transport, and rationing.

One of the worst nights of the Blitz came just before New Year 1941. Bombing on the

night of 29 December 1940 was particularly heavy and several bombs fell in the area.

By the time the war came to an end in 1945, little was left of Livingstone Road and

the surrounding roads. Ada’s daughter, Ruth, recalled one incident. Peg, Jim and

Chris had been evacuated and only Ada, Ruth, Lilian and Jackie were at home. It was

a Sunday morning and Ada had sent Jackie to get tea and sugar while the girls laid

the table and helped prepare breakfast. The air raid siren sounded. The family had

lived through many false alarms and Ada thought this might be another one. However,

their dog, a shaggy sheepdog, was agitated and Ada decided they should go to the

shelter. It was a make shift shelter in the garden without a door. Bert had painted

it to make it more inviting and written the words ’welcome’ above the doorway. Once

in the shelter, Lilian remembered she had left her bag in the house and ran back

to get it. As she returned,  Ada just managed to drag her into the shelter and place

a piece of wood over the open doorway before the bomb exploded. They sat in the shelter

while buildings fell around them and the sirens wailed. As they emerged into an atmosphere

of smoke and dust Ada’s first thought was to make sure that her neighbours were all

right. They were, but the houses had suffered terrible damage: the floors had disappeared

and part of the stair treads were missing. In fact, the structure was so precarious

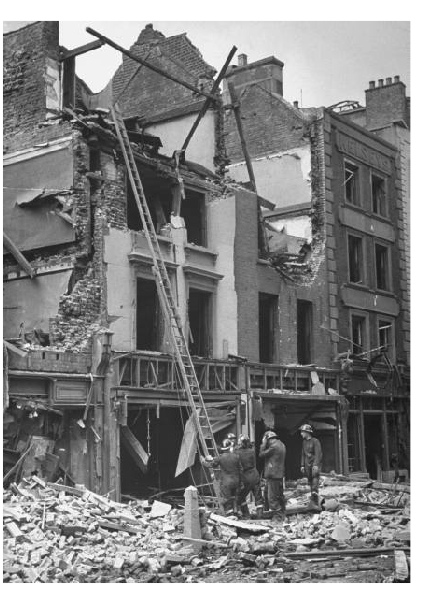

they could not enter the house even to collect a few personal effects. The photograph

on the left shows a house damaged by bombing being surveyed by the heavy rescue squad

in 1940.

Ada just managed to drag her into the shelter and place

a piece of wood over the open doorway before the bomb exploded. They sat in the shelter

while buildings fell around them and the sirens wailed. As they emerged into an atmosphere

of smoke and dust Ada’s first thought was to make sure that her neighbours were all

right. They were, but the houses had suffered terrible damage: the floors had disappeared

and part of the stair treads were missing. In fact, the structure was so precarious

they could not enter the house even to collect a few personal effects. The photograph

on the left shows a house damaged by bombing being surveyed by the heavy rescue squad

in 1940.

The war caused havoc with every day life: Albert, along with most of the male population between the ages of 14 and 64, was enlisted to help with the war effort, Bert was on active service abroad and the children were evacuated to Reading. Air raids continued through August and September 1940 and into 1941, and periodically after that. The last, and perhaps most frightening, experience to face Londoners came in June 1944 with the V1 and V2 rockets. The engines of these rockets, or ‘doodlebugs’ as they were called, cut out before they exploded; Ruth and Lilian recounted that the moments between the engine cutting out and the explosion were worse than anything, as they sat waiting, unable to predict where the bomb would fall.

There was great rejoicing throughout Britain and in the Collins’ household when Germany signed a document of surrender on 8 May 1945. Ada gave thanks for the safe return of her husband and her son and the deliverance of her family, and no doubt they gave thanks for her: she had provided for them, comforted them, held them together and, with her strength of character and confidence, had made them believe they would pull through. (The photograph on the left shows the VE Day celebrations in London.)

A return to normality

Although the war had ended, rationing of food and clothes continued; 100,000 houses had been destroyed and many more damaged, and the streets were filled with derelict houses and bomb craters. This meant plenty of work for Albert who had returned to his old employment as a builder, and life quickly settled back to normal until the summer of 1946. At the age of forty, Ada was surprised to find that she was pregnant. The nagging fear in her mind was that, because of her age, her baby might not be healthy, so she and Albert were relieved when, on 6 March 1947, Ada gave birth to a healthy baby girl, whom they named Brenda Patricia.

There was no money for holidays to e scape war-

scape war-

Working days were long and often hard; lunch was eaten in the fields and consisted

of sandwiches made that morning, wrapped in newspaper to stop the sticky, bitter

resin of the hops transferring from one’s hands to one’s sandwiches; there were long

walks to the village to buy provisions for dinner and cooking took place over an

open fire. But in a good year, when the hops were plentiful, workers could earn a

decent wage. Hopping had other advantages: being out in the clean, unpolluted air;

the camaraderie between workers as they moved from row to row of the hops; and sing-

Pastures new

In February 1952, Ada and her family were given the opportunity to leave London permanently,

as part of the Councils initiative to rehouse families and provide a decent standard

of housing. They were re- ewed clothes, and made sure there was

something tasty to eat, such as bacon puddings (which were steamed in a tea cloth

resulting in the puddings turning out with the pattern of the tea cloth). Finances

were easier too and there was money for holidays to the seaside and Butlins holiday

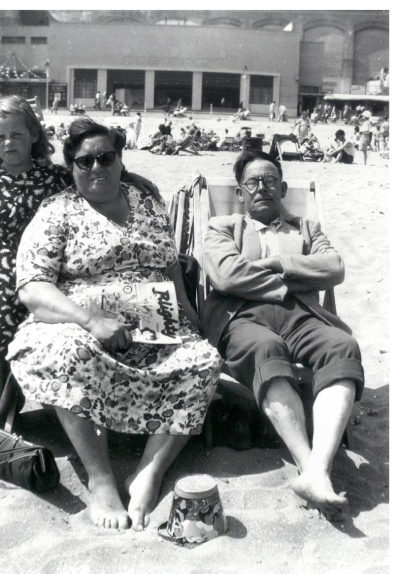

camp. The photograph on the left shows Brenad, Ada and Albert at Ramsgate in the

early 1950s.

ewed clothes, and made sure there was

something tasty to eat, such as bacon puddings (which were steamed in a tea cloth

resulting in the puddings turning out with the pattern of the tea cloth). Finances

were easier too and there was money for holidays to the seaside and Butlins holiday

camp. The photograph on the left shows Brenad, Ada and Albert at Ramsgate in the

early 1950s.

Although all of her children, apart from Brenda, had left home, the family would get together, particularly for Christmas when the house was always full. The piano lid would be raised and there would be lots of merry making late into the evening, by which time the children were tucked into Ada and Albert’s bed head to toe and the adults made do with whatever space they could find on the floor.

In the late 1950s, while living at Radstock Way, Ada was diagnosed with diabetes. She had to have insulin injections every day but, as with everything else, took it in her stride. With all her children, except Brenda, having left home, and the number of her grandchildren expanding, life was easier than ever before. However, Ada’s failing health meant she was unable to get out as much as in the past and one wonders if she missed the hustle and bustle of London. Her family were devastated when, on 3 December 1963, she died of a heart attack at the age of 57. She was cremated at the Surrey & Sussex Crematorium near Crawley in Sussex.

who’s related to whom

lilian jeanne monger

(1928-

living fenley

(born 1946)

living moss

(born 1968)

samuel collins

(1834-

florence ada collins

(1906-

m

| paternal tree |

| maternal tree |

| index of names |

| monger photos |

| moss photos |

| collins photos |

| bostock photos |

| george moss |

| william moss |

| george c moss |

| eleanor evans |

| gregory family |

| thomas gregory |

| thomas gregory |

| sissey family |

| christopher sissey |

| sissey children |

| brisco family |

| william briscoe |

| john biscoe |

| susan webb |

| briscoe children |

| betsy biscoe |

| james bostock |

| george bostock |

| james g bostock |

| edwin f bostock |

| may bostock |

| marie wicks & sarah homan |

| homan bostock family |

| steward family |

| charles steward |

| ducro family |

| esther steward |

| mary & ann steward |

| stephen ducro |

| mary ducro |

| Ann_Briggs |

| hockerday family |

| thomas hockaday |

| mary ann hockerday |

| peters family |

| william peters |

| joseph peters |

| emily a peters |

| joseph collins |

| samuel collins |

| joseph collins |

| henry j collins |

| florence a collins |

| william shepherd |

| ann e shepherd |

| rogers family |

| john rogers |

| sarah a rogers |

| harvey family |

| thomas harvey |

| ann harvey |

| grigg family |

| william monger |

| charles monger |

| george monger |

| albert j monger |

| benham family |

| thomas benham |

| mary a benham |

| stephen dunford |

| fanny dunford |

| cawte family |

| robert cawte |

| william cawte |

| john r cawte |

| reynolds family |

| william reynolds |

| emma reynolds |