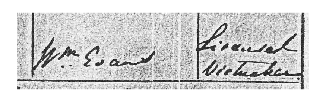

On 24 June 1799, William Evans married Eleanor Hughes at the Church of St George

the Martyr near Borough High Street in Southwark. Instead of the usual ‘X’, he made

his mark in the marriage register with a ‘W’. The register shows that William was

a widower, but when and where he was born, or how long he had been married previously,

is unknown. Two years later, he and Eleanor returned to St George’s where their daughter,

Eleanor, was baptised.

A year later, in about 1803, William moved his family a few miles east to Deptford.

The year is significant. Britain had been at war with France from 1793 until 1802,

when peace was declared. It proved to be rather tenuous and on 18 May 1803, King

George III declared a breakdown in the peace: after less than fourteen months, Britain

was back at war with her old adversary. War can stimulate growth and industry as

effectively as prosperity, and William and his family settled in King Street alongside

the Royal Dockyard and the Victualling Yard in Deptford.

A year later, in about 1803, William moved his family a few miles east to Deptford.

The year is significant. Britain had been at war with France from 1793 until 1802,

when peace was declared. It proved to be rather tenuous and on 18 May 1803, King

George III declared a breakdown in the peace: after less than fourteen months, Britain

was back at war with her old adversary. War can stimulate growth and industry as

effectively as prosperity, and William and his family settled in King Street alongside

the Royal Dockyard and the Victualling Yard in Deptford.

Supply and demand

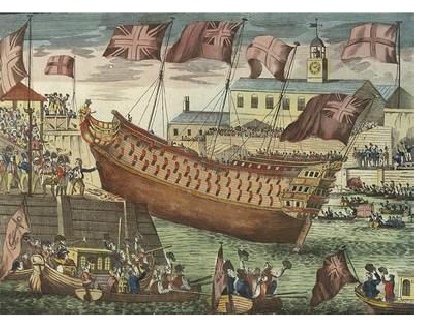

The Dockyard had been founded in 1513 by Henry VIII. By the eighteenth century, due

to the silting of the Thames, its use was restricted to ship building and the distribution

of stores to other yards and fleets abroad. Even so, it was one of the most complete

repositories for naval stores in Europe. It covered more than thirty acres of ground,

and contained every convenience for building, repairing, and fitting out ships-of-the-line,

“those floating bulwarks for which England is, or rather was, renowned, and which

carry a hundred and twenty guns and a thousand men to guard her shores from the invader,

or to bear her fame with her victories to the remotest seas of the ocean”.  The illustration

above shows the dockyard in about 1780-1800. It held food, rum, tobacco, bedding,

clothing, medicine and included abbatoirs, pickling houses, brewing houses, ship

biscuits’ works, a cooperage, a rum distillery and a mill. Such was its size that

it provided supplies for the navy’s other victualling yards at Gosport and Plymouth.

The illustration

above shows the dockyard in about 1780-1800. It held food, rum, tobacco, bedding,

clothing, medicine and included abbatoirs, pickling houses, brewing houses, ship

biscuits’ works, a cooperage, a rum distillery and a mill. Such was its size that

it provided supplies for the navy’s other victualling yards at Gosport and Plymouth.

King Street was situated just out of view on the left-hand side of the painting and

is marked on the map on the left. It was here that a second, daughter, Margaret,

was born in the Summer of 1804. The baptism records William’s occupation using the

general term of ‘labourer’ but he almost certainly worked at the dockyard, along

with over a thousand other people living in the vicinity.

During this period, the area was a hive of activity, both on and off shore, and William

and his family were well-placed to hear news as soon as it arrived. It may have been

whilst the family were at King Street that, on 6 November 1805, news arrived of Britain’s

victory over the French fleet at the battle of Trafalgar and of the death of Admiral

Lord Nelson. The Times newspaper captured the mood of the nation when it wrote, ‘We

do not know whether we should mourn or rejoice. The country has gained the most splendid

and decisive Victory that has ever graced the naval annals of England; but it has

been dearly purchased. The great and gallant NELSON is no more’. Nelson’s body lay

in state at the nearby Greenwich Hospital and William Evans may well have been one

of the 100,000 or so people who filed past to pay their last respects.

Amongst the hubbub and other momentous events, life carried on in much the same way

for William. A few months after Nelson’s funeral flotilla sailed up the River Thames,

a third daughter was born, Elizabeth. She was baptised at the Church of St Nicholas,

by which time, the family had moved to Hughes Fields, a few streets away. By 1808,

they were once again within a stone’s throw of the Dockyard, living at New Row, a

row of cottages built in the eighteenth century, presumably for shipbuilders and

other artisans. The photograph on the right shows New Row a century or so later,

although it would have looked much the same when William lived here. The houses provided

a decent standard of living and sufficient space for a growing family, and it was

here that William’s first son, William, was born in September.

A growing family

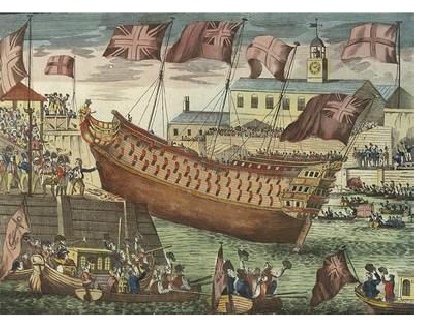

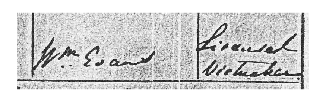

During these years when Britain was at war, William continued to work as a labourer,

the humdrum of life punctuated with births and events of national importance, such

as the launching of HMS Charlotte on 17 July 1810 from Deptford’s dockyard.  The illustration

on the left event captures something of the excitement of the event, which drew a

crowd of about 20,000 people. Not long after, Eleanor gave birth to another son,

David. Another daughter, Mary Ann, arrived in 1813 while the family were living at

Broomfield Place. In nine years, the family had lived in at least four properties,

all within a few minutes walk of the dockyards; the war had been good for business,

at least for William and his family.

The illustration

on the left event captures something of the excitement of the event, which drew a

crowd of about 20,000 people. Not long after, Eleanor gave birth to another son,

David. Another daughter, Mary Ann, arrived in 1813 while the family were living at

Broomfield Place. In nine years, the family had lived in at least four properties,

all within a few minutes walk of the dockyards; the war had been good for business,

at least for William and his family.

The Napoleonic War finally ended in June 1815 with Napoleon’s defeat at the Battle

of Waterloo. Its end marked the start of the Dockyard’s demise; from 1821 only maintenance

work was carried out there, and by 1830, it was used only for ship breaking. In contrast,

William’s fortunes appear to have risen. When his daughter, Eleanor married in 1839,

she gave her father’s occupation as a ‘licensed victualler’.  In the nineteenth century,

as well as referring to publicans, the term also covered people who sold alcohol

and food, and beer retailers, and indicates that some time between 1813 and 1839,

William purchased a licence to retail alcohol. Working at the victualling yard for

a decade had clearly paid off, providing William with expertise, connections and

a regular income, some of which he may have been able to save.

In the nineteenth century,

as well as referring to publicans, the term also covered people who sold alcohol

and food, and beer retailers, and indicates that some time between 1813 and 1839,

William purchased a licence to retail alcohol. Working at the victualling yard for

a decade had clearly paid off, providing William with expertise, connections and

a regular income, some of which he may have been able to save.

Unfortunately, no further information has been discovered about William, including

details of his death, the commonness of his name making research difficult.

A year later, in about 1803, William moved his family a few miles east to Deptford.

The year is significant. Britain had been at war with France from 1793 until 1802,

when peace was declared. It proved to be rather tenuous and on 18 May 1803, King

George III declared a breakdown in the peace: after less than fourteen months, Britain

was back at war with her old adversary. War can stimulate growth and industry as

effectively as prosperity, and William and his family settled in King Street alongside

the Royal Dockyard and the Victualling Yard in Deptford.

A year later, in about 1803, William moved his family a few miles east to Deptford.

The year is significant. Britain had been at war with France from 1793 until 1802,

when peace was declared. It proved to be rather tenuous and on 18 May 1803, King

George III declared a breakdown in the peace: after less than fourteen months, Britain

was back at war with her old adversary. War can stimulate growth and industry as

effectively as prosperity, and William and his family settled in King Street alongside

the Royal Dockyard and the Victualling Yard in Deptford.  The illustration

above shows the dockyard in about 1780-

The illustration

above shows the dockyard in about 1780-

The illustration

on the left event captures something of the excitement of the event, which drew a

crowd of about 20,000 people. Not long after, Eleanor gave birth to another son,

David. Another daughter, Mary Ann, arrived in 1813 while the family were living at

Broomfield Place. In nine years, the family had lived in at least four properties,

all within a few minutes walk of the dockyards; the war had been good for business,

at least for William and his family.

The illustration

on the left event captures something of the excitement of the event, which drew a

crowd of about 20,000 people. Not long after, Eleanor gave birth to another son,

David. Another daughter, Mary Ann, arrived in 1813 while the family were living at

Broomfield Place. In nine years, the family had lived in at least four properties,

all within a few minutes walk of the dockyards; the war had been good for business,

at least for William and his family.  In the nineteenth century,

as well as referring to publicans, the term also covered people who sold alcohol

and food, and beer retailers, and indicates that some time between 1813 and 1839,

William purchased a licence to retail alcohol. Working at the victualling yard for

a decade had clearly paid off, providing William with expertise, connections and

a regular income, some of which he may have been able to save.

In the nineteenth century,

as well as referring to publicans, the term also covered people who sold alcohol

and food, and beer retailers, and indicates that some time between 1813 and 1839,

William purchased a licence to retail alcohol. Working at the victualling yard for

a decade had clearly paid off, providing William with expertise, connections and

a regular income, some of which he may have been able to save.