Juggernauts of the river

One of the best description that exists of the Thames lighterman in the nineteenth

century was recorded by Henry Mayhew in London Labour and the London Poor. Mayhew

spoke to hundreds of Londoners of various character, backgrounds and occupations

and recorded his findings and the conversations he had. His essays not only provide

details of the various occupations of London’s residents but, more importantly, their

living conditions and incomes, their hopes and aspirations.

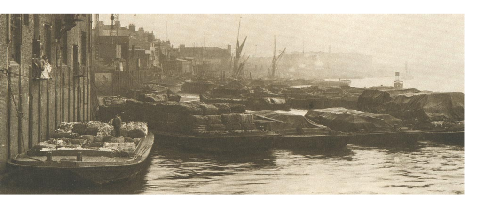

The lighterman transported cargo from vessels in the river to docks or the shore

and was a distinct class from the waterman who could only convey passengers. The

boats in which the goods were transported were known as ‘lighters’ or ‘barges‘ (a

larger lighter mainly used for transporting coal). These vessels were used to transport

corn, timber, stone, groceries and general merchandise and could carry between 6

and 120 tons.

The lighterman transported cargo from vessels in the river to docks or the shore

and was a distinct class from the waterman who could only convey passengers. The

boats in which the goods were transported were known as ‘lighters’ or ‘barges‘ (a

larger lighter mainly used for transporting coal). These vessels were used to transport

corn, timber, stone, groceries and general merchandise and could carry between 6

and 120 tons.

The average size and price of a lighter was 14 tons and £120. Some men owned their

own lighters and were generally a prosperous group; other lightermen obtained work

by being ‘on the look out’. They might offer their services to the captain of a vessel

to bring his cargo ashore, or to a merchant or grocer who needed their goods transported.

Laden lighters were worked by at least two men; they had no engine or sail and relied

on the tide, being steered by a long oar. It was common, therefore, for lighters

to be moored in the middle of the river, waiting the turn of the tide.  When unladen,

lighters were moored alongshore, often close to a waterman’s stairs.

When unladen,

lighters were moored alongshore, often close to a waterman’s stairs.

Many lightermen, especially ‘master-lighterman’, employed a number of hands on a

regular basis. Even the average lighterman was an occasional employer; engaging watermen

to assist in loading or unloading or hiring a lighter in addition to their own.

A lighterman employed ‘casually’ could expect to earn six shillings a day, whereas

the regular employee earned between 25 and 30 shillings a week, with extra for night

work. Mayhew estimated that there were about 1,225 lighterman on the river, driving

at least 1,100 lighters, and four or five hundred bargemen, driving around 200 barges

(not including coal barges which were owned by the coal-merchants who had wharves).

Mayhew reported that the lightermen generally had better homes than the watermen,

due to their higher salaries and were a sober class of men; they all lived near the

river, generally on the Middlesex side.

Serving time

All lightermen were licensed by the City of London as freemen of the ‘Company of

Master, Wardens, and Commonalty of Watermen and Lighterman’, to work their vessels

in all parts of the river from New Windsor to Yantlet Creek (below Gravesend), and

in all docks, canals, creeks and harbours of the river Thames.

Up to the early 20th century, nearly all apprentices served a seven year apprenticeship.

An apprentice would be taken to Waterman’s Hall by a fully licensed lighterman and

there be ‘bound’ as an unlicensed apprentice. After two years, during which time

he learnt to “move safely and quickly along the narrow gun'les of the Thames barges,

how to row craft up and down the various reaches, how to cope with wind and tide,

the geography of London Port, its docks and locks, its bridges and wharves, its traffic

and its temperament. And a thousand and one things beside”, he would return to Waterman’s

Hall for his examination for his ‘twos’, before he became a licensed apprentice.

Five more years of learning his craft until he knew the river like the back of his

hand, until it was time to present himself at Waterman’s Hall for the third time.

“I ceased to be ‘bound’, I became a journeyman, I was given my ‘freedom’ and the

ancient title that went with it. I became a Freeman of the River Thames”.

Who you know

It was a tough and often dangerous life. But there was also a great sense of camaraderie

and comradeship amongst lightermen, unsurprising given that it was a close-knit society

where sons were apprenticed to fathers and often married into families of other lightermen.

Above all, there was an immense sense of pride and belonging. A lighterman recalls

his first drive after his apprenticeship:

“One could never forget the first drive under oars, rowing under oars is called driving,

and on the first drive, from a boy one suddenly becomes a man.”

With the changing face of trade, new forms of transport, and the greater mechanisation

of the docks, the trade of the lighterman declined and by the 1970s it ceased to

be a ‘living’ trade, instead became confined to the pages of history books. The only

passing remembrance we have today of a trade once vital to the wealth of London is

Doggett's Coat and Badge. This is the prize and name for the oldest continuously

held sporting contest in the world. Instigated by Thomas Doggett in 1715 to mark

George I’s accession to the throne, and held every year since, up to six watermen

race the 4 miles 5 furlongs between “The Swan” pub at London Bridge and “The Swan”

pub at Chelsea, for this prestigious honour. The winner's prize is a traditional

watermen's red coat with a silver badge added, displaying the horse of the House

of Hanover and the word ‘Liberty’, in honour of George I’s accession to the throne.

Recollections taken from ‘Men of the Tideway’ by Dick Fagan and Eric Burgess

The lighterman transported cargo from vessels in the river to docks or the shore

and was a distinct class from the waterman who could only convey passengers. The

boats in which the goods were transported were known as ‘lighters’ or ‘barges‘ (a

larger lighter mainly used for transporting coal). These vessels were used to transport

corn, timber, stone, groceries and general merchandise and could carry between 6

and 120 tons.

The lighterman transported cargo from vessels in the river to docks or the shore

and was a distinct class from the waterman who could only convey passengers. The

boats in which the goods were transported were known as ‘lighters’ or ‘barges‘ (a

larger lighter mainly used for transporting coal). These vessels were used to transport

corn, timber, stone, groceries and general merchandise and could carry between 6

and 120 tons.  When unladen,

lighters were moored alongshore, often close to a waterman’s stairs.

When unladen,

lighters were moored alongshore, often close to a waterman’s stairs.