Today, London must rank as one of the most multi-cultural cities in the word. But

this is not a new phenomenon. Britain’s trading heritage, and a generally tolerant

attitude has made it a melting pot of cultures for centuries. Amongst the first waves

of immigrants (after the Romans in the 1st century AD and the Normans in 1066) were

the Huguenots, and is estimated that one in four Londoners has Huguenot ancestry.

Today, London must rank as one of the most multi-cultural cities in the word. But

this is not a new phenomenon. Britain’s trading heritage, and a generally tolerant

attitude has made it a melting pot of cultures for centuries. Amongst the first waves

of immigrants (after the Romans in the 1st century AD and the Normans in 1066) were

the Huguenots, and is estimated that one in four Londoners has Huguenot ancestry.

Huguenots were French protestants who for many years enjoyed peace and prosperity

in France. From about 1580, they came under continual harassment by the Roman Catholics

and in 1685, King Louis XIV not only outlawed the practise of Protestantism but stripped

Huguenots of their civil rights. This meant they were unable to inherit property,

their marriages were invalidated resulting in their children being declared illegitimate

and they had to bury their dead in secret. As a result, around 200,000 fled France

to seek a new life.

It is estimated that around 50,000 settled in England, mainly in the Soho and Spitalfields

areas of London. By settling outside the bounds of the City of London, they hoped

to avoid the restrictive legislation of the City Guilds. Also, Spitalfields, which

had been the site of England’s largest medieval hospital (the name Spitalfields is

a contraction of ‘hospital fields’) had become a textile center — first for laundresses,

then for calico dyeing, then, in the eighteenth century, silk weaving. A general

anti-Catholic sentiment, and stories of French atrocities against Protestants, ensured

the Huguenot immigrants a warmer welcome than was usually given to foreigners.

Spitalfields’ silk weavers

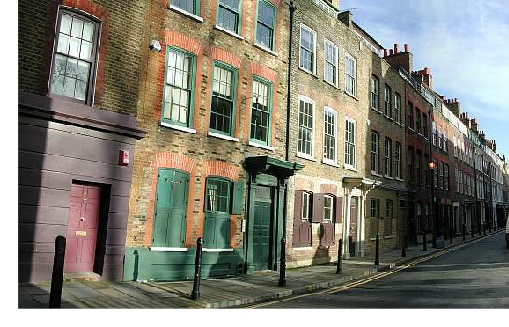

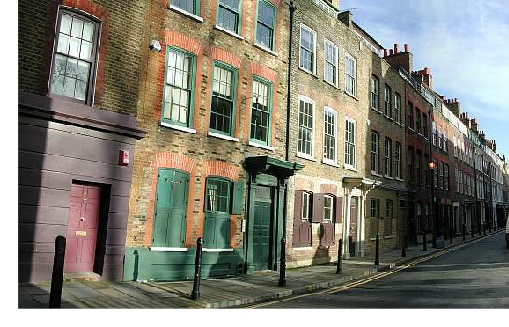

Many of the Huguenots who settled in Spitalfields came from Lyons, the centre of

the French silk industry. They set up business as silk weavers, using handlooms to

weave raw silk imported from Italy. They also brought with them a newly invented

technique which allowed them to give thin silk taffeta a glossy lustre. Their skills,

combined with their strong Calvinist belief in the virtues of hard wo rk, thrift and

self-discipline, meant that many of them prospered, building large and handsome houses

around Brick Lane, with glass-ceilinged workshops in the attics, where they set up

their weaving looms. At the height of its prosperity, Spitalfields had 12,000 looms

and was one of the greatest weaving centres of Europe.

rk, thrift and

self-discipline, meant that many of them prospered, building large and handsome houses

around Brick Lane, with glass-ceilinged workshops in the attics, where they set up

their weaving looms. At the height of its prosperity, Spitalfields had 12,000 looms

and was one of the greatest weaving centres of Europe.

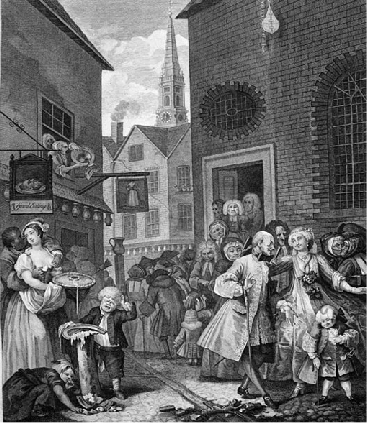

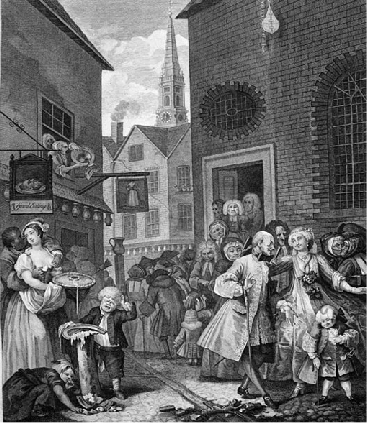

The industry benefited from various pieces of legislation which sought to protect

it, initially by placing high import duties on foreign silk from France and India

and then banning their import. Some of this legislation came about after silk weavers

rioted in the streets and the masters’ houses were broken into and property and looms

destroyed; women wearing Indian calico were also attacked in the streets.

At first the Huguenots kept their own distinct identity; they spoke French and founded

their own churches so that by the early eighteenth century there were nine Huguenot

churches in London, prompting the building of Christ Church in 1729. The concentration

of French speaking immigrants in a well defined community ensured not only the survival

of their language, but also their fashion and customs, giving rise to a distinctive

culture and identity which lasted for several generations. As well as their distinctive

houses—tall and narrow with roof garrets for looms and large windows to let in as

much light as possible for weaving — the silk weavers were known for their love

of song birds and flowers and many houses had back gardens and window boxes filled

with flowers.

In the eighteenth century, Soho was described as “abounding with French so that it

is an easy matter for a stranger to imagine himself in France”. Of course, there

were the inevitable complaints about their unfamiliar diet, and hostility on occasion,

often motivated by fears that the French were depriving Londoners of work. but on

the whole, the Huguenot community acquired a certain respectability.

Over time, however, the Huguenots assimilated into English society. There was a drift

towards the Anglican Church, and names were anglicized — Ferret became Ferry, and

Fouache became Fash — often due to mistakes made by English clerks; Ducros sometimes

appears as Ducrow.

By the 1820s, after the repeal of long-standing embargoes on imported textiles, the

English textile industry collapsed and France once again dominated the field. It

is estimated that, in 1831, half of the 100,000 residents of Spitalfields district

depended on the weaving industry for their livelihood. After the silk-weaving industry

failed, the area declined and eventually became a centre for furniture building,

boot-making and later, tailoring. In late Victorian times it became seedier still,

and was infamous for murders by Jack the Ripper.

Today, London must rank as one of the most multi-

Today, London must rank as one of the most multi- rk, thrift and

self-

rk, thrift and

self-