Early years

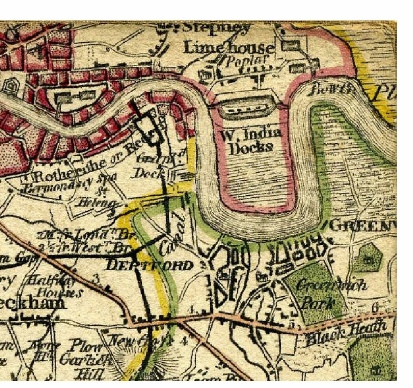

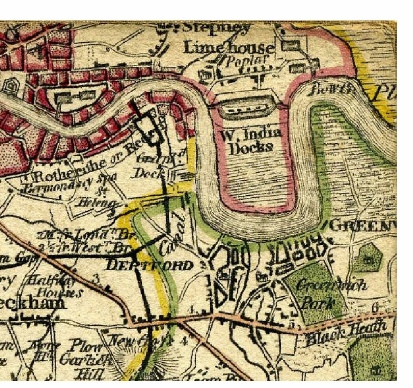

The history of the Moss family begins with father and son, William and George — two

names that flow through the Moss line. George was born in Deptford in about 1809,

the son of William Moss. Deptford stretches south from the River Thames and when

George was born it  was a bustling area of industry and trade, and central to Britain

in her war against France (apart from a brief respite in 1802/3, Britain had been

at war with France since 1793). Closest to the river, the emphasis was on victualling

and shipbuilding: wharves, warehouses, chemical works, soap and candle factories,

sawmills, paintworks, coal and timber wharves, breweries, glue works, gasworks, tar

distilleries, and manufacturers of artificial manure stretched along a narrow strip

of the river filling the air with the sounds and smells of industry. Further south,

life was a little quieter; Deptford High Street (or Butt Lane as it was called) was

emerging from its rural past with a farm occupying much of the west side.

was a bustling area of industry and trade, and central to Britain

in her war against France (apart from a brief respite in 1802/3, Britain had been

at war with France since 1793). Closest to the river, the emphasis was on victualling

and shipbuilding: wharves, warehouses, chemical works, soap and candle factories,

sawmills, paintworks, coal and timber wharves, breweries, glue works, gasworks, tar

distilleries, and manufacturers of artificial manure stretched along a narrow strip

of the river filling the air with the sounds and smells of industry. Further south,

life was a little quieter; Deptford High Street (or Butt Lane as it was called) was

emerging from its rural past with a farm occupying much of the west side.

Nothing is known about George’s parents other than that, in 1839, his father was

working as a bricklayer. Although the work was seasonal, there should have been no

shortage of work: between 1801 and 1851 the population of London almost tripled as

people migrated to the capital from the surrounding counties; large estates were

built, gradually joining what had hitherto been separate villages into one urban

sprawl, and by 1815 London was the largest city in the world.

George should not have wanted for the necessities of life, although in the early

1800s this would not have included a formal education. In 1816 only about half of

the children in Britain attended school or learnt to read and write; in 1835 the

average duration of school attendance was just one year. For working class families,

formal schooling for a child who would learn a practical trade or work in unskilled

employment was not only unaffordable but also thought to be unnecessary.

An honest wage

It was common for sons to take up their father’s profession, but bricklaying was

physically demanding and seasonal. Perhaps George was not suited for it or his family

believed he could do better by another trade, so in the early 1820s he took up tailoring.

He may have been formally apprenticed to a master tailor, his parents paying a fee

and signing the legal agreement which apprenticed him for between five and seven

years, or he may simply have worked for a tailor for several years, during which

time he would have been trained and may have been provided with board and lodgings

by his master. The painting on the right shows the interior of a tailor’s shop in

the late eighteenth century; the apprentices and tailors sit cross-legged on the

workbench threading needles and sewing, and with the open fire and their mugs of

ale the scene looks rather homely. Whatever form George’s training took, by about

1830 he was free to ply his trade independently. In official documents, he styled

himself as a ‘journeyman tailor’ (journeyman derives from the French journee, meaning

a day and signified that a person was paid by the day not that they travelled around).

Gaining his freedom also meant that he was in a position to marry.

It was common for sons to take up their father’s profession, but bricklaying was

physically demanding and seasonal. Perhaps George was not suited for it or his family

believed he could do better by another trade, so in the early 1820s he took up tailoring.

He may have been formally apprenticed to a master tailor, his parents paying a fee

and signing the legal agreement which apprenticed him for between five and seven

years, or he may simply have worked for a tailor for several years, during which

time he would have been trained and may have been provided with board and lodgings

by his master. The painting on the right shows the interior of a tailor’s shop in

the late eighteenth century; the apprentices and tailors sit cross-legged on the

workbench threading needles and sewing, and with the open fire and their mugs of

ale the scene looks rather homely. Whatever form George’s training took, by about

1830 he was free to ply his trade independently. In official documents, he styled

himself as a ‘journeyman tailor’ (journeyman derives from the French journee, meaning

a day and signified that a person was paid by the day not that they travelled around).

Gaining his freedom also meant that he was in a position to marry.

Eleanor Evans and family life

By 1836, George had met Eleanor Evans, the daughter of William Evans, a licensed

victualler, and a local girl. In an era when many women did not have a formal profession,

Eleanor was a tailoress, so it is likely George met her at their place of work or

through his employer. Their son was born on 30 June 1837 whilst George and Eleanor

were living above one of the shops that lined the Broadway, the bustling thoroughfare

in Deptford. The illustration on the left shows the street at about the same time,

although it would have been busy with carts and horses, street traders, and people

taking fowl and livestock to market. A month later, George and Eleanor baptised their

son at the Church of St Paul; as was customary, they named him George after his father.

The 1841 census (taken on 6 June) records two other children in the household: Eleanor

Moss in about 1831 and Emma Moss born around 1833. No baptism records have been found

for Eleanor and Emma. They may have been George’s children, as George would have

completed his apprenticeship in about 1831, or they may have been Eleanor’s children

from a previous relationship.

By 1836, George had met Eleanor Evans, the daughter of William Evans, a licensed

victualler, and a local girl. In an era when many women did not have a formal profession,

Eleanor was a tailoress, so it is likely George met her at their place of work or

through his employer. Their son was born on 30 June 1837 whilst George and Eleanor

were living above one of the shops that lined the Broadway, the bustling thoroughfare

in Deptford. The illustration on the left shows the street at about the same time,

although it would have been busy with carts and horses, street traders, and people

taking fowl and livestock to market. A month later, George and Eleanor baptised their

son at the Church of St Paul; as was customary, they named him George after his father.

The 1841 census (taken on 6 June) records two other children in the household: Eleanor

Moss in about 1831 and Emma Moss born around 1833. No baptism records have been found

for Eleanor and Emma. They may have been George’s children, as George would have

completed his apprenticeship in about 1831, or they may have been Eleanor’s children

from a previous relationship.

Even after their son’s birth, George and Eleanor were in no hurry to marry. It was

not until two years later on 13 October 1839 that they made their way from Cannon

Street, a few streets south of the B roadway and a little off the main thoroughfare,

to the Church of St Paul to be married. The church is one of the finest baroque churches

in England and even today is an impressive and imposing landmark with its elegant

steeple and semi-circular portico approached by a flight of stone steps. One wonders

how George and Eleanor felt as they passed between the elegant Tuscan columns and

stood before the altar with the figures of Saints Michael and Gabriel gazing down

at them from the Venetian stained-glass windows.

roadway and a little off the main thoroughfare,

to the Church of St Paul to be married. The church is one of the finest baroque churches

in England and even today is an impressive and imposing landmark with its elegant

steeple and semi-circular portico approached by a flight of stone steps. One wonders

how George and Eleanor felt as they passed between the elegant Tuscan columns and

stood before the altar with the figures of Saints Michael and Gabriel gazing down

at them from the Venetian stained-glass windows.

By 1839 they had been living together for at least three (and perhaps almost ten),

were of full age and single. Why did they wait so long? One explanation is that they

had decided to leave Deptford and move to Essex. It would have been a significant

move for both of them, but particularly for Eleanor who had been born and raised

in Deptford and whose family still lived close by. Marriage would have given her

respectability and afforded her some security away from her family. Whatever the

reasons, by the Spring of 1841 George and his family had crossed two rivers: the

River Thames that divides London into north and south, and the River Lea that marks

the East-West boundary between Middlesex and Essex.

Crossing the river

George and his family settled in Stratford in Essex. Stratford, meaning a narrow

ford, grew up at a place where the River Lea could be crossed. Because of its position

on the old Roman road from London into Essex, it became a coaching stop for travellers.

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, industrial activities grew up along

its banks including silk weaving, calico printing, the manufacture of  Bow porcelain,

and distilling. The rest of the area was made up of small agricultural hamlets and

the large houses of city merchants, although by the late eighteenth century many

of these had ceased to exist as wealthy merchants moved to more fashionable parts

of London and the suburbs.

Bow porcelain,

and distilling. The rest of the area was made up of small agricultural hamlets and

the large houses of city merchants, although by the late eighteenth century many

of these had ceased to exist as wealthy merchants moved to more fashionable parts

of London and the suburbs.

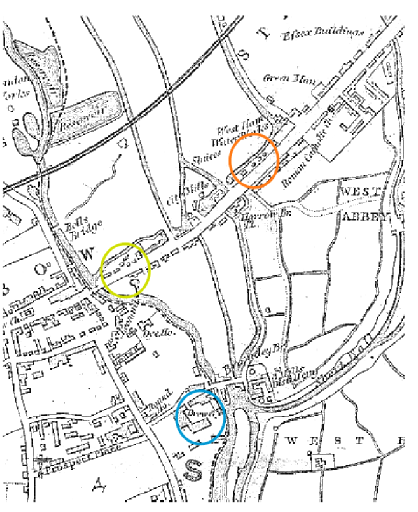

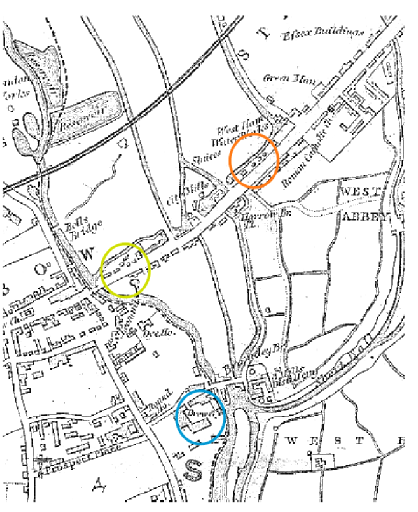

In 1840, the area east of Bow Common was still little more than a group of large

villages; the engraving on the right shows Stratford High Street in about 1840, looking

not dissimilar to the painting of the Broadway in Deptford. But unlike Deptford whose

fortunes had peaked, the area east of the River Lea grew was growing rapidly and

it may have been for this reason that George and Eleanor chose to settle there. Given

the proximity of Stratford to Deptford — at least as the crow flies — they may have

crossed the Thames by boat and made their way north through the Isle of Dogs, or

perhaps they crossed the ‘new’ London Bridge, whose construction they had most likely

witnessed a decade earlier. They went first to Waterworks Row, a small terraced house

near the waterworks (shown in orange on the map below). Not long after, Eleanor gave

birth to a daughter, Rosetta. The following year George moved his family to Brewers

Row (possibly located in blue on the map). It was here that their daughter, Emma,

died in June 1842 of inflammation of the lungs; she was eight years old. Her death

certificate records that ‘Ellen Moss, daughter of Robert Moss, a tailor, died on

22 June 1842’ and that the information was provided by a Sarah Rose of 2 Brewers

Row. T he following day, the certificate was corrected in the presence of Eleanor

Moss to read ‘Emma Moss, daughter of George Moss, a tailor’. With such mistakes,

it is no wonder that researching family history can confound even the most experienced

genealogists.

he following day, the certificate was corrected in the presence of Eleanor

Moss to read ‘Emma Moss, daughter of George Moss, a tailor’. With such mistakes,

it is no wonder that researching family history can confound even the most experienced

genealogists.

The following year Eleanor gave birth to a son, named William after his grandfathers,

and in 1845 to another daughter, named Eliza. Both William and Eliza were born in

China Row (shown in green), close to the Bow Bridge. That the family had lived in

three descriptively named Rows was no co-incidence. These rows of terraced housing

generally fronted the industries they described, offering low-cost housing, albeit

often badly built. Whilst it was not uncommon for families to move regularly, since

most families rented rather than owned their properties, it does suggest that finances

were difficult for the Moss household.

George continued to work as a tailor and is listed in White’s Essex Directory of

1848. He was one of 26 tailors working in West Ham and was based on the High Street

where he probably rented a small workshop. Whilst the Victorian era was an age of

growth and prosperity for many, mechanisation and advances in technology also brought

great hardship, and from the mid-1840s the conditions for many working-class people

deteriorated. Employers began to employ women and girls to carry out work that had

traditionally been undertaken by men, and men and women were forced to work for less

or be unemployed. A journeyman tailor speaking to Thomas Mayhew, the great chronicler

of life in mid-nineteenth century London, noted:

“Before the year 1844 I could live comfortably, and keep my wife and children (I

had five in my family) by my own labour. My wife then attended to her domestic and

family duties; but since that time owing to the reduction in prices, she has been

compelled to resort to her needle, as well as myself, for her living. My wife’s earnings

are, upon an average, 8s per week. She makes dresses. I never would teach her to

make waistcoats, because I knew the introduction of female hands had been the ruin

of my trade. With the labour of myself and wife now I can only earn 32s a week, and

six years ago I could make 36s. If I had a daughter I should be obliged to make her

work as well, and then probably, with the labour of the three of us, we could make

up at the week’s end as much money, as, up to 1844, I could get by my own single

hands.”

This account is born out by the fact that Eleanor had also taken up her needle to

help supplement the family’s income. By doing so, George and Eleanor managed to make

ends meet, but life was difficult and in March 1851 the family was sharing what was

most likely a modest terraced house at 1 James’ Place in Stratford with another family.

Ten years later when the 1861 census was taken on 7 April, Eleanor was described

as a ‘tailor’s widow’. George’s death has not been traced and he departs this history,

at least in terms of the documentary evidence, as discreetly as he entered it.

was a bustling area of industry and trade, and central to Britain

in her war against France (apart from a brief respite in 1802/3, Britain had been

at war with France since 1793). Closest to the river, the emphasis was on victualling

and shipbuilding: wharves, warehouses, chemical works, soap and candle factories,

sawmills, paintworks, coal and timber wharves, breweries, glue works, gasworks, tar

distilleries, and manufacturers of artificial manure stretched along a narrow strip

of the river filling the air with the sounds and smells of industry. Further south,

life was a little quieter; Deptford High Street (or Butt Lane as it was called) was

emerging from its rural past with a farm occupying much of the west side.

was a bustling area of industry and trade, and central to Britain

in her war against France (apart from a brief respite in 1802/3, Britain had been

at war with France since 1793). Closest to the river, the emphasis was on victualling

and shipbuilding: wharves, warehouses, chemical works, soap and candle factories,

sawmills, paintworks, coal and timber wharves, breweries, glue works, gasworks, tar

distilleries, and manufacturers of artificial manure stretched along a narrow strip

of the river filling the air with the sounds and smells of industry. Further south,

life was a little quieter; Deptford High Street (or Butt Lane as it was called) was

emerging from its rural past with a farm occupying much of the west side.

It was common for sons to take up their father’s profession, but bricklaying was

physically demanding and seasonal. Perhaps George was not suited for it or his family

believed he could do better by another trade, so in the early 1820s he took up tailoring.

He may have been formally apprenticed to a master tailor, his parents paying a fee

and signing the legal agreement which apprenticed him for between five and seven

years, or he may simply have worked for a tailor for several years, during which

time he would have been trained and may have been provided with board and lodgings

by his master. The painting on the right shows the interior of a tailor’s shop in

the late eighteenth century; the apprentices and tailors sit cross-

It was common for sons to take up their father’s profession, but bricklaying was

physically demanding and seasonal. Perhaps George was not suited for it or his family

believed he could do better by another trade, so in the early 1820s he took up tailoring.

He may have been formally apprenticed to a master tailor, his parents paying a fee

and signing the legal agreement which apprenticed him for between five and seven

years, or he may simply have worked for a tailor for several years, during which

time he would have been trained and may have been provided with board and lodgings

by his master. The painting on the right shows the interior of a tailor’s shop in

the late eighteenth century; the apprentices and tailors sit cross- By 1836, George had met Eleanor Evans, the daughter of William Evans, a licensed

victualler, and a local girl. In an era when many women did not have a formal profession,

Eleanor was a tailoress, so it is likely George met her at their place of work or

through his employer. Their son was born on 30 June 1837 whilst George and Eleanor

were living above one of the shops that lined the Broadway, the bustling thoroughfare

in Deptford. The illustration on the left shows the street at about the same time,

although it would have been busy with carts and horses, street traders, and people

taking fowl and livestock to market. A month later, George and Eleanor baptised their

son at the Church of St Paul; as was customary, they named him George after his father.

The 1841 census (taken on 6 June) records two other children in the household: Eleanor

Moss in about 1831 and Emma Moss born around 1833. No baptism records have been found

for Eleanor and Emma. They may have been George’s children, as George would have

completed his apprenticeship in about 1831, or they may have been Eleanor’s children

from a previous relationship.

By 1836, George had met Eleanor Evans, the daughter of William Evans, a licensed

victualler, and a local girl. In an era when many women did not have a formal profession,

Eleanor was a tailoress, so it is likely George met her at their place of work or

through his employer. Their son was born on 30 June 1837 whilst George and Eleanor

were living above one of the shops that lined the Broadway, the bustling thoroughfare

in Deptford. The illustration on the left shows the street at about the same time,

although it would have been busy with carts and horses, street traders, and people

taking fowl and livestock to market. A month later, George and Eleanor baptised their

son at the Church of St Paul; as was customary, they named him George after his father.

The 1841 census (taken on 6 June) records two other children in the household: Eleanor

Moss in about 1831 and Emma Moss born around 1833. No baptism records have been found

for Eleanor and Emma. They may have been George’s children, as George would have

completed his apprenticeship in about 1831, or they may have been Eleanor’s children

from a previous relationship.  roadway and a little off the main thoroughfare,

to the Church of St Paul to be married. The church is one of the finest baroque churches

in England and even today is an impressive and imposing landmark with its elegant

steeple and semi-

roadway and a little off the main thoroughfare,

to the Church of St Paul to be married. The church is one of the finest baroque churches

in England and even today is an impressive and imposing landmark with its elegant

steeple and semi- Bow porcelain,

and distilling. The rest of the area was made up of small agricultural hamlets and

the large houses of city merchants, although by the late eighteenth century many

of these had ceased to exist as wealthy merchants moved to more fashionable parts

of London and the suburbs.

Bow porcelain,

and distilling. The rest of the area was made up of small agricultural hamlets and

the large houses of city merchants, although by the late eighteenth century many

of these had ceased to exist as wealthy merchants moved to more fashionable parts

of London and the suburbs.  he following day, the certificate was corrected in the presence of Eleanor

Moss to read ‘Emma Moss, daughter of George Moss, a tailor’. With such mistakes,

it is no wonder that researching family history can confound even the most experienced

genealogists.

he following day, the certificate was corrected in the presence of Eleanor

Moss to read ‘Emma Moss, daughter of George Moss, a tailor’. With such mistakes,

it is no wonder that researching family history can confound even the most experienced

genealogists.